arts@sfbg.com

FILM The results of the wee election that happened a couple weeks ago were generally a good thing, needless to say, but just as light also causes shadow, so the light bulb that went off for a majority of voters cast into deeper darkness a certain minority. Oh, you’ve heard the wailings and lamentations: the death of “traditional” America (read: white people, “they” are coming to take your women and steal your home entertainment center), brutal new taxations designed to funnel your hard-earned money to whole communities of professional freeloaders, the national anthem to be translated into Communist (it’s a language, like speaking in demonic tongues), etc.

Some patriots, no longer loving it, are leaving it — mostly to inexpensive warmer retirement magnets whose natives aren’t too uppity yet to avoid calling you “Sir” or “Boss.” Others are planning to secede, one state at a time. (Yes, definitely including the ones you were already hoping would somehow cut ties. Can they take Fox News with them?) Mentally and politically, they seceded a while ago. But now it is on — Elvis is leaving the building, because he didn’t get his way so fuck y’all.

What’s bad about this is that, as with any psychotic break, bystanders may suffer for not sharing or getting in the way of the sufferer’s particular symptoms — in this case likely to primarily consist of depression, violent outbursts, substance abuse, weapons stockpiling, paranoid delusions, paranoid delusions, and reckless home schooling. How many basement man caves have been fertilizing plans for what we might term “assassination,” “domestic terrorism” or “going postal” since November 6, imaging personal heroism and national salvation their eventual reward? It’s like a significant section of the populace has turned into our crazy uncle, off his meds, muttering apocalyptically in the corner and sure to remember where we live sooner or later.

So it is with mixed emotions, to say the least, that one greets the alarmingly timely arrival of Red Dawn. A remake of a 1984 movie that seemed a pretty nutty ideological throwback even during the Reagan Era’s revived Cold War air conditioning (and even alongside such crazy Satan-is-Soviet competition as 1985’s Rambo: First Blood Part II and Rocky IV), it is a movie that should have come out a couple years ago, having been shot late 2009. But in the meantime MGM was undergoing yet another seismic financial rupture, and as the film sat around for lack of the means needed for distribution and marketing, it occurred that perhaps it already had a fatal, internal flaw. You see, this update re-cast our invaders from Russkies to People’s Republicans, tapping into the modern fear of China as debtor and international bully. But: China is also a huge fledgling market for Hollywood product, despite censorship, import quotas, and whatnot. China heard about Red Dawn and was not happy, endangering the foreign profit margins for future MGM product.

So a tortured makeover of the remake ensued; scenes were added, re-shot, and digitally altered to impose a drastic narrative change. China now goes unmentioned, replaced as villain by the country which is nobody’s film market, even if that choice is so absurd it gets acknowledged as such by dialogue: “North Korea? It doesn’t make any sense!” someone says here. It’s a query that goes unanswered.

Yup, in the new Red Dawn a coastal Washington state burg — mom, apple pie and flag figuring large in the opening montage — is the first attack point in a wholesale invasion of the U.S. (pop. 315 million) by the Democratic People’s Republic (pop. 25 million). It’s football season, so a Spokane suburb’s team — Wolverines!! — lends its name as battle cry and its revved up healthy young flesh as guerilla martyrs to the fight for, ohm yeah, freedom. Do they drink beer? Do they rescue cheerleader girlfriends from concentration camps? Do they kick North Korean ass? Do you really need to ask?

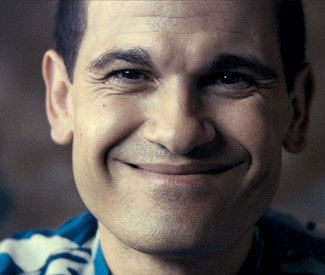

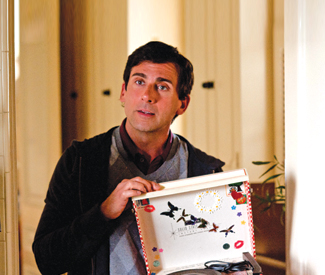

Of course this Red Dawn is ridiculous, though as a pulp action fantasy it’s actually fairly entertainingly well-crafted by veteran stunt coordinator-second unit director Dan Bradley. The actors maintain straight faces with variable degrees of success — on the upside pre-Thor Chris Hemsworth, (whose other 2009-shot MGM film The Cabin in the Woods also got released this year) as ex-Marine alpha male, on the downside an irksome Josh Peck as his little bro and an inexplicable Connor Cruise as a teammate. The adopted son of a certain really famous Scientologist, the latter surely got this role on merit alone; otherwise we’d be forced to believe he made up in nepotism what he amply lacks in looks, voice, and presence.

So what does this silly movie have to do with the election, you ask? Just this: its production travails mean this rah-rah, just-credibly-gritty-enough (but still mostly video-game-like) tale of fighting the power has arrived just in time to become a training manual (or at least recruitment video) for revolutionist reactionary rednecks. It’s ready-made for an audience so deprived of air, irony, and other key elements to reality that they’re probably in a hundred or more basements right now, plotting the overthrow of our Socialist Islamophilic oligarchy.

RED DAWN opens Wed/21 in Bay Area theaters.