arts@sfbg.com

FILM They met at a comedy club in Brooklyn. Carlen Altman, a nervous comedian who moonlights as a Jewish rosary maker, was doing stand-up when filmmaker and Tisch graduate Alex Ross Perry approached her about collaborating on a project.

"I came down from the experience of having my first movie out there in the world," said Perry, who directed the little-seen indie Impolex (2009) when he was only 24. "I started thinking about success, disappointment and the way that people grow apart from one another."

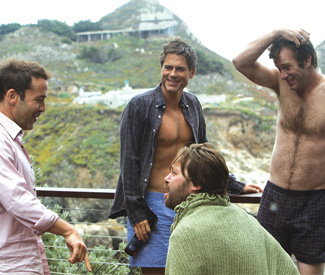

The idea for a brother-sister movie came to be. Altman and Perry, both 28, drafted the film in the summer of 2009 and shot it a year later. "You feel like you're stuck with someone and have been your whole life," Perry said of his time spent working with Altman on The Color Wheel, a droll and perverse take on vexed lives in transition, tinged with 16mm. Perry directed, produced, and edited the film while co-writing with Altman.

When the film begins, a dopey JR (Altman) shows up at the apartment of her misanthropic brother Colin (Perry). She is met with disdain by his girlfriend and by Colin, blue-balled by his stuffy long-term relationship. JR convinces him to help move her stuff out of her professor ex-boyfriend's place. Inevitably, their Northeastern road trip follows other tangents, taking the pair on a hilarious and sad journey that raises more questions than answers about their fraught relationship. They meet a lot of jerks, but no one more so than themselves.

"We were both really cranky filming," Altman recalled. "It [really] felt like we were brother and sister."

Both characters have had little personal and professional success, though JR, a would-be news anchor, even less than her brother.

Many of the characters' repellant mannerisms and frustrating habits are hewn from the real-life Perry and Altman — with exaggerations, of course.

"JR is more representative of what both of us actually feel and how we perceive ourselves in her creative ideas and lack of shame," Perry said. "My character represents the cautious side, what both of us feel like we should be doing."

Altman took the name of her character from a scrappy tomboy she once met at summer camp. "In terms of personality, my character is kind of my worst nightmare," Altman said of JR, who is really aggressive about success but has no specific passions of her own. "She's like 'Hey, look at me!' but, oh my god, there's nothing to look at. I feel shy about asking for favors, and I wanted to paint a picture of someone who is so not shy about asking."

Though the film is as talky, anxious, and self-revising as anything from the mumblecore school, Perry and Altman possess more maturity and even more cynicism than their profligate classmates. On the converse, their characters, filterless with no desire to grow up or shut up, are far behind everyone they encounter, from Colin's harpy high school crush to JR's haughty celebrity idol.

With all its zeitgeisty humor and lovably awful people, The Color Wheel takes some dark turns. What begins as a charming, dour comedy ends up viscerally queasy and pitiful, with its two leads as mixed-up as ever.

"The ending was my idea from the very beginning. It was easy to build it in a way that was natural and organic," Perry said of the film, which encourages, almost immediately, a repeat viewing.

Applauded by Cahiers du Cinéma and Mubi, among other cinephilic publications, The Color Wheel, a film that begins and ends in transit, no doubt has a long life ahead.

In the meantime, Altman wants to make a documentary about her Lionhead rabbit. And Perry, initially rejected by myriad producers and investors, hopes "there will be some traction after my two films," he said. "Maybe someone will help this guy."

Maybe someone will help these guys. *

THE COLOR WHEEL opens Fri/1 at the Roxie; also plays Sun/3 at the Smith Rafael Film Center.