arts@sfbg.com

THEATER In one of the more arresting moments in Aaron Davidman’s new solo play, Wrestling Jerusalem, the Bay Area actor-playwright and former Jewish Theatre artistic director recounts being in a West Bank café with his Palestinian host when four young Israeli IDF soldiers enter in full battle gear. It’s an estranging moment for Davidman, a liberal American Jew on a hunt for answers to his quandary over Israel and its relation to occupied Palestine. But the estrangement he feels is complex, slippery: His first response is to feel estrangement from the soldiers; then a look of recognition from one of the soldiers opens up the difference between Davidman and his new Arab friends; but then Davidman also feels himself very much an American, not an Israeli — just where does he belong?

A self divided among multiple, conflicting affiliations and ideals is a general condition in this complex and stressful world, but it achieves a concentrated poignancy here for the artist son of progressive parents who rooted their liberal values in Judaic tradition. As a young man visiting Israel for the first time in 1992, Davidman had finally to face the contradictions that this would entail in the context of Israel as a Jewish homeland but also as a nation state and, especially, as a colonial power occupying Palestinian land. At the same time, criticism of Israel on the left alienates him when he sees it slipping into a broader pit of anti-Semitism — as he did during an antiracism rally at UC Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza in the immediate aftermath of 9/11.

Many return trips to Israel only made matters worse, more complicated, as his excursions became more purposeful — geared to interviewing people on both sides of the conflict — and his vantage extended into the occupied territories themselves. Grim details of that occupation come out in the course of this sure 85-minute solo performance, but so do voices justifying or qualifying the excesses of the Israeli state in the name of security and historical or political circumstance. While cleaving to core values of equity and justice throughout, Davidman respectfully represents views that range to extreme points on either side of the messy debate.

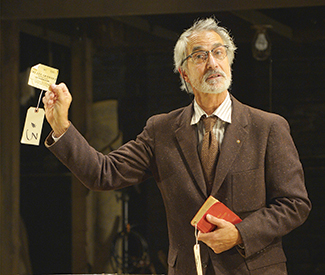

At the same time, the act of doing so becomes its own trauma. As if in a state of possession, Davidman manifests the inner and outer turmoil in a physical performance marked by often-anguished gestural passages, stirring liturgical verses, unexpected humor, and a series of neatly etched characters. These come all the more forcefully across for being set in an intimate thrust stage arrangement, carved into the central space at Intersection for the Arts. There the play unfolds against scenic designer Nephelie Andonyadis’s beautiful cloth backdrop, dyed in muted desert tones that come atmospherically alive in Allen Willner’s blood-and-earth–hued lighting design.

On one hand, Wrestling Jerusalem‘s airing of opposing views is as timely as ever. News of human rights abuses and more violence in and around the occupied territories comes almost daily, while the US State Department once again meanders down its long and winding road to nowhere with respect to jump-starting “peace talks.” Meanwhile the growing BDS (Boycott Divestment Sanctions) movement across US campuses and around the world is meeting with increasing right-wing pushback (most recently at Northeastern University). And new books by prominent American Jews and gentiles — most recently the New Republic’s John B. Judis — dissent from the usual narratives around Israel-Palestine, stirring charges of apostasy (and anti-Semitism).

On the other hand, for these very reasons Davidman’s measured search for understanding and balance can seem slightly behind these urgent, increasingly polarized times. Directed by Michael John Garcés of Los Angeles’s Cornerstone Theater, the play rehearses mostly familiar, albeit still charged and important, arguments. Its most persuasive aspects instead lie in Davidman’s representation of his personal journey, the expansion of conscience and understanding it spurs. While its mingled voices intentionally unsettle the mind and emotions, they achieve a tentative truce in the play’s final affirmation.

That affirmation — a recommitment to core values that are both traditional and universal — in turn opens common ground in which all might enter. Far from over at this point, the conversation is just getting under way. Pairing performances with something he calls the Peace Café, an opportunity for direct dialogue among audiences members, as well as other post-show discussions moderated by professional mediator Rachel Eryn Kalish, Wrestling Jerusalem is less a political argument (though it contains several) than an invitation to dialogue. Maybe more importantly still, it’s an invitation to listen. *

WRESTLING JERUSALEM

Through April 6

Thu-Sat, 7:30pm; Sun, 2pm, $20-$30

Intersection for the Arts

925 Mission, SF