Los Angeles’s Teatro Jornalero Sin Fronteras makes common cause with Santa Rosa’s the Imaginists

(Note: what follows is an extended version of a story and interview that appears in this week’s Guardian.)

A white passenger van pulls to the curb in a largely residential Spanish-speaking neighborhood in Santa Rosa, discharging a group of Latino men and women at the door of a converted warehouse. The visitors vary by age, class, and education. All hail from Mexico or Central America, but more recently Los Angeles, where they’re among the cities thousands of jornaleros, or day laborers, making their way job by job, often without secure documentation, or much security of any kind.

Standing beside the warehouse on this quiet street, they could be mistaken for an ad hoc work crew. But the warehouse is a theater, and this sunny afternoon in June is the culmination of a precious week off. Not that these men and women aren’t here in Santa Rosa to work — just this time it’s on a play.

Brent Lindsay and Amy Pinto, founders and artistic directors of the Imaginists, greet the visitors warmly as they collect outside the theater and slowly saunter in, joining other members and friends of the Santa Rosa company inside its spacious single room, together with their small children. The two groups have known each other barely a week, but already seem more than colleagues — more like extended family.

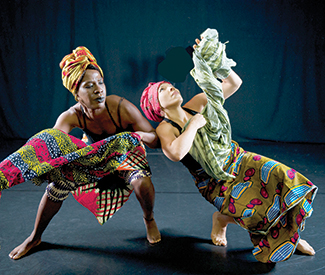

It’s the final day of a weeklong artistic exchange between the Imaginists and Teatro Jornalero Sin Fronteras (Day Laborer Theater without Borders), a Los Angeles–based Spanish-language ensemble theater created by and for the immigrant day laborer population. The ten-member troupe, founded in 2008 under the umbrella of LA’s Cornerstone Theater and led by co-artistic directors Juan José Mangandi and Lorena Moran, has so far created 15 short plays that they perform mostly at day laborer centers across Los Angeles — although this last year saw TJSF tour both Northern California and El Salvador. The plays examine everything from the legal and human rights of immigrant workers to health issues to the transnational cultures migrant workers share and foster.

After some socializing over a light breakfast of coffee and pan dulce, the two companies gather in a circle for some warm up exercises led by both Lindsay and Moran. One particular challenging memory game provokes mild frustration and laughter. “This is why we do this exercise,” explains Moran to her actors, all amateurs and volunteers united by the unique opportunities their theater has offered them. “We need to connect to another person and remember details about them.”

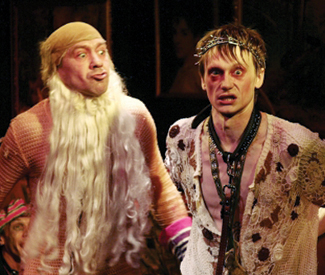

Then they all get back to work on a playlet they’ve been developing from improvisations. It begins with two workers who alternately pay off and slip by a snoozing guard (played by Imaginists company member Eliot Fintushel) to dump toxic waste into a nearby stream. When this causes an environmental disaster, a government spokesperson (played by Pinto) assures people in the audience that their organic produce is safe. Meanwhile, a cleanup crew of migrant workers is slowly poisoned to death. A news team rushes to the scene of the eco-disaster, but seems to take no notice of the brown bodies sprawled over it. Left alone onstage, the workers rise as ghosts — beginning with one who sings, “They’re carrying me off to the cemetery. Don’t anyone cry for me. Just sing my favorite song…” — and one by one exit the stage.

Throughout, Lindsay directs from a chair audience-side, giving advice or suggestions at various points. All, however, are welcome to chime in with comments and do. An elderly woman named Adela Palacios, for instance, suggests that before departing the stage each ghost can simply state their name and what they did for a living, a suggestion readily embraced by all. Soon the form of the scene has a solid arc, and the action gains many subtleties, as well as a tone that makes a virtue of the mix of amateur and professional actors. Combining slapstick, winking asides, an eerie sense of tragedy, and a moving use of direct address, it’s a surprisingly affecting bit of work.

“We come to the theater as older people,” explains Moran. “But we feel we’ve found a company [in the Imaginists] like us. We share the same path.” A native of Guatemala who worked in business administration before fleeing domestic abuse and the country, Moran (translated by Gustavo Servin, a young member of the Imaginists) speaks eloquently about the company she joined five years ago amid a dangerous working life that was both foreign and alienating to her. She acknowledges frankly, “Theater saved my life.”

TJSF is currently developing its first full-length play, Caminos al Paraíso (Paths to Paradise), written by Mangandi and directed by Moran. This exchange in Santa Rosa, made possible by a grant from the Network of Ensemble Theaters, has offered TJSF the opportunity to learn important technical aspects of crafting a full evening’s production from their more experienced colleagues. At the same time, it’s offered the Imaginists, which has grown into a bilingual company since rooting itself in Santa Rosa, a chance to advance their own mission through contact with a deeply community-driven Latino theater. But neither motive really captures the personal ties and mutual respect that have been forming here, the subtle and profound reciprocity of influence, and the solidarity emerging from it all.

“TJSF is a brave, important theater company that is telling stories that we don’t usually hear,” reflected Amy Pinto recently by email. “They tell them with humor, with heartache, in a group, in Spanish. Coming together for a week, we were able to strengthen our own resolve to tell these stories, not to be afraid of being deemed ‘political.’ For the Latino members of the Imaginists, the exchange was a catalyst to take ownership and be empowered by their histories and stories. This exchange reinforced how necessary it is to have comrades, to share experiences and methods, to have a network of support throughout the country for this work.”

The Imaginists plan to travel to Los Angeles for another face-to-face meeting with TJSF over next steps. Together they hope to develop something that can tour to labor centers across the country.

In the meantime, inspired by the exchange, the Imaginists are concocting a new play, based on a famous children’s story, which will address the plight of undocumented people. Working title: REAL.

“For Teatro Jornalero there is no division,” notes Pinto. “They are telling the stories of their lives. They are humanizing a ‘political’ situation. We have to let that sit in us, that uncomfortability — can we turn our politics off and on? No. Everything in art is a choice.”

She adds that the encounter held surprises for them too. “To have an encounter where all your expectations are turned upside down,” she marvels, “theater can do that. We are changed. There was so much laughter the entire week. And a fare share of tears.”

Voices from Teatro Jornalero Sin Fronteras

The following excerpts are from conversations that took place on Saturday, June 22, at the warehouse theater of the Imaginists in Santa Rosa. Members of the Imaginists and Teatro Jornalero Sin Fronteras had just completed their rehearsal, ahead of a public performance that evening, and were seated in a semi-circle to answer a few questions about their collaboration. Translation was provided by Julie Kaiser.

SF Bay Guardian Can I ask a general question of the members of Teatro Jornalero? Anyone who would like to answer please do. What brought you to the company, and why did you join? What does being in the company offer you?

Teatro Jornalero Sin Fronteras My name is Alberto Scareño. I found out about this when some of my friends told me about it. It was really interesting, so I called them up to see if there was a spot for me. They said, sure, come that day. And I went in. I’ve never been an actor. We started with exercises. It was really interesting and relaxing. Sometimes I have a lot of stress, or I’m just mad, and to come to this place that relaxes me — it relieves my stress, and time flies. Now what I hope for is to work with even more verve and learn more about the theater.

SFBG What kind of work do you do to make a living?

TJSF Every morning I go out and look for work at a corner in central Los Angeles. I’m a day laborer.

SFBG And you still find energy after a long day’s work for theater?

TJSF The deal is, I don’t get work everyday. So if I don’t work one day, then I have energy to go. When I work, I’m tired, but I get there, and I get my friends, and we do the exercises and I relax. And it’s fascinating.

SFBG Anyone else?

TJSF My name is Xico [pronounced “Chico”] Salvador Paredes. I was on a workers’ corner in California — I’d joined a battle to have a [day laborer] center made — and the first person that [I met] was Juan José. He had participated in theater as an actor, and he was starting to work on his play about illegals. Then he invited me and Lorena [Paredes is married to artistic director Lorena Moran], and other guys, to work in theater. At first I didn’t like it, because I’m a worker: I just get work, get work, get work — I’m not interested in anything else. I send money [home]. That was my only vision, to have a day of work.

But after I came in, I realized, it’s a weapon for communication and understanding, a means of connecting with other people. We started to create pieces out of our own experience, and to recreate our experience. It serves to take out of us what’s inside of us, and to let us know that we’re not alone. The best part of being in this theater is that we’re getting together with people who don’t know what a day laborer is. A day laborer stands on a corner. In the morning he’s cold. He doesn’t have anything to eat. He doesn’t have the security he’s going to actually get work. People walk by and say, “Oh what a lazy guy,” or they pass by as if you’re just a tree, because you’re just standing there all the time. Nobody understands what you’re doing standing there. But a day laborer has huge hope. And he doesn’t know if he’s going to get work. And that’s us.

With the theater, we’ve told many people about what a day laborer is, and shared with those who don’t know anything about their rights. Now we can say, “This is what it is.” It’s really difficult. I just got into a situation where I’ve gotten into the deportation process. I’m in the struggle, but I also have to go to court. I have to do lots of things. And I might get deported. I came here not just to work; I came here to tell my story. And my story’s big. No bigger than anybody else’s. But it’s very positive for people to hear: Here we are.

TJSF I’m Mario Rivera, and I’m very happy to be here sharing with you all. I’m also, like my friends here, a day laborer and I work in central Los Angeles. I came into the theater because I was invited by Lorena. What I like is learning from my compañeros. I had nerves when people looked at me, and I lost that. I lost that fear, and I really like being here. I’d like to learn more from everybody. And I like the play that we’re doing here [with the Imaginists]. This all suits me. I like all of this.

TJSF I’m Adela Palacios. And I’m not very good for talking. The reason why I’m in the theater is because I don’t have work. I studied nursing. Two times I graduated in nursing. I am a nurse. But I had an accident. Now I can’t find work. In this country there’s a lot of discrimination about age. I looked for work for two years. The only opportunity I’ve found, that opened doors for me without discrimination, was this theater. We are volunteers. We don’t have work. They help us. Sometimes they give us food. I am very grateful to this great person, Lorena. And I’m very grateful to Cornerstone Theater. We have some understanding there. We are not heard as we should be [in society], but they do a little, what they can. They give us a little bit of a normal life. My stress is better than it was. And they’ve done everything possible. They do what they can. They can’t do more. I’m really grateful. You have to accept what there is and not ask for much.

TJSF I’m Heidi Guevara. My problem is I have a fear of being in front of people. But now it’s gone. I didn’t think I’d ever do something like this, because I’m really embarrassed easily. Now I have the courage to be in front of people. Lorena gives us exercises. And they help you to use your voice and express yourself, to overcome your shame. It’s a little complicated, but I’m learning more little by little. And here we go! I’ve been with them one year — you have to keep learning and learning. You know this. You have to keep going and learning. Little by little, but I’m going. Thank you, Lorena.

TJSF My name is Raul Salinas. I’m from northern Mexico. Chihuahua. I have six kids. I’ve been ten years here. Now I’m in the Centro Jornalero for work. I don’t have full-time work. I’ve been with the theater three months. How did I get here? I don’t know. It was just chance. One day Lorena came to the work center. She came to do casting for a play that they’re doing called Ways to Paradise. I wasn’t going to do it. No. But there was another person who wanted to go and I helped him with directions to the place where they were doing the casting. And then I got involved. Now I’m involved with Ways to Paradise, about the problems facing migrant workers, explaining who we are, what we’re doing: Yeah, we’re undocumented, we’re from Central America, Mexico … I started thinking about the work, and I really like it. So I stayed. That’s it. There’s not much more to tell.

SFBG I’d like to ask Lorena: How did you become involved in the theater, and how has your relationship with it evolved over the years?

Lorena Moran I would like to tell you the story of Teatro Jornalero, how the project got created. In 2006, Michael John Garcés, the director of Cornerstone Theater, wrote a play called The Illegals. He went and did castings at all the day laborer centers. [Co–artistic director] Juan José [Mangandi] came out of that. He participated in the work, along with other workers from day laborer centers at the national level. And they were invited to a national congress of day laborers. One day they were bored, just hanging out. And Juan José said, “You know what? I have the script of The Illegals. Why don’t we just do a little piece of it and present it to the congress?” It was a marvelous idea.

We have lots of ideas that are marvelous. We need a reason to do it and we also need people to help us. Nothing is possible without that. This was a great idea of Juan José. And we got a lot of help from Michael Garcés and Cornerstone Theater. Roberta Uno of the Ford Foundation gave us our first grant, a big grant of several thousand dollars for two years. And right now, we’re working on a small grant of $25,000 for two years. It’s not much — it’s a big deal to maintain 21 people on $25,000. But it would not have been possible at all if we didn’t have these workers — gardeners, housekeepers, bouncers, day laborers, nurses — they all have stories and voices. And they can educate others, and educate themselves about the rules of this country, the laws, their status as undocumented people.

In 2008, I was invited to participate in a casting for the first company of Teatro Jornalero Sin Fronteras. We were 12 members, two directors. Ethan Sawyer, an American graduate of Northwestern, helped train Juan José, who didn’t know anything about the technical part of theater but had a big spirit for it. They helped us, and the other 12 members of the company.

And that’s how my story starts. I’d had just a year here. I’m from Guatemala. I suffered domestic violence; that’s something I don’t want to remember. They even have my three kids; they’re still there now. But I’m here. And I’m growing a better life. And my dream is that when I’m a citizen I can bring my kids here. But nevertheless, I’ve had five years in this country, and the theater saved my life. And if I’m well, I want my friends to be well, in spite of the traumas, the economic problems. I was this close to getting deported once. I was this close to getting deported once. I was working on a corner with my husband, Xico. I was working gardening, in construction, cleaning houses. I spent five months making six houses. Twelve men, one woman. I was the only woman building houses.

All that showed me the world of day laborers from the roots up. We’d get up at 5:00 in the morning and be standing next to Home Depot. And somebody would drive up and say, “I need somebody,” and we’d run. It was like trying to play the raffle. In my country I’m actually a business administrator. I have a university degree. It’s a totally different life. And there I am, standing on the day laborer corner. I’ve had to clean bathrooms, deal with sexual harassment, I’ve had to clean, and change floors out, and paint — it was a completely different thing for my life. And I realized this is the moment to find a sense of what it’s like to be a migrant. Separated from our families, from our countries; we’re not raking in money, we just want to live with dignity.

So we did a casting. We had some administrative help from Michael John Garcés. And I was named the managing director. It was a whole process. It didn’t happen immediately. But from the beginning I was a part of this group. There’s a moment when you’re present, and there’s a moment when you leave. I don’t know when I’ll leave. But I want people to love this group. We have a voice, and we have a story. We ourselves are part of this story, and we’re writing it.

For today, I’m grateful for my life, and I share with Brent and Amy and their group. I haven’t stop writing, because each day I want to get down every word that drops out of their mouths. For me, it’s part of my learning. That’s what this exchange is all about. We’re training in technical ways with a group that has a lot of similarity with us. They’re helping our community of day laborers and house cleaners. We’re talking. Not in the same idiom, but the same language. And I’m very grateful.

SFGB Can you say a little more about what it’s been like to work with the Imaginists?

LM This is a dream. It’s a dream. To think it all started those years again with Juan José and Sergio in Washington, DC. Juan José Mangandi, the other artistic director, he dreams all the time. He thinks of all these big ideas. For four years we’ve been looking for funds to do this. And we found a grant. And here we are. And we’re dreaming of a second one. We don’t know when or how, but we have a dream, we’re going to keep going, we want to build a network of theaters nationally in the same line as [Teatro Jornalero]. But even so, we have to talk more. This coming together now is a first pass.

We’re just dreaming — some groups in a bus, in a van, connecting with each other from different cities. We’re empowering our voice as immigrants with respect to the larger population of whites, African American, and other groups. This is the story that we have. We’re trying to remove the barriers to our opportunities. It’s huge that we came together.

SFBG What about for the Imaginists?

Amy Pinto For us, the kind of work we’re doing — in bringing Spanish and English together, the issues of the day laborers, and bringing people who are day laborers and professionals together to perform — sometimes the community doesn’t understand, and we’re not always supported. So you [Teatro Jornalero] coming here gives us strength. You teach us how to be strong and to come together to make this kind of work. I think for [Imaginists company members] Zahira [Diaz], and Sergio [Zavala], and Marcela [Mejia], and Gustavo [Servin], who is young, meeting all of you — they see the road then; and it can empower them to take more leadership.

Brent Lindsay It reminds us of why we do theater.

LM I have one question for Amy and Brent. How did it come about that two white people decided to come so close to our community, and do such magic things and help empower us? There’s migrants and Latinos — how did two white people decide to tell our stories, to live our stories?

BL There was a gentleman in the video that you showed. Close to the end, he said, I want to be proud of what I do in life. Like you, Lorena, theater saved me. And it became my religion because it saved me. My investment in theater now is the investment of human beings, what theater can give to others. Because what it did for us, that gift — now we should become its messenger. We have to invite every person into this art form. For the reasons that you’re finding: It heals us. It’s too easy to let fear divide us. We have to worker harder, to overcome fear and come together. Because so much of that fear is based on nothing. It’s nonsense. And the best way we learn that is to do what we’re doing now.

A conversation with co–artistic director Juan José Magandi [translation by Marcela Mejia]

SFBG Can you tell me about Caminos al Paraíso and your part in the production?

Juan José Mangandi As the dramaturg, I try to put the stories together in a cohesive way, drawing from the experience of the actors and my own — as a day laborer, as a community organizer, as an undocumented person. There was a lot of pressure of impose specific themes or stories, but in the end I put in what I felt was the most appropriate for the story as a whole. I was tempted to tell my own personal story, but I tried to tell the story of our community. it’s the first full-length play of Teatro Jornalero since I’ve been working with them, seven years now.

SFBG What was the starting point for this new project?

JJM I’ve worked for many years on behalf of day laborers, and have heard many stories, experiences, tragedies, dreams, songs. So Caminos al Paraíso is the story of the breakdown of connection, of what it feels like for people to lose their home, their town, their country. For example, Chronic Stress Disorder is something that affects many immigrants. Every time you cross a border, and then another, the syndrome grows worse. You don’t get rid of it. It manifests in the way you behave — in anxiety, fear, even the change in the diet has an effect, in addition to the intrinsic dangers that a journey like that implies.

So we speak about these things, so people know what happens when one cross the border, including the abuses on the Mexican side of the border. Everybody talks about the US and the racism and the discrimination of an imperialistic government, but what happens when our own people are the ones that are doing the discriminating? So the governments from Mexico and Central American countries say they want to protect the rights of our emigrants and yet they are often the first ones to commit abuses. So it’s a critique of the economic, political, and social conditions. It’s an industry, an industry of immigrants, not only here but there as well, where for the ones that benefit — the government, the traffickers, the narcos, everybody — it’s a business, it creates a lot of employment for people.

So there are a lot of tragic events that immigrants experience before they arrive in the US. And then what happens when we arrive in “paradise”? That will be the second half, and that’s a totally different story. We start to mix with other races, and we start to change. I mentioned already the diet, but also the culture, the values, the sense of belonging to a community, not necessarily a country. And chronic health problems can ensue. Many become bipolar or diabetic, suffer from high cholesterol, high blood pressure. It’s like the body is not prepared for all of this processed food. It’s a big shock physically, in addition to all the other aspects impacting the humanity of the immigrant.

We are escaping because we are old, victims of the corruption, the lack of opportunities. But we come here and there are no jobs really, and we don’t have a social identity — just the paper itself makes such a difference. It’s like being invisible. Besides doing dangerous work, we are also breaking with our cultures, with our identities, who we were and where we came from. Some people get really uptight about clinging to their past identities. It can become a big obstacle to making bridges to connection with each other, to understand each other.

SFBG Do you see the theater you’re making as a means of helping forge a new culture, bridging those divides?

JJM I think that the theater is a weapon of social struggle and transformation—not only for the people that are out in the audience but also for the actors themselves. The government teaches us about political borders, and then the poverty and the ignorance help us create another border, another barrier. We want to be different, we want to be better than the other, we want to separate form each other—a Salvadoran has to be better than a Mexican, a Mexican has to be better than a Guatemalan, and so on. For me, in my experience, the great problem is, and my big question is: Why can’t we integrate? This is what Teatro Jornalero is searching and striving for, to break these separations. We’ve had people from Cuba, Mexico, Salvador, Guatemala… Sometimes it gets heavy between the actors. There’s an inner racism. All of these themes that hurt so much, that we don’t want to talk about, are in Caminos al Paraíso. But then there is also a message for the community. That we should get ready to integrate. That we like this country. That we have adopted it as our own. Now we want them to adopt us as well, as members, and let us taste the good of this country so we can practice compassion for the ones that come after us.