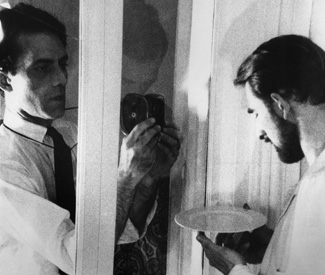

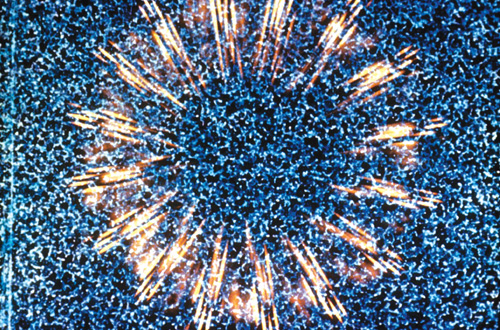

FILM/LIT It’s anyone’s guess how many films and videos George Kuchar made before his death in 2011 (Portland’s Yale Union is valiantly attempting a comprehensive retrospective, which they estimate will take seven years), but there’s material for at least a hundred more in The George Kuchar Reader (Primary Information, 336 pp., $27.50). Tracing a singular life in movies from the Bronx-bound 8mm melodramas Kuchar made with his twin brother, Mike, on through the boundlessly nutty video conflagrations emerging out of his classroom at the San Francisco Art Institute, the book collects handwritten screenplays, letters, underground comics, meteorological observations, and UFO diaries. Reader editor Andrew Lampert will be in attendance at two special screenings in the coming weeks to report on these deep-sea dives into Kuchar’s self-described cinematic cesspool.

That Kuchar’s literary artifacts should be hilarious and not a little wise is no surprise, but it’s worth pausing to note the extent to which the writing itself illuminates Kuchar’s creative methods. Take the letters of recommendations he wrote for his SFAI students — an obligatory form of writing if there ever was one, but for Kuchar an occasion for uninhibited characterization: “This winged spirit, reared in semitropical heat, can banish the chill that has descended upon your patrons; so turn up the heat and witness what only equatorial nearness can nurture”; “His unbridled lust for livid living endows the fruits of his labor with intoxicating incense. Sniff these works at your own risk as the aroma reeks of secret scents from a Garden of Eden gone mad with flower power”; “He’s a lone figure swimming upstream to a different drumbeat.” No cliché is safe. Kuchar’s persistence in slugging it out with these once familiar figures of speech surely says something about the way he approached a dramatic scene.

Implicitly skewering heroic strains of avant-garde poetics, Kuchar’s accounts of his own filmmaking almost always turn on the body. Take this metabolic account from a 1964 article for Film Culture:

“Many nights I lay awake in my sheets burning with the fever of a new movie script … Sleep only comes when extra sugar is pumped into my body due to the excessive emotional tension that grips me during these celestial periods. The sugar makes my body hot thereby opening its big pores. Then the sweat of my ordeal seeps out in a stink of creativity and new germ has been born. A germ that will grow into the virus of 8mm movies. In the morning I awaken, fresh, vibrant, but constipated with the urge to release a lump of cinematic material.”

So filmmaking is fever, open pores, sweat, stink, germs, and viruses; the film itself, a load of shit. One begins to sense that the many Joycean digressions on “exciting gastric distress” peppering these pages are less a matter of any particular tummy trouble than Kuchar’s underlying conviction that the creative muse is ineluctably bound to more basic drives.

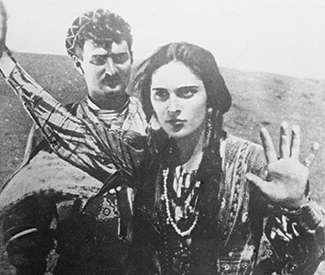

Bodily fixations notwithstanding, Kuchar was plenty canny about film aesthetics, whether pinpointing the underlying motivations for “these gigantic, moving billboards” (“IT WAS LOVE AND OBSESSION”) or situating his own fortuitous ascendancy in the 1960s avant-garde: “You’d develop them [8mm films] cheap at the local camera store and in five or 10 years the emulsion would crack and chip in time for the 1960s, avant-garde film explosion. No need to bake your footage in an oven like so many artists were doing: your home movies had already deteriorated into art.” Not that Kuchar wasn’t grateful: An early letter to Donna Kerness evinces little enthusiasm for his work as a commercial artist but adapts a more familiar exuberance when describing his latest 8mm production about a brawling ménage-a-trois.

The final 50 pages of the Reader are dedicated to a poignant last testament stitched together from the “endless emails of unexpurgated excess” Kuchar sent Kerness in 2010-2011. Even in his teenage letters to Kerness, it’s clear that Kuchar felt unusually at ease writing to the star of his Corruption of the Damned (1965). Describing an earlier melodrama, he writes with unusual candor how “I was very inspired by Arlene and her kin. They are very mixed up and sometimes they are damaging their lives but I like them anyway probably because I’m just like them.” Fifty years later, sick with love and cancer, Kuchar treats Kerness more as a confessor than a confidante. “Anxious to reveal secrets I usually kept under wraps,” Kuchar doesn’t spare any detail in describing his yearning for a long-time “midnight caller” named Larry: “Instead of realizing that he’s just what you call a sex buddy, I turn the whole thing into a live or die, Victorian romance.”

Even in his hour of darkness, Kuchar couldn’t help but seeing his own trials as material for a grand melodrama. “Being the egotistical movie director that I am, I want the motion picture of my life to be an X rated, inspirational saga of the nerdy Bronx kid who walked the red carpets of Hollywood while flirting with the red light districts of Sin City.” In a more reflective mood he writes to Kerness, “Expressing all this in certain chosen words and constructed sentences made the mental and medical troubles take a back seat to creative engineering: an arrangement of letters and punctuations to coalesce the chaos that contaminated my cranium.”

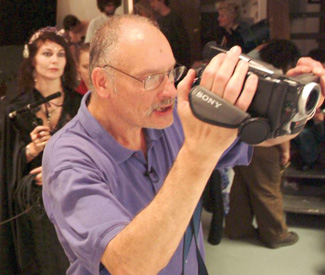

Kuchar writes of depressive anxiety, rampant insecurity, sexual hang-ups, and plenty of confusion in the face of “getting old and dreaming young” — but not a word of boredom. “Since I’m an actor anyway, I see the personal issues I penned (or typed) as emotional motivations in an ongoing (for a time anyway) B-movie.” B-movies aren’t really a wellspring of inspiration; that was all George. A final photograph shows him standing in front of a Denny’s, eyes on the skies like always. 2

OFF THE SCREEN: MOVING PICTURES AND WRITTEN WORDS: CELEBRATING THE GEORGE KUCHAR READER

Oct. 15, 7pm, free

Exploratorium

Pier 15, SF

A CRIMINAL ACCOUNT OF PLEASURE: THE GEORGE KUCHAR READER

Oct. 18, 7:30pm, $8-10

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

701 Mission, SF