arts@sfbg.com

THEATER How we hear — or if we hear — is to some extent a matter of association. We’re inclined to listen to, take seriously, and treat as equal those people with whom we identify and can sympathize, people who seem to share basic things, including certain values, with us. Such is the implication (and provocation) in English playwright Nina Raine’s engaging drama, Tribes, which roots itself in an eccentric London family — one of whose members is deaf — in order to explore wider social questions of affiliation and communication, exclusion and indifference. The play in this way takes on literal and metaphorical deafness, exploring clan-like thinking and behavior in and through the politics of the deaf community.

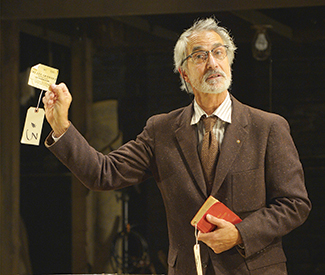

The serious questions at the heart of the play, however, come agreeably packaged in a very loud and amusing family of cantankerous extraverts headed by a former scholar turned author named Christopher (a gruffly and charmingly expansive Paul Whitworth) and his wife, a novice novelist named Beth (a cheerful yet concerned Anita Carey, in an admirably supple performance). The household has recently expanded to former proportions with the return of grown 20-something children Sylvia (Nell Geisslinger) and Daniel (Dan Clegg), who rejoin their grown and deaf brother, Billy (a sympathetic, impressively complex James Caverly), around the family’s book-lined living room (in Todd Rosenthal’s detailed, naturalistic scenic design, which transforms when necessary into offsite locations or inner spaces via Christopher Akerlind’s mutable lighting and Jake Rodriguez’s evocative sound design).

We meet this dysfunctional, codependent set of oddball overachievers and outcasts around the long table to the left of center stage, where they engage in clearly quotidian bouts of whining and dining. “Why am I surrounded by my children again,” wonders Christopher rhetorically. “When are you going to fuck off?”

Playwright Raine has an ear for the kinds of cruel jabs, off-color remarks, and outrageous propositions that, it seems, only a family can indulge in (let along get away with) without so much as a tremor of trepidation or regret. In this smarty secular Jewish household, that sniping is especially vituperative, colorfully earthy (especially in Dad’s frequent bon mots), and colored over by an intellectual hue: Christopher’s pet theme is the rootedness of feeling and personality in language. Daniel, plagued by a damning superego that has produced condemnatory voices in his head, is writing a thesis more or less arguing the opposite — that language does not determine meaning. His socially awkward sister, meanwhile, has taken up the pursuit of music (where feeling transcends language), singing opera in pubs. Moreover, despite their constant assailing of one another, there’s a collective pride undergirding it all — a satisfied sense of the family’s own positive difference from the rest of the (alternatingly intimidating and pitiable) world.

But, notably, these animated discussions among the family tribe, with which the play begins, rarely include Billy. When he speaks — in the pronounced but muted tones of someone who does not completely hear his own voice — it’s usually to ask what everyone else is talking about. Treated as an equal (with a nonchalance bordering at times on indifference) and yet simultaneously eclipsed by his loudmouthed, self-involved relatives, Billy ironically stands out (to us) by virtue of his quiet remove.

He soon breaks free and into clearer view after meeting a woman named Ruth (a sharp and vital Elizabeth Morton) with whom he falls instantly in love. Ruth is losing her hearing, but coming from deaf parents, she is well acquainted with the community and culture of the deaf. This does not make her transition any easier, however. Indeed, it complicates it in subtle ways. More than any other character, she straddles both worlds: the hearing and the non-hearing. It makes her both threatening and attractive to Billy’s family, who fear Billy’s categorization and cooptation as part of a deaf minority.

Billy, unusually adept at lip reading and emboldened by his love for Ruth and the community she provides access to, takes a job with a law court providing crucial transcriptions from audio-less video for criminal trials. This allows him to move out of the family home for the first time. Ruth teaches him ASL, which he begins to use more and more exclusively. Both he and Ruth meanwhile confront a family that places a premium on the connection between language and feeling. From this constellation of voices and positions, a serious split emerges that throws the family into a tailspin while asking a series of stimulating questions about where, and how, we belong.

Raine’s 2010 play (originally produced by London’s Royal Court Theatre) gets a spirited, involving production from Berkeley Rep and director Jonathan Moscone. Moscone (the artistic director of California Shakespeare Theater who excelled at another contemporary family-social drama when he helmed Bruce Norris’s Clybourne Park at ACT) stirs the hornet’s nest of mad, madcap family living with an expert hand, and his fine cast delivers Raine’s witty (albeit sometimes too thematically forceful) dialogue with precision and ease. If the play wraps up a little abruptly, it also leaves much in the ensuing silence to continue listening to. 2

TRIBES

Through May 18

Tue and Thu-Sat, 8pm (also Sat, 2pm); Wed and Sun, 7pm (also Sun, 2pm; no 2pm show May 18), $29-99

Berkeley Repertory Theatre

2015 Addison, Berk