The first SF Sketchfest, in 2002, was a good excuse to find a stage and some quality time for its organizers’ own sketch comedy troupe, Totally False People, but it has since become an annual comedy conclave of the first order. SF Sketchfest founders David Owen, Cole Stratton, and Janet Varney talk about the growth and philosophy of their annual comedy extravaganza and the humble beginnings that gave it rise.

San Francisco Bay Guardian Is SF Sketchfest a full time job by now?

David Owen Yeah, I think it is. It definitely gets more intense a few months out, but we’re always working on it, we’re always percolating ideas, as well as trying to do events throughout the year. We had a presence at Outside Lands this past year. We’re always trying to do stuff. But this time of year especially, from fall on, is beyond full-time for us.

SFBG Has it had to change a lot structurally as it has grown, or are you still pretty much running it as you always have?

Janet Varney We earned some pretty simple lessons along the way, including Cole, Dave, and I not driving every single headliner to and from the airport, and sell tickets at the box office, and sell our concessions, which is what we were doing the first few years.

DO The growth has been gradual. Over 12 years it’s been a little bit like a snowball, each year we add a little bit more. There are more performers, more shows, there’s more logistics, more general stuff to deal with. Twelve years in, it’s grown to a place none of us ever imagined. We never imagined we’d even get to the second or third year and have one Kid in the Hall, let alone have all the Kids in the Hall and all these comedy legends, who are our heroes. You said humble beginnings, that’s absolutely right. It was a local festival, just for us to perform at, and 12 years later we’re still surprised that it’s so many shows, with so many people that we like.

SFBG Have you gained a new perspective on comedy that you didn’t have before?

DO When we started, we were just fresh out of college and we wanted to write our stuff and perform it. Cole is still performing, he can speak to that, but from my point of view, just seeing it as a producer now, I think our first couple of years we thought, “Oh, there might be an audience in the Bay Area for this kind of comedy.” And now it’s clear that there is. There’s a big appetite for it, because we keep adding shows and people keep coming.

We’ve learned that laughter is important, that people really want to get out of the house, and in the dead of winter, to come to a comedy club or a theater and experience something with a group of people where they’re all laughing. There’s nothing else like that. I have to say that I’ve really learned that getting out and laughing is important for people. It’s a fun thing that people like to do. Hopefully we’re providing something that’s unique and different from other festivals or other shows.

JV We’re so proud of San Francisco and the way San Francisco receives the comedy we bring to the table. Cole and I live in Los Angeles now, Dave is still in the city, but we all have this fierce love of San Francisco. It’s such a wonderful way for us to interact with the people in the city that we love. We feel like they back us up every year by being the most savvy, enthusiastic, great, smart audiences. That’s why performers come back here year after year as well, they love performing for San Francisco audiences. The festival couldn’t be what it is if we didn’t have those kind of people, as Dave said, showing up to laugh together.

Cole Stratton What made our festival a little different form the start was, you know, we started as performers, we came at it from that vantage point — it’s about the comedy; it’s about making it as artist and performer friendly as we can. I think why a lot of people embraced it early on was that it wasn’t about doing work that there’s a lot of pressure on. It was come have fun with each other, try some stuff — let’s have fun and really celebrate comedy.

The audiences in the Bay Area totally get that too. There’s been this tremendous energy at all our shows. Everyone feels a part of something that’s really fun, unique, and different. That’s been the spirit of the festival year after year.

SFBG Is the social or political significance of comedy something you guys think about?

JV Absolutely. I think the three of us respond to comedians who are brave in that way. Who are willing to hold a mirror up, to what happens to us in society and what happens to us as humans, but who are willing to get really personal. We love silly comedy, comedy that isn’t necessarily about anything; we love the absurd, we love lighthearted, sort of childlike comedy. But we also respond really strongly to people who are unafraid to say, hey, this is me, are you like this? This is ridiculous.

Obviously those comedians become beloved because they are humbling themselves and they’re also reminding everybody in the audience that it’s ok to be a human being.

DO It can be cathartic, to come away from a show where someone has talked about mortality or heartbreak or environmental problems in the world — and all the things that trouble us — it can be cathartic to come from a comedy show and you’ve laughed about it, you’ve thought about it, you’ve learned a little bit about it. But I want to add that in our programming there isn’t an agenda — like, ok, we need to have ten socially conscious comedians, and we need to have five absurd ones.

Our only agenda is: Does it make the three of us laugh? That’s how we decide what’s going to be in the festival. We don’t spend a whole lot of time thinking about what’s going to make the most number of people laugh? We just hope people like our taste. Our taste, as Janet said, it really runs the gamut from infantile, silly, ridiculous stuff, stupid stuff, all the way up to really smart, socially aware, critical comedy. We like all of that stuff. As long as it’s funny. That’s what matters.

SFBG Are people approaching you more than the other way around at this point?

JV It’s still both. We’re very lucky because we’ve had wonderful experiences with people we sort of chased down and invited in the beginning. We have a lot of returning guests year after year that we’re still excited to welcome back, and audiences are excited about. People like David Wain, who want to come here year after year and are always thinking ahead as to what kind of new, interesting show they can bring to the table so that they’re keeping it fresh but still returning to the festival multiple times.

We still have our wish list. We still have our people that we like to chase down, and cross our fingers and hope for the best. The comedy community, luckily it can be kind of close. We’re really lucky in that we have this amazing pool of references. But we still write letters with our fingers crossed, and hope for the best, as much as people reach out to us and ask to come back, or we have agents calling us whereas before we might not get our phone calls returned.

SFBG The podcast has really become a major new platform for comedy, as the lineup this year reflects. Are you searching out new outlets as well as new shows?

DO The three of us all spend a lot of time scouting and looking around and trying to keep our finger on the pulse, just seeing as much as we can, whether it’s in person or online. We try to stay clicked in to what’s going on out there. But we’re also looking for something that’s new. What can we do that is a totally new format? We love standup and sketch and improv and film stuff, but we also like doing things like game shows, or live talk shows.

This year we have a walking tour of the Asian Art Museum led by Canadians, or we have a show that mixes comedians and musicians, or Reggie Watts with a dance troupe. We try to see how we can do something at this festival that you’re really not going to see anywhere else. Not just something that’s on tour or that you’ve seen on TV. What can we debut at the festival, premiere as a brand new idea or a brand new concept or format? Those are things we think about and try to pursue.

SFBG Is the tour of the Asian Art Museum by Canadians an example of an original idea?

DO That one, no. That was a show that existed in New York. They did it at the Metropolitan. They’re going to be doing it in San Francisco for the first time, but that specific show was not our idea. We do come up with concepts that we think might be good for somebody, and we’ll pitch them, and if the artist is into it then it might come to fruition.

[For example,] we’re doing a show called Yacht Rock Heroes. Mustache Harbor is this amazing San Francisco band that does covers of ’70s and ’80s soft rock classics, Toto and Hall & Oates and those kinds of things. We thought it would be fun to have comedians come out and cover the song with the band as kind of a mash up. Mustache Harbor liked the idea, and we found comedians who were into it, so we kind of put it together from there.

SFBG How did you all first meet?

DO Cole and I were in the same floor in the dorms at SF State as freshmen. He was on one side and I was on the other. Everyone else on the floor was either a jock or a party animal…

JV [Laughing] That’s the first time I’ve heard someone say “party animal” in a serious way. I just love that that happened.

DO Yeah. There was a nerd on one side, and a nerd on the other. We were both into comedy and movies and music. And everyone else was into, like, swimming.

CS I lived in the dorms for like a year or whatever. I remember it was time to push on when — there was one communal restroom and I had to walk all the way down to it in the middle of the night, and there was a party going on, and I looked down. Someone had thrown a starfish into the hall. Like pulled it out of an aquarium and threw it into the hall. I was like, “Ok, someone just murdered a starfish on my floor. I think it’s time to go anywhere else.”

DO And then we became roommates, and we were working at the same video store and were roommates for, god, how many years? Three or four years. Five maybe. And then Janet — Janet, where did we first meet, at the Castro Theatre?

JV Yeah, I think we met at the Talking Heads show, Stop Making Sense. It was the anniversary screening. Actually, we love this story because Dave and I met and — Cole, you were there too, yeah? I don’t know why I only remember Dave. Cole, we met before this interview, right? We all went to an anniversary screening of Stop Making Sense with David Byrne in attendance. He actually was sitting right in front of us. We love that everything came full circle, and that we ended up doing a screening of True Stories at the Castro Theatre with David Byrne.

DO Cole and I had a mutual friend — this didn’t happen right away but not long after we all met, this guy wanted to start a sketch comedy group. We were all theater and film majors, and we were putting on plays or making little films. And this guy wanted to start in comedy. We were all into it. There was about maybe six or seven of us who started meeting up, trying to write sketches. One by one people sort of fell away, and then there was four, the three of us and Gabriel Diani. And that’s how Totally False People started.

SFBG Where was your first gig? Where would you perform at the beginning?

JV We started doing shorts at a couple of the comedy clubs, and I think, was Rooster T. Feathers the first gig?

CS That was the very first show, Rooster T. Feathers in, Sunnyvale? Yeah. Our thinking was let’s make sure we’re at least 45 minutes outside the city limits if it doesn’t go well.

JV We went up on a stand-up, kind of a showcase night. We did a few different shows there. On one occasion someone called and left a voicemail after we performed saying that they didn’t enjoy our, quote, play-acting. We were trying to do sketch on this standup comedy stage and apparently people did not know what to do with us. We were going up there with like costumes and wigs…

DO That was our first review: “Did not enjoy the play-acting.”

CS And we thought, let’s start a festival!

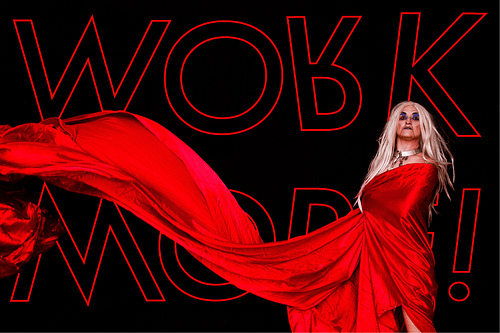

SF Sketchfest: The San Francisco Comedy Festival

Jan 24-Feb 10, prices vary

Various venues, SF

www.sfsketchfest.com