arts@sfbg.com

THEATER The sunny skies over Portland, Ore. were added incentive to bask in the summer coda offered by the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art’s Time-Based Art Festival, which ran Sept. 11-21. But the pretty green sheen that appeared one day on the surface of the Willamette River turned out to be a toxic species of blue-green algae. Scientists called it unprecedented for the river but an increasingly common problem in the Northwest due to the warming environment. And this unwelcome intrusion was like the best work seen in the final weekend of the festival, rousing one from a complacent slumber into something resembling a world out of balance.

One work in particular: Ground and Floor by chelfitsch, the brilliant Japanese company led by playwright-director Toshiki Okada. And, with limitations and reservations, the much-talked-about theater offering from France’s Halory Georger and Antoine Defoort, Germinal.

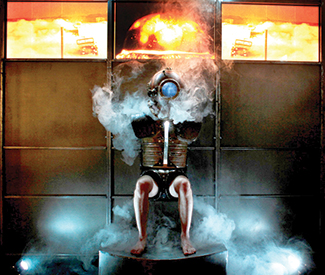

Germinal, which has been making the festival rounds, proved a deftly executed and designed work as well as a crowd-pleaser. The piece begins with supine bodies motionless on a darkened stage. Then the houselights begin to dim in a teasing back-and-forth pattern, and a dim orange pool of light collects on the stage with a similar coming and going, both calling attention to the mechanical artifice of the stage.

The four performers gradually sit up or stand, fiddling in silence with some portable consoles. Their manner is affectless, emotionally muted, like freshly shaped clay figures. Still, each has a distinct personality. One, Halory, discovers that by a certain manipulation of his console he can cast his thoughts (as supertitles) on the back wall of the stage. Soon the others are trying it. Soon one is doing it without the console. How about that? They think. They throw the consoles away. They can all do it!

They explore further. Who is whom, exactly, among these cartoon-like thought bubbles appearing on the back wall? It’s confusing, until Halory suggests they put their names before any thought. The question of being naturally follows for Arnaud, who ponders his name and its meaning. “It’s just that it raises a few questions about identity,” he explains. He, Halory, and the other male, Antoine, all sit and think on this as the woman, Odine, takes a pick-ax to the stage and unearths a live microphone. “I found something,” she tells her companions.

In this fashion, half-detached confusion and excitement intermingle with the humorous unfolding of dawn — the beginnings, it turns out, of a new world circumscribed by the physical and technological limits of the theater — as the characters not only explore and expand the possibilities for communication, but begin the process of classifying their world and its terms in what becomes an elaborate, evolving Venn diagram projected on the back wall.

This is a charming and intriguing beginning, and its elaboration over the course of the play offers more laughs and surprises, as the four continue to manipulate the elements of their world. But the conceit recapitulates philosophical and scientific categories without doing much more. This parallel universe might have been more interesting had it chosen to be truly different. But it starts to feel too familiar, without the critical distance that might have made the trip worthwhile. The play’s affirmative key rings out literally at points (as the four characters discover music as another “tool for communication”). But in the final crescendo, a chorus of affirmations grounded in an old-fashioned celebration of Reason, even the multiverse starts to feel a bit cramped.

If the optimism in Germinal came to feel like a retreat into comfortable certitudes, the brooding misgivings in Ground and Floor felt more in touch with the spirit of the times. Even playwright Okada’s setting of the play in some “future Japan” was riddled with a kind of ambivalence — the supertitle was followed by an afterthought that made it the “near future” instead. Ambivalence is the key of this piece of “musical theater with ghostly apparitions,” and it’s just for that reason that it remains rigorously, confidently, defiantly of this time and place.

The play concerns a family in which the living, the dead, and the unborn are all in an uneasy, imperfect relation to one another. A woman resists acknowledging the ghost of her mother in an attempt to shield her soon-to-be-born son from — what? “I am not going to see anything unpleasant,” she insists. Her husband gives a her weak encouragement as if from some distant place she barely registers. Her brother meanwhile announces he has at long last secured a job, and is restoring himself to a respectable position. But what is his job? No one asks, and he is wary of saying.

A wood stage raises the actors slightly, and a screen cut into the shape of a wide, squat cross acts as a screen for Japanese and English supertitles. The cast establishes a gentle, contemplative pace, delivering its performances with a kind of melancholy that resonates like a dream or the stunned aftermath of a disaster. The six scenes comprising the play are carefully juxtaposed to a shimmering, musing prerecorded score by Tokyo instrumental band Sangatsu.

The characters barely interact with one another, but are comfortable addressing the audience and commenting on the subtitles, pointing out the untranslatable gaps attendant on translation. These are maybe analogous to that gap between the living and the dead expressed here. The social fabric, covering time and space, is rife with holes. And the production succeeds by limning them quietly, pensively, even mysteriously, without any firm answers or blunt messages. Unlike the prototype-universe in Germinal, this weary place may be winding down but it does not feel yet like a closed system. *

http://pica.org/programs/tba-festival/