arts@sfbg.com

FALL ARTS From retrospectives and installations tied to big names, to smaller but no less arresting gallery exhibitions, this fall’s visual art offerings will have a lot to say about political bodies, politicized bodies, and the body politic. It’s heartening that the “blockbuster” shows listed here by and large focus on artists whose work doesn’t shy away from politics or political activism. After a summer in which there was a palpable uptick in public conversations about the US’s role in humanitarian injustices — both home and abroad — I hope the following exhibitions encourage people to keep talking.

“Keith Haring: The Political Line”

de Young Museum, Nov. 8, 2014–Feb. 16, 2015

The posthumous ubiquity of Keith Haring’s art (on coffee mugs, T-shirts, postcards) has overshadowed the fact that he made work that was as committedly political as it was populist. His stances on antinuclear proliferation, apartheid, and the survival of sexual communities in the face of the AIDS epidemic were as clear as his trademark figures. This first major West Coast Haring show in over two decades is more importantly the first to explicitly focus on the political dimension of his work. https://deyoung.famsf.org

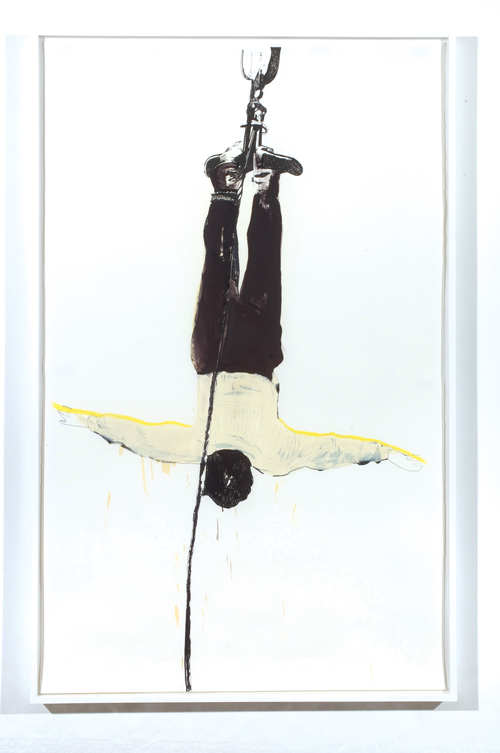

“@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz Island”

Sept. 27, 2014-April 26, 2015

The Chinese dissident artist’s installation on Alcatraz via the FOR-SITE Foundation has been greeted with equal parts hype and skepticism. Working remotely from his studio with a team that includes collaborators from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, Ai has created new sculpture, sound, and mixed media works for four locations on the former federal penitentiary grounds (three of which are usually off-limits to the public). How these pieces will put the artist’s own experiences of detainment and censorship in conversation with the site’s history of discipline and insurrection remains to be seen. Here’s to hoping for as much heat as there is light. www.for-site.org/project/ai-weiwei-alcatraz

“American Wonder: Folk Art from the Collection”

Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Oct. 1-Dec. 21

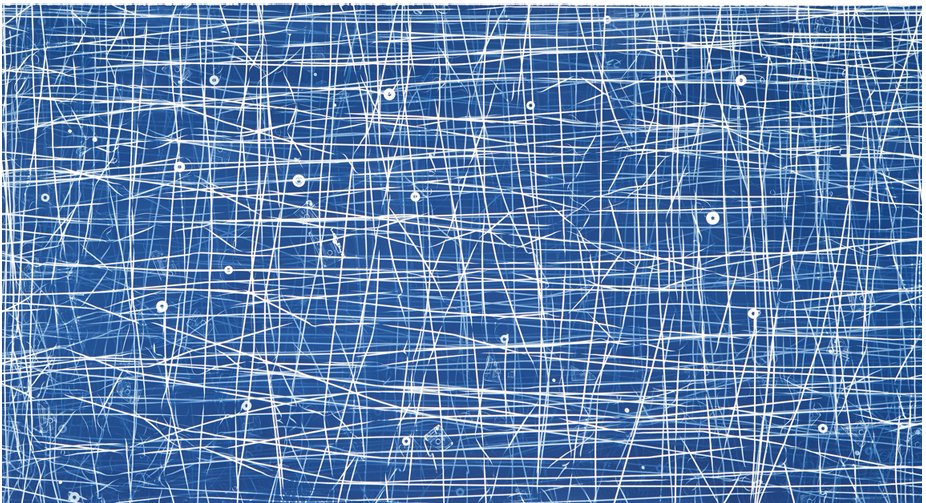

John Zurier/MATRIX 255

Sept. 12-Dec. 21

On paper, “early American folk art” as the subject for an exhibition might sound dry as toast. But a lot happened between the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 to the onset of the Civil War in 1861, the period during which the portraits, landscapes, commemorative mourning pictures, weather vanes, and decorative sculptures assembled here (and all from the BAM/PFA collection) were made. These artifacts of national self-fashioning reflect that history but also the quotidian aspects of daily life which often get left out of its telling. Also on view will be local Zurier’s first solo show at the museum, which features luminous, abstract paintings and watercolors inspired by his time in Iceland. www.bampfa.berkeley.edu

“Nicolas Lobo: D.O.W.”

Gallery Wendi Norris, Sept. 4-Nov. 1

Transforming chemical elements into contemplative sculptural pieces is the MO of interdisciplinary artist Lobo for his first San Francisco solo show. Previously working with sound in varying capacities, he has now turned to food science, isolating the chemical substrates of consumer goods such as doughnut frosting and cough syrup, and incorporating them into napalm and Play-Doh structures that resemble day-glo colored Song dynasty scholar stones. Toxicity never looked so enticing. www.gallerywendinorris.com

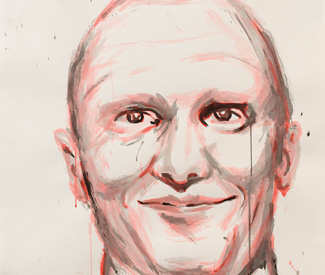

Kota Ezawa

Haines Gallery, Nov. 6-Dec. 20

Throughout his career, Kota Ezawa has rendered iconic images as disparate as Patty Hearst and the SLA robbing the Hibernia Bank and Nan Goldin photographs in a clean, simple style reminiscent of cartoons. The result is at once highly personal and aesthetically flattening, locating Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” outside of the event photographed and in the photograph’s broader circulation across time. This collection of new work should provide another chapter in his ever-evolving history of the medium. www.hainesgallery.com

“Songs and Sorrows: Días de los Muertos 20th Anniversary”

Oakland Museum of California, Oct. 8, 2014-Jan. 4, 2015

While the popularity of the Mission’s annual Días de los Muertos celebration grows in tandem with the dislocation of the community that originated it, Oakland Museum of California’s 20th anniversary celebration grounds the holiday in some much-needed historical perspective, while showcasing Latino and Latina artists who continue to innovate on the traditions and aesthetics the celebration has inspired. www.museumca.org

“Something Completely Different”

City Limits, Aug. 30-Sept. 13

You have to act fast on this one. If you want to see something completely new, head to this group show at one of Oakland’s strongest exhibition spaces. For this salon-style collection, each of the 60 participating artists was asked to go outside his or her comfort zone to create a piece that was truly new. The opening reception Sept. 5 doubles as a gallery fundraiser, so now is you chance to pick up something by one of the Bay Area’s best and brightest. http://citylimitsgallery.com *