arts@sfbg.com

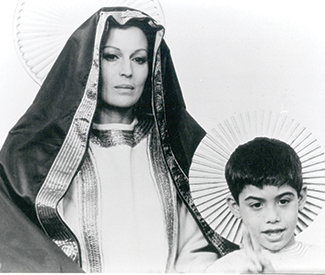

FILM Anthony Mann was one of those directors only really appreciated in retrospect — during his life he was considered a solid journeyman rather than an artist. It didn’t help that when he finally graduated to big-budget “prestige” films at the dawn of the 1960s, he was unlucky. He left 1960’s Spartacus after clashing with producer-star Kirk Douglas. (Stanley Kubrick famously replaced him.) He left the 1960 Western epic Cimarron mid-shoot after an argument with its producer, though its poor result was still credited to him, as was A Dandy in Aspic, a 1968 spy drama completed by star Laurence Harvey after Mann died of a heart attack very early on.

He had done very well indeed with 1961’s El Cid, a smash considered one of the few truly good movies resulting from Hollywood’s then-obsession with lavish historical spectaculars. The same judgment is now granted 1964’s The Fall of the Roman Empire, to a more qualified degree. But that film was so titanically expensive it would have stood as the decade’s monument to money-losing excess had 1963’s Cleopatra not already claimed that crown.

Today Mann is probably best regarded for the series of Westerns he made in the 1950s, many starring a more tormented, less aw-shucksy James Stewart. They’ve tended to overshadow the film noirs that in turn preceded them. The Pacific Film Archive is doing its bit to correct that imbalance with “Against the Law: The Crime Films of Anthony Mann,” a three-week retrospective spanning a brief but busy period from 1946 to 1950.

Surprisingly for a talent associated more with action than talk, the San Diego-born Mann first made a modest name for himself as a New York stage director and actor. In 1938 he was invited by Gone With the Wind (1939) producer David O. Selznick to come to Hollywood as a casting scout, then moved up to assistant directing at Paramount (including for Preston Sturges). He was soon deemed fit to direct low-budget features, starting in 1942 — cranking out cheap musicals like Moonlight in Havana (1942) and melodramas like Strangers in the Night (1944) for the bottom half of double bills. His craftsmanship was already strong even if the scripts were weak. To compensate, he began early to concentrate on evocative visual storytelling whose impact could cover the flaws of corny dialogue and situations.

Strangers and first PFA title Strange Impersonation (1946) were proto-noirs that allowed him to up his game. But what really altered his career course was the founding of a new company, Eagle-Lion, that he started working for the following year. There, budgets remained “Poverty Row” low, but more creative freedom was allowed — and he gained a key collaborator in now-revered cinematographer John Alton, who famously said “It’s not what you light, it’s what you don’t light.”

Alton’s often highly stylized, chiaroscuro images lent rich atmosphere and suspense to what were then considered “semi-documentary” shoot-’em-ups. Their first collaboration, 1947’s T-Men, was a highly influential sleeper hit that took its realism seriously enough to start with an audience address from an actual former Treasury Department law enforcement official. The “composite case” ensuing has Dennis O’Keefe and Alfred Ryder as undercover feds who infiltrate a counterfeiting ring in Detroit — one losing his life in the process.

O’Keefe returned on the other side of the law for the following year’s Raw Deal, playing an escaped con determined to avenge himself on the crime boss (future Ironside Raymond Burr) who betrayed him. He travels with two women, one adoring (Claire Trevor), one unwilling (Marsha Hunt) … at least at first she is. This is the rare noir narrated by a moll, as Trevor’s faithful doormat comes to terms with losing the man she’s always loved to the “nice girl” he’s taken hostage. There’s a bitter romantic fatalism to her perspective that’s as masochistic as it is hard-boiled.

The PFA offers two features from 1949. Even more “documentary” in its procedural focus than T-Men, He Walked by Night (officially credited to Alfred Werker, though Mann directed most of it) “stars” the LAPD as its personnel hunt a sociopath clever enough to disguise his tracks as he goes on a murder spree. Focusing on the minutiae of investigative procedure (“Police work is not all glamour and excitement and glory!” our narrator gushes), yet full of visual atmosphere, it was widely considered the uncredited inspiration for the subsequent radio and TV serial Dragnet. (Jack Webb even plays a forensics expert.) The then-inventive location work culminates in a deadly chase through LA storm drain tunnels. Border Incident, unavailable for preview, anticipated the Native American rights-centered Devil’s Doorway (1950) in its forward-thinking treatment of racial minorities — here Mexicans caught between smugglers, bandits, and US immigration agents. It was originally entitled Wetbacks, a moniker that would have ensured lasting notoriety, albeit at the cost of obscuring the film’s anti-discriminatory theme.

Director and DP soon parted ways, alas. Their third 1949 collaboration (the next year’s Doorway would be their last) is not in the PFA retrospective, although it ought to be: Reign of Terror, aka The Black Book, is set during the French Revolution, yet it’s as thoroughly, baroquely noir as any movie involving powdered wigs could possibly manage. *

AGAINST THE LAW: THE CRIME FILMS OF ANTHONY MANN

Feb. 7-28, $5.50-$9.50

Pacific Film Archive

2575 Bancroft, Berk.

bampfa.berkeley.edu