cheryl@sfbg.com

FALL ARTS Autumn is primo movie season, not just in awards-hungry Hollywood. Here in the Bay Area we’ve got unique rep programming and festivals galore to keep our eyeballs fully engaged — and just enough room for some prestige movie-star pictures for dessert.

REP VENUES

Standing its ground on turbulent, tech-chic Valencia Street, gallery and screening venue Artists’ Television Access marks its 30th anniversary with “ATA Lives!” Sept. 4 brings a showcase of works by staffers past and present — and then a 30-hour marathon screening and benefit curated by local artist Gilbert Guerrero. Other anniversary events include programs dedicated to the Kuchar brothers and a fresh installment in “live cinema” series Mission Eye & Ear. www.atasite.org

ATA co-founder Craig Baldwin launches the latest Other Cinema season Sept. 13 with an “ATA Superstars” showcase of works by Bryan Boyce, James Hong, and others. Another highlight is Sept. 20’s “Anomalies from the Archive,” with East Coast artists Walter Forsberg and John Klacsmann performing what Baldwin describes as their “exploded view of a Technicolor lab error,” as well as sharing “kino-curiosities” from the Prelinger Archives, SF Media Archive, and other sources. Also cool: a basketball-themed night (Oct. 25) and an experimental sci-fi program (Nov. 8) that takes on the failed Soviet lunar landing, among other topics. www.othercinema.com

The Exploratorium continues its “Saturday Cinema” shorts (Sept. 6, it features 1933 stop-motion marvel The Mascot) as well as its “Off the Screen” series, including another chance to see Forsberg and Klacsmann’s Technicolor N.G. (Sept. 18) and an outdoor showing of Impossible Light — maybe your only chance to see a doc about the Bay Lights while the Bay Lights themselves glitter in the background (Sept. 25). www.exploratorium.edu

Now in its 11th year, Bernal Heights Outdoor Cinema continues its tradition of showing works by local artists. It kicks off Sept. 4 at El Rio with a shorts program, plus a performance by comedian Johnny Steele; it continues the next night with the ever-popular “Film Crawl on Cortland,” with screenings at venues like the Bernal Heights Neighborhood Center throughout the night. Sept. 6, “Under the Stars” brings short films to Precita Park. Oct. 7, the fest returns for a “Best of Bernal Night” at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts. http://bhoutdoorcine.org

The San Francisco Cinematheque‘s fall calendar includes more Kuchar love, with Anthology Film Archives’ Andrew Lampert at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts to celebrate his new George Kuchar Reader (Oct. 18). And! At the Castro, two nights of “Mary Woronov, Warhol Superstar,” with Woronov in person alongside screenings of 1966’s Chelsea Girls and Hedy (Nov. 6-7). www.sfcinematheque.org

Also at the Castro, the San Francisco Silent Film Festival moves its popular “Silent Winter” to Sept. 20 and renames it (aha!) “Silent Autumn.” Per usual, the programming is excellent, with top-notch musical accompaniment planned for each screening. Compilations include “Another Fine Mess: Silent Laurel and Hardy Shorts” and the British Film Institute’s time-capsule peek at the start of World War I, “A Night at the Cinema in 1914.” Features are the Valentino classic The Son of the Sheik (1926); Buster Keaton comedy The General (1926); and German Expressionist chiller The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1920). www.silentfilm.org

The Castro Theatre’s own programming unveils tributes to both Robin Williams (series starts Sept. 7) and Lauren Bacall (Oct. 1). The Castro is also the most consistent venue for Jesse Hawthorne Ficks’ “Midnites for Maniacs” series; Sept. 19 honors “Diegetic Odysseys” with a double-feature of Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) and Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980). www.castrotheatre.com; www.midnitesformaniacs.com

Fall at the Pacific Film Archive includes complete retrospectives “Eyes Wide: The Films of Stanley Kubrick” (Sept. 4-Oct. 31) and “James Dean, Restored Classics from Warner Bros” (Sept. 5-20). There’s also the Berkeley-appropriate “Activate Yourself: The Free Speech Movement at 50” (Sept. 11-Oct. 30); movie-geek catnip “Jean-Luc Godard: Expect Everything from Cinema” (Sept. 12-Oct. 23) and “Life: The Films of Hou Hsaio-hsien” (Oct. 10-Dec. 14); and the launch of an impressively depthed overview of Georgian cinema (Sept. 26-April 19). www.bampfa.berkeley.edu

Didn’t make it to any of the big out-of-town film festivals this past year? Don’t worry — the Roxie‘s got your back with a calendar that includes the buzzed-about Memphis (opens Sept. 19); Nick Cave docudrama 20,000 Days on Earth (Sept. 26); Catherine Breillat’s Abuse of Weakness (Oct. 3); and Alex Ross Perry’s Listen Up Philip (Oct. 26). www.roxie.com

Over at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, film/video curator Joel Shepard promises an action-packed fall, with series like the extremely timely “Lest We Forget: Remembering Radical San Francisco” (Oct. 2-26); Halloween-time new horror films from Spain, including Albert Serra’s Casanova-meets-Dracula tale Story of My Death (2013); “New Black Cinema” (Nov. 6-9) and “New Waves in Mexican Cinema” (Dec. 4-21); and Double Play, a new documentary on Richard Linklater that’s screening as part of a Linklater-James Benning dual focus (Nov. 13-16). www.ybca.org

The San Francisco Film Society begins its fall mini-festival season Nov 6. with “French Cinema Now,” followed by “Hong Kong Cinema” (Nov. 14-16) and “New Italian Cinema” (Nov. 19-23). It also presents a screening of acclaimed indie Hellion, with director Kat Candler in person (Sept. 15), and hosts Ethiopian American filmmakers Zeresenay Mehari and Mehret Mandefro as its latest artists-in-residence (Oct. 1-14). www.sffs.org

And in micro-cinema news, the Vortex Room promises “Rock You Like a Vortex Room” as its next Thursday Night Film Cult theme (starts Oct. 8; think musical-themed oddities, like 1974’s Phantom of the Paradise), while the Berkeley Underground Film Society’s “Lost and Out of Print” September event majors in burlesque, highlighted by a 16mm screening of 1930’s The Blue Angel (Sept. 19-21). Facebook: The Vortex Room; lostandoutofprintfilms.blogspot.com

FEELING FESTIVE?

California Independent Film Festival Lifetime achievement award winner Julie Newmar appears in person at this fest, which also includes a 30th anniversary tribute to Sixteen Candles. Sept. 11-14; www.caiff.org

Legacy Film Festival on Aging Shorts, features, and documentaries from around the world that take on “the challenges and triumphs of aging.” Sept. 12-14; www.legacyfilmfestivalonaging.org

World’s Independent Film Festival Formerly billed as the Third World Indie Film Festival, this Silicon Valley-based event presents films by emerging international filmmakers. Sept. 19-21, www.theworldindiefilmfest.com

San Francisco Irish Film Festival Contemporary Irish cinema, including shorts and Irish-language films (with English subtitles). Sept. 18-20; http://sfirishfilm.com

Cine+Mas SF’s San Francisco Latino Film Festival Features, docs, and shorts from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Puerto Rico, Peru, Uruguay, and points beyond. Sept. 19-27; www.sflatinofilmfestival.com

Oakland Underground Film Festival This East Bay celebration of indie cinema kicks off with SXSW sci-fi hit The Infinite Man and the Michael Jai White-starring Falcon Rising. Sept. 25-28; www.oakuff.org

Iranian Film Festival This fest’s motto is “discovering the next generation of Iranian filmmakers.” Sept. 27-28; www.iranianfilmfestival.org

Arab Film Festival Emphasizes independent films that provide “insightful and innovative perspectives” on Arab people, culture, history, and politics. This year, look for an emphasis on comedy, animation, and films for kids. Oct./Nov. TBD; www.arabfilmfestival.org

Mill Valley Film Festival History doesn’t lie: Five of the last six Best Picture winners had their Bay Area debuts at this veteran fest, which is also known for its star-studded special events. Oct. 2-12; www.mvff.org

“Berlin and Beyond Autumn Showcase” The actual B&B fest isn’t until January 2015, but fans of German-language cinema can nibble on this mini-fest, which showcases a 35mm screening of the late Michael Glawogger’s 1998 Megacities. Oct. 11; www.berlinbeyond.com

ReelAbilities Bay Area Disabilities Film Festival Presented by Creative Growth, this fest promotes the awareness and appreciation of the lives, stories, and art of people with disabilities. Oct. 15-19; www.creativegrowth.org

United Nations Association Film Festival The all-documentary festival highlights themes of human rights, the environment, refugee issues, war and peace, and more. This year’s theme is “Bridging the Gap.” Oct. 16-26; www.unaff.org

American Indian Film Festival Now in its 39th year, this fest showcases works (including narratives, docs, music videos, and animation) by and about North American Indian and Canada First Nation people. Nov. 1-9; www.aifisf.com

San Francisco Dance Film Festival Shorts, documentaries, and performance films celebrating dance, with a special tribute to documentarian Frederick Wiseman. Nov. 6-9; www.sfdancefilmfest.org

San Francisco Transgender Film Festival This extremely popular fest (program info coming in early October) celebrates films that challenge stereotypes and “promote the visibility of transgender and gender variant people.” Nov. 7-9; www.sftff.org

3rd I San Francisco International South Asian Film Festival: Bollywood and Beyond This year’s fest focuses on music and dance, with a centerpiece lecture-performance on “Bollywood maestros” R.D. Burman and A.R. Rahman. Nov. 6-9 and 15; www.thirdi.org

FIRST-RUN INTRIGUE

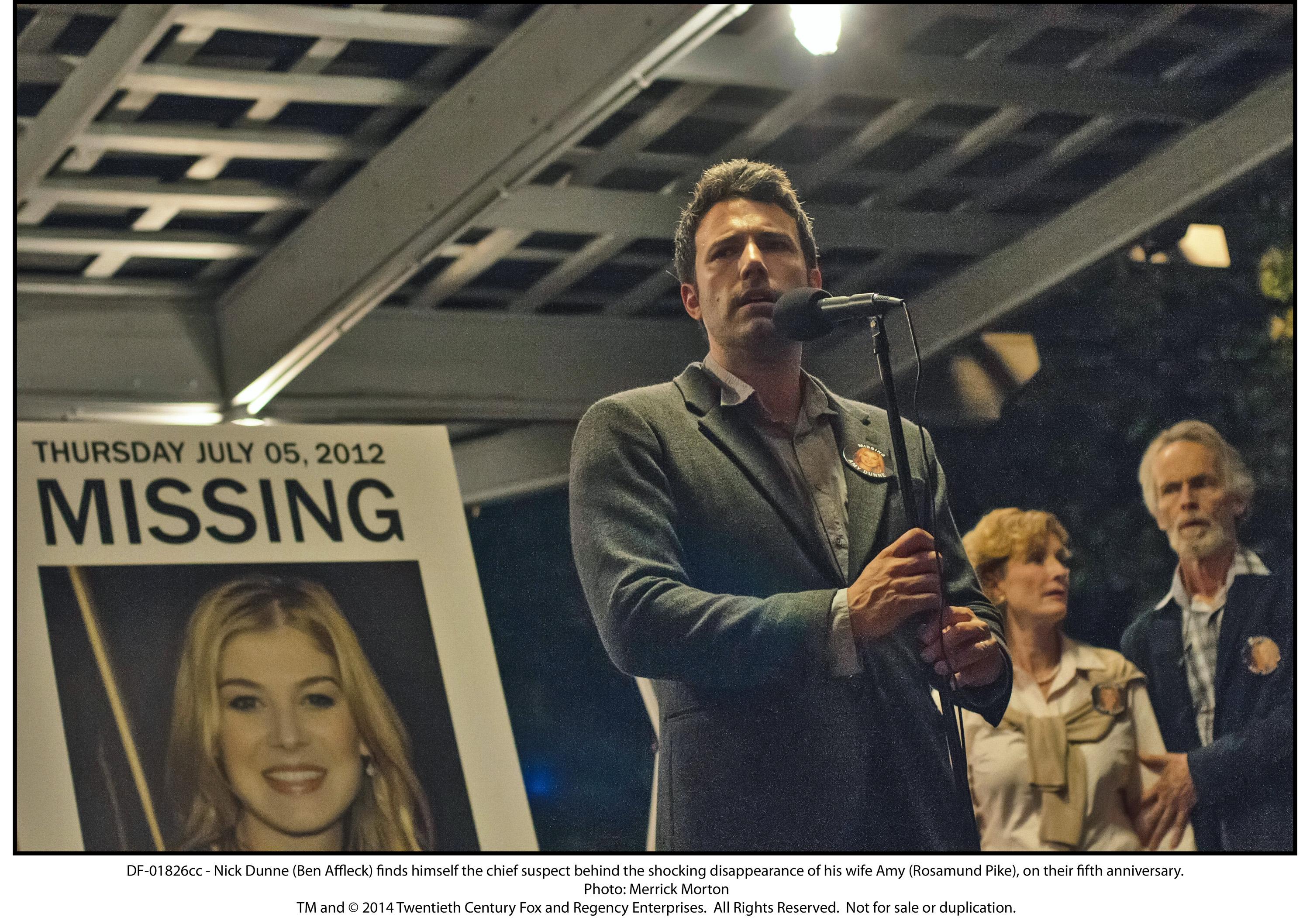

Apologies to Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part 1 is out Nov. 21; as always, all release dates are subject to change) and Reese Witherspoon (Wild, Dec. 5), but fall’s big-budget brigade is awfully male-dominated. That said, one of the season’s most-anticipated films — David Fincher’s take on the runaway best-seller Gone Girl (Oct. 3) — has quite the doozy of a female character (Rosamund Pike) to offset its double-sided lead (Ben Affleck). Fourteen more must-see (dude-filled) films below.

The Drop (Sept. 12) Tom Hardy and the late James Gandolfini star in this Dennis Lehane crime drama, which also has a puppy-themed subplot. Everybody wins!

A Walk Among the Tombstones (Sept. 19) and The Equalizer (Sept. 26) Thank you, Liam Neeson and Denzel Washington, for keeping the “lone-wolf badass” genre alive.

The Guest (Oct. 3) Downton Abbey escapee Dan Stevens stars in this creeper from indie horror auteurs Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett.

The Judge (Oct. 10) How’s this for casting: Robert Downey Jr. plays a hotshot lawyer; Robert Duvall is his estranged, retired-judge father who maybe killed someone.

Kill the Messenger (Oct. 10) Jeremy Renner plays Pulitzer-winning San Jose journalist Gary Webb in this thriller about the CIA’s suspected involvement in the crack epidemic.

Whiplash (Oct. 17) In this Sundance hit, a talented jazz drummer (Miles Teller) meets the music teacher from hell (the inimitable J.K. Simmons).

Fury (Oct. 17) Brad Pitt (and the haircut that launched a thousand hipster imitations) stars in David Ayer’s action drama, set during the last month of World War II.

Birdman (Oct. 17) Michael Keaton plays “a washed-up actor who once played an iconic superhero” (hmm…) in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s ensemble dramedy. Also aboard: Emma Stone, Naomi Watts, Edward Norton, and Zach Galifianakis.

Revenge of the Green Dragons (Oct. 24) Martin Scorsese presents this latest from Andrew Lau (with Andrew Loo), whose 2002 Infernal Affairs became the Oscar-winning The Departed (2006). Gangsters + revenge plot + 1980s NYC Chinatown = oh hell yes.

Interstellar (Nov. 7) Matthew McConaughey — already an expert on time being a flat circle, thanks to True Detective — has his first post-Oscar turn in Christopher Nolan’s drama about wormhole-traversing space explorers.

Foxcatcher (Nov. 21) Bennett Miller directs Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, and Mark Ruffalo in this true crime tale of two Olympic wrestlers and one murderous millionaire. Exodus: Gods and Kings and Inherent Vice (both Dec. 12) Better take work off this particular Friday, because Ridley Scott (with Christian “Moses” Bale and Joel “Ramses” Edgerton) is getting Biblical, and Paul Thomas Anderson (with an all-star ensemble cast, led by Josh Brolin) is adapting Pynchon. *