arts@sfbg.com

FILM There is probably no clinical study proving that a penchant toward being devious, ruthless, or even sociopathic makes a person particularly inclined toward writing crime fiction. But it can’t hurt. Patricia Highsmith has been dead two decades now, and one suspects there are still a few breathing souls who’d enjoy dancing on her grave. A bridge-burning bisexual (at least one ex-lover committed suicide) who openly admitted preferring cats — and, oddly, snails — to people, she was prone even when sober toward rants of variably racist, anti-Semitic, and anti-whatever-else-you-got nature. The Texas-born, Manhattan-raised European émigré frequently seemed to hate her own gender and country. Famous and successful after the publication of Strangers on a Train in 1950 (and the release of Hitchcock’s film version the next year), she didn’t need to be nice. So, that worked out for her.

Abhorrent as she might have been in person, her misanthropy turned golden in print, most famously via the five — yes, just five — novels she wrote about the ingeniously amoral Tom Ripley over a nearly 40-year span. A man who gets away with everything, frequently including murder, fellow expat Ripley invents himself as whatever and whomever he pleases, burying evidence (and any inconvenient bodies) whenever he risks being found out. We root for him even as we recoil at his actions, because he’s simply taking advantage of the wealth and privilege others are too stupidly complacent to protect from people like him.

One shudders to think what Highsmith would have made of the 1999 film Anthony Minghella made of 1955’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (already adapted in 1960 by Rene Clement as Purple Noon). It’s a wonderful movie, but its compassion toward Matt Damon’s Ripley as a closeted gay man only pushed to violence by desperate insecurity is about as far from the author’s icy wit and admiration for the scoundrel as one can get.

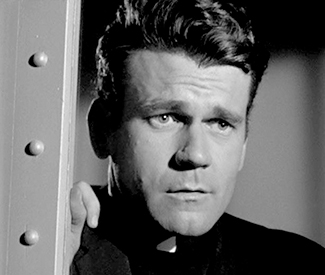

Ripley-free The Two Faces of January is presumably much closer to her intentions. The first feature directed by Hossein Amini, who previously wrote screenplays for a rather bewildering array of movies (from Thomas Hardy and Henry James adaptations to 2011 noir abstraction Drive and 2012 fairy tale mall flick Snow White and the Huntsman), it turns her 1964 novel into an elegant wide screen thriller very much of a type that might have been shot by Hitchcock, Clement, or someone else a half-century ago. You could even mistake Alberto Iglesias’ score for Bernard Herrmann at times. (Not the times when he’s lifting motifs whole from Arvo Pärt, though.) And if you still don’t think they make them like they used to, there’s Viggo Mortensen, Kirsten Dunst, and Oscar Isaac doing a damn good job of acting, and looking, like glamorous movie stars of yore.

Mortensen and Dunst’s Chester and Colette MacFarland meet the Isaac’s Rydal while they’re amid some sort of European grand tour in 1962 Athens — even staying at the Grand Hotel — and he’s a bilingual New Jerseyan of Greek descent eking out a living as a tour guide for Ivy League debutantes. Jaded, adventuresome types, the MacFarlands are intrigued enough to hire this openly gawking wannabe for a tour of the marketplace, then invite him and the Yankee heiress he’s momentarily snagged (Daisy Bevan as Lauren) for dinner.

It’s a pleasant evening they’d all soon file and forget. Or would have, if fate didn’t bring Rydal back alone to the couple’s hotel to return an item Colette carelessly left on the taxi seat. He finds Chester struggling with a man — whom he identifies as some drunk he’s simply wrestling back to his own room. But this fib thinly conceals a rapidly expanding sinkhole of criminality (already including major investment fraud and accidental murder) which Rydal now finds himself an accessory to. Rydal recognizes opportunity as well as risk in his new “friends'” urgent need to evade the authorities. But even as he helps them flee the hotel and city, he worries over the much younger, loyal yet nakedly vulnerable wife being dragged down by a “swindler” spouse. And as the awkwardly twined trio travels to less populous Crete, Chester (or whatever his name really is) worries his second wife — what happened to the first, anyway? — might well be swayed by someone as youthful, handsome, and blameless as Rydal.

At the one-hour point, The Two Faces of January looks, particularly in comparison to Mingella’s rather epic film (interestingly, that late director’s son Max is a producer here), like it might be something delicate yet rather simple — a portrait of a doomed marriage, its faults exposed by the third party the couple must take on amid crisis. But after this leisurely yet never boring buildup, Highsmith and Amini deliver so many harrowing complications you might end up shocked that this ultimately quite expansive seeming tale occupies just 96 trim minutes.

Mortensen, whose looks only grow more eerily, faultlessly chiseled with age, is so excellent-as-usual that one just has to shrug away puzzlement that he isn’t a bigger star — sufficiently occupied with his other creative outlets (painting, poetry, etc.), this actor clearly doesn’t care that he isn’t getting Brad Pitt’s roles, let alone his money. Having been raised in the system, Dunst would probably choose being Sandra or Reese if she could (and she certainly could, ability-wise), but fortunately the cards didn’t fall thataway. Now 34, she has the unfashionable heart-shaped facial prettiness of another generation’s wholesome starlets like Doris Day or Sandra Dee. If this particular role doesn’t begin to plumb the darker depths she’s more than capable of (as 2011 in Melancholia), it draws upon the same bottomless well of empathy she last tapped as another endangered spouse in 2010’s All Good Things. Which is, indeed, a very good thing.

As for Isaac, is this really the same guy from last year’s Inside Llewyn Davis? You can glimpse the same subtle, stage-honed technique in what’s superficially a much easier pretty-male-ingenue role. But yeesh: Looking like a fresh scoop from the same gelato tub that once surrendered young Andy Garcia, he sure cleans up nice. *

THE TWO FACES OF JANUARY opens Fri/10 in Bay Area theaters.