THEATER About two years ago, a small band of Brits came on an exploratory mission from the South of England to the Bay Area. They wanted to discover what, if anything, they had in common with their American counterparts in the theater world. The trip ended with a party in the Mission, where UK performance duo Action Hero performed A Western for their new friends way out West.

And that might have been that. But a year later, in 2012, Action Hero (Gemma Paintin and James Stenhouse) was back, this time leading a workshop-residency at CounterPULSE. This collaboration with local artists (six people drawn mostly from the experimental dance and performance world) produced a one-night smorgasbord of performance, complete with a dining area, a menu, and a wait staff to bring you to your performance when it was ready.

The evening was also a lively mixer, in which a friendly, jocular man named Ben Francombe — head of the pedagogically radical theater department at the small arts-focused University of Chichester in West Sussex — was an enthusiastic participant.

As Francombe explained at the time, the school of performing arts at his university was eager to maintain contact with places like CounterPULSE as a partner in creative exchanges. “We share a commitment to the idea of ‘exchange’ in creative processes,” he wrote, in an email correspondence shortly before arriving in San Francisco, “and how artists develop methods of working through sharing ideas that are ‘foreign’ and different from their established practice. As an arts-based university, we are very interested in exploring ways in which our international connections stimulate our cultural ideas.”

He added, “As a department we have a unique commitment to developing small-scale artists, and exploring radical ideas on the nature of theater and performance through facilitating interesting artists in interesting creative contexts.”

That sounds good on paper, but what would it really mean in practice? The Chichester folks were the first to admit they didn’t really know but were seriously interested in finding out, as long as their counterparts here were game to work on it together.

It turned out many were. The call for a joint programs of exchange geared to artist-centered new work found receptive ears among the experimental dance and performance makers gathered around CounterPULSE — whose working methods are already more or less akin to the devised approach facilitated at Chichester — but it also attracted people in the theater scene, where devised work (ensemble-driven theater built from the ground up) has its champions in companies like Mugwumpin and the work of artists like playwright-director Mark Jackson and actor Beth Wilmurt, co-creators of The Companion Piece at Z Space in 2011. Indeed, Z Space was soon onboard for more contact across the pond. Meanwhile, Jackson, Wilmurt, and CounterPULSE’s Julie Phelps all went over to Chichester in February of this year to see the university’s theater-performance MA program in action.

This year, Chichester’s open-ended and open-minded dialogue with San Francisco’s theater and performance scene ramped up considerably with a just completed summer intensive at Z Space. And there’s more just ahead, including a festival of devised performance in October (at CounterPULSE) and, if all goes well, the inauguration sometime in 2014 of an international MFA program in theater-performance making exclusively linked to San Francisco.

“We decided to come here a couple of years ago,” says Louie Jenkins, a solo artist and Chichester faculty member who led the summer intensive in partnership with Mark Jackson. (Jackson has detailed the evolution of his involvement with, and his firsthand experience at, Chichester in an editorial promoting the intensive in Theatre Bay Area magazine.) “[We were] trying to understand what was happening here and whether what we did fit in with the ethos here. So we met with these different people. And the sense we had was that this was a fertile place.”

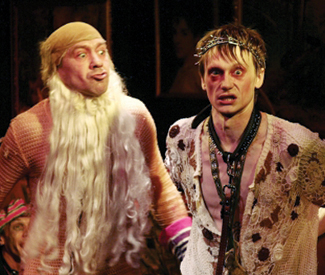

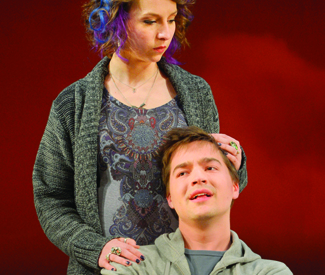

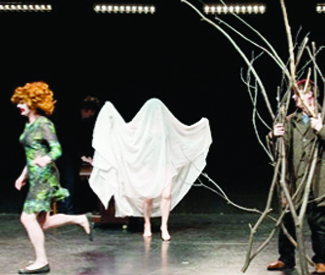

The summer intensive involved 16 artists, including several Chichester masters students mixed in with the disparate group of local theater, dance, and performance practitioners. It also came with a public component, designed to further introduce this type of work to local audiences. This included a showing of MA student work and a shrewd little piece by Box Tracy Theatre Dance Company (Nixx Strapp-Freeman and Valerie Watkinson) at CounterPULSE.

It also included last Saturday’s completely sold-out showing at ZBelow of work generated during the intensive — four pieces by four groupings of British and local artists. No director, no playwright, no set designers — the artists did everything, being responsible for the whole experience. The title of the evening was “Unfinished Business,” and yet it felt startlingly complete as an evening of performance. Still, the title is both apt and promising. At the same time, it was arguably one of the more exciting things to happen in a local theater for a long time.

“We often talk about accidents,” says Jenkins, whose own history as an artist and resident of San Francisco in the 1990s inspired Chichester’s initial foray into the Bay Area. “Out of this process of trying to make work, an accident will happen, and that becomes what the piece is about. I know it’s a luxury to have time and space to be able to look at the processes, but in [the usual mode of theatrical production] there is very little flexibility for mistakes to happen, for accidents to happen. I think that is when the excitement comes into theater.”

For information on the MFA program as it emerges and for details on the formal launch in October 2013: www.chi.ac.uk/theatremaking