joe@sfbg.com

Schools of suit-clad professionals stream up city sidewalks in San Francisco’s Financial District during the typical morning migration to the office. Near the intersection of Sutter and Montgomery streets, one line of immigrant workers stands still as they wait to submit paperwork in hopes of permanently joining the commuting throngs.

Cox & Kings Global Services, where documents of the Bay Area’s new wave of workers are processed and filed, has a queue stretching down the block to a nearby coffee shop most mornings. Workers from India go here to submit their visas, and their numbers have exploded lately.

As the greater Bay Area’s technology sector has boomed, so has its Indian population. This influx is linked to tech’s practice of employing foreign-born workers, mostly from India and China, using H-1B work visas that are usually valid for six years with the possibility of extensions and eventually citizenship.

“You’re seeing this across the US as tech aggressively pursues immigrants to work here,” Todd Schulte, executive director of FWD.us, told the Bay Guardian. “You even see this in the Bay Area.”

FWD.us advocates for immigration reform on behalf of the tech industry to make it easier for employers to bring foreign workers into the US. It was created by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg as his first foray into political lobbying. The move has led skeptics to ask an age-old question with a new spin: Are low-cost foreign workers depressing American workers’ wages? Are they occupying jobs an American labor force could have instead?

Although immigration reform is high on the list of priorities for tech companies, they’re spearheading ways to widen the temporary worker visa program without addressing the complicated issues raised by importing more tech-trained workers from lower-wage countries.

A foreign worker in the tech industry certainly does not suffer the same instability as a low-wage immigrant employee who lacks higher education and technical training. But studies show that the pathway to citizenship created by the specialized H-1B workers’ visa program isn’t guaranteed, presenting challenges for all involved.

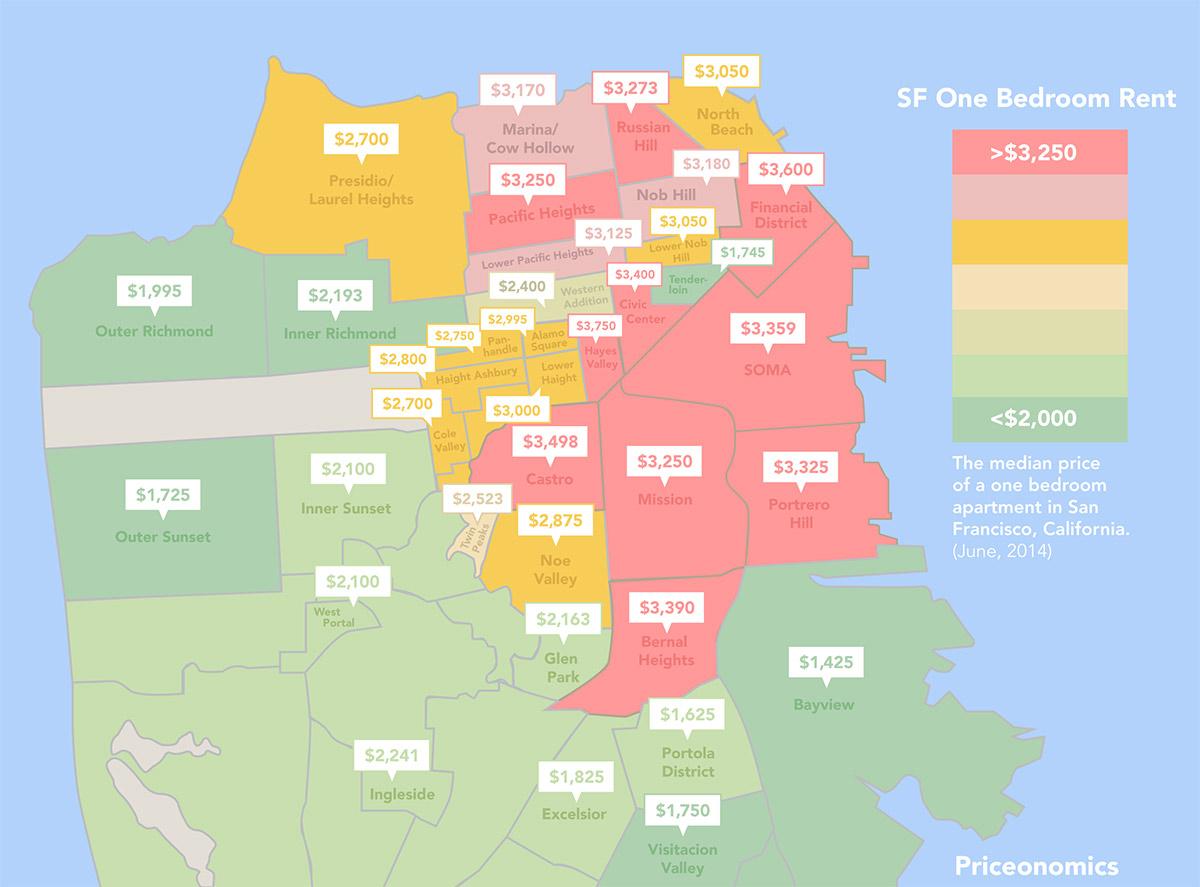

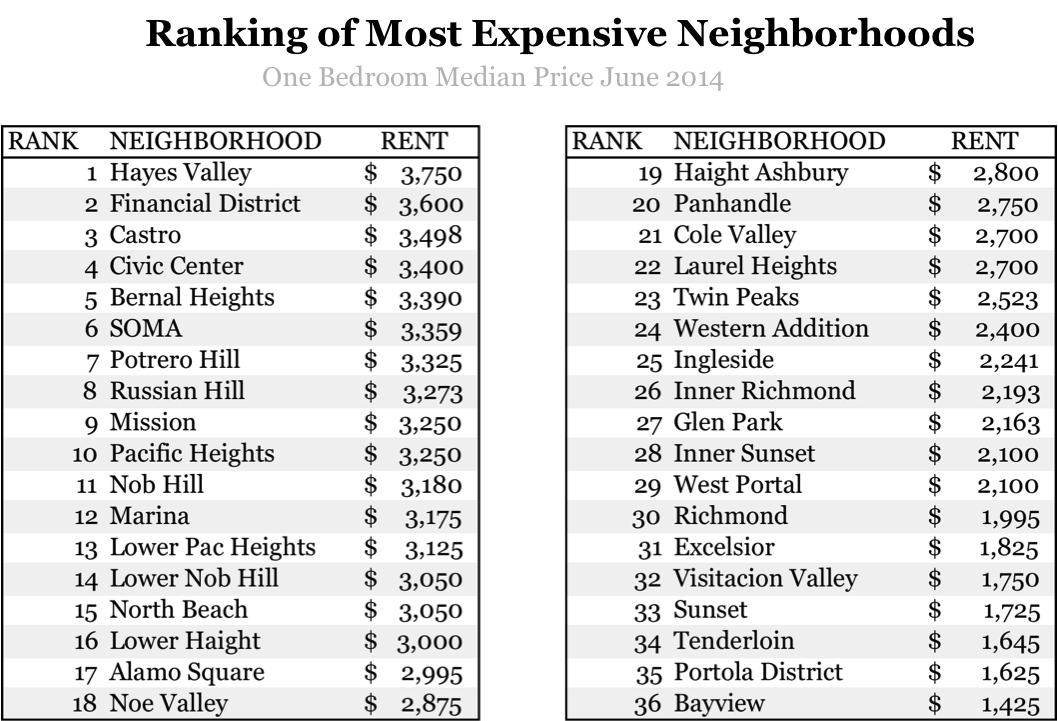

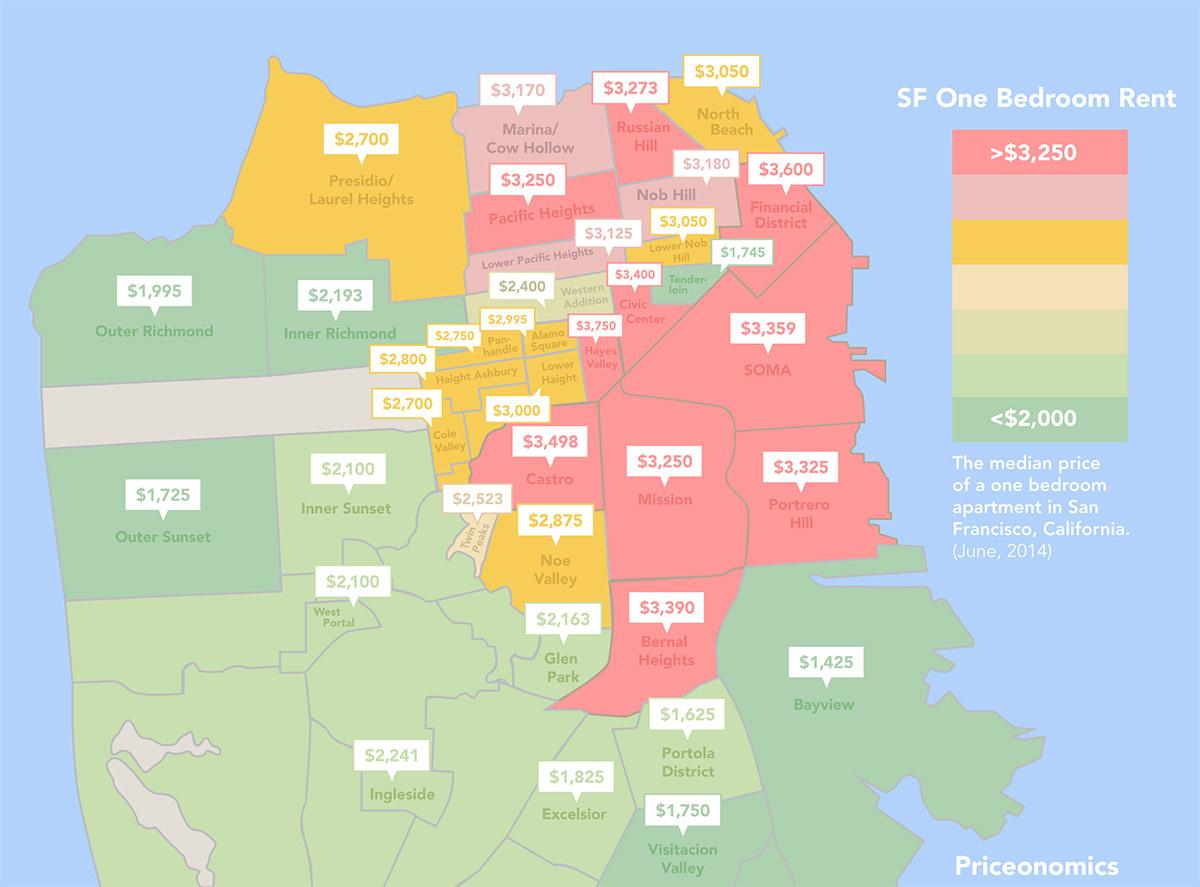

Click map for a larger version.

H-1B visas are technically known as “nonimmigrant visas,” indicating the workers aren’t expected to remain here permanently. So while American citizens are made to compete for jobs with those foreign workers who usually earn less, nonimmigrant workers encounter high barriers to obtaining the security of citizenship.

For now, the tech companies gaining low-cost workers seem to be the main beneficiaries of this skewed system.

GOLDEN HANDCUFFS

First came the boom. Tech jobs were less than 1 percent of San Francisco private sector employment in 1990, but now make up nearly 8 percent of the city’s private sector jobs, according to research by urban development nonprofit SPUR. The tech boom coincided with a population boom of Indian and Chinese workers, temporary visa holders who may or may not seek permanent US citizenship.

San Francisco saw more than 8,000 nonimmigrant visa applications in the 2012-13 filing year, according to MyVisaJobs.com, which assembles reports on nonimmigrant visas. Employers in the Bay Area as a whole, including San Francisco and Silicon Valley, filed over 29,000 applications for H-1B visa holders. The majority of those workers are from India, and to a lesser extent, China, according to data from the US Department of Consular Affairs.

The H-1B is the golden ticket for foreign workers to work in the US, and the center of much of the controversy. An employer sponsors the worker under an H-1B, tying that workers’ ability to live in the US to the employer. More importantly, the workers’ permanent residence process — and becoming a US citizen — is also tied to that employer.

So not only is nonimmigrant workers’ presence in the US in the hands of the people signing their paychecks, but so is their potential citizenship, creating an imbalance of power.

“[Workers] have the legal right to leave the employer, but don’t dare do so because they would have to start the very lengthy green card process all over again,” Norm Matloff, a UC Davis professor and researcher with the Economic Policy Institute, told the Guardian. “Note that we’re talking about the mainstream American companies and startups.”

Standing in line back at Cox & Kings on Sutter, the Guardian spent a few days speaking to various Indian technology workers as they finished filing their paperwork. None were willing to speak on the record due to their tenuous citizenship status, fearing employer reprisal. But these workers did confirm to the Guardian that their employers effectively hold a huge hammer over their heads: deportation.

What do employers have to gain with this sizable leverage? A paper by Ron Hira, “Bridge to Immigration or Cheap Temporary Labor?” catalogued systemic underpayment of foreign workers, sometimes by as much as 25 percent less than their US counterparts. Of course, the pay is handsome in Silicon Valley, even when taking a hit compared to US citizen peers. The average salary of an H-1B visa worker is $99,000, according to MyVisaJobs.com.

“H-1B rules place most of the power in the hands of the employer at the expense of the guest worker,” Hira wrote, “creating sizeable opportunities for exploitation … many have described this employment relationship as indentured servitude.”

This is done legally, the study found, because of substantial loopholes in federal labor and guest worker laws.

We asked Matloff if it was possible to measure the impact of depressed nonimmigrant Silicon Valley workers’ wages on the overall wages of the Bay Area, and we were told this would be “very hard to quantify.” But his research leads him to believe tech worker wages in the Bay Area are depressed as a result of nonimmigrant visas.

The nonimmigrant visa workers wear what Matloff calls golden handcuffs: under the thumb of their employers, but perhaps comfortably so. And all of this would be worth it for them, if the visa-holders could stay in the United States.

Uncritically, the tech industry is going to great lengths to defend its ability to hire nonimmigrant workers, who are cheaper than their citizen counterparts.

QUESTIONABLE ADVOCACY

Rishi Misra came to the US for college, and pushed his way through startups and biotechnology companies. Now he works at Archimedes Clinical Analytics, located in the South of Market area. He still is not, as of yet, a US citizen.

“My wait to become a US permanent resident continues, more than 16 years after I first came to this country as an undergraduate student,” Misra wrote in a FWD.us testimonial, “more than 10 years after I started working, paying taxes, and more recently, helping build start-ups that are making a positive impact on the US economy and society.”

Misra’s struggle for citizenship mirrors Hira’s study on H-1B visa holders. “A nonimmigrant visa can be an important first step toward permanent residence for many skilled foreign workers,” Hira wrote. “But most never make it.”

The federal government doesn’t keep explicit conversion numbers of temporary work visas to permanent residency, we learned after contacting the Department of Labor and the USCIS. But Hira’s study estimates that only 1-5 percent of H-1B visa holding temporary workers gain citizenship status.

To be sure, there are some exceptions in the tech community. Google and Microsoft historically have sought to assist most of their immigrant employees in gaining full residency, while Cisco and others have only converted about a quarter.

But many tech companies outsource work to offshore firms, often based in India, and federal data shows they employ the most H-1B visa holders, and offer citizenship the least often. Still, as they also fight for permanent residency, advocacy groups focus on bringing in H-1B workers in greater numbers.

According to the government transparency group Open Secrets, FWD.us put as much as $900,000 to the cause of trying to open the door for high-talent tech workers like Misra, here in San Francisco, but not necessarily towards reforming workplace rights.

The tech companies claim there’s a technology employee shortage, but Matloff and the Economic Policy Institute strongly disagree, saying no study that wasn’t sponsored by the tech industry has ever demonstrated a US tech worker shortage. But what can’t be argued is the swelling number of nonimmigrant workers vying for a spot in the US. The cap for new nonimmigrant visas is currently set at 65,000 by the federal government. In only the past two years, applications for those slots filled up in less than five days from the filing date.

It is on behalf of tech companies that want to hire those nonimmigrant workers that FWD.us brought thousands of dollars to bear against key progressive causes.

FWD.us, led by Zuckerberg and a cadre of tech cohorts, has come under fire for much of its advocacy. Notably, the group supported national Republicans’ efforts to build the Keystone XL pipeline, supplying them with ample support for TV ads.

The backlash from environmental groups, many of whom hail from the Bay Area, had the tech community and other supporters of FWD.us running for the hills.

“As a startup founder, former Senatorial intern, and director of an amateur documentary about racial inequality in public schools, I cannot tell you how excited I was to hear about Mark Zuckerberg’s FWD.us,” wrote Branch co-founder and CEO Josh Miller, in an editorial on Buzzfeed. “In service of noble causes, FWD.us is employing questionable lobbying techniques, misleading supporters, and not being transparent about the underlying values and long-term intentions of the organization.”

If ever there was a cause to unite tech workers and other progressive San Franciscans, it would be decrying Zuckerberg and FWD.us’ backing of massive oil pipelines on US soil. Many liberal political groups pulled their ads from Facebook after the Keystone XL ads aired.

Moving forward, Todd Schulte said FWD.us would need to change its strategies, after being handed decisive losses in Congress by Republicans blocking immigration reform. “We’re going to keep pushing,” Schulte told us. “One thing that we’ll do better is to make a broader coalition.”

But rules pertaining to depressing nonimmigrant worker wages aren’t on their agenda, and Schulte said this was not a problem in the tech industry. He claimed the cost would be too great to bring workers in from overseas and train them, simply to save a few dollars.

The workers we talked to told a different story.

IN LIMBO

The Guardian went back to the line at Cox & Kings, intent to check out Schulte’s stories of the glamour of nonimmigrant visa holders working in the tech industry. We asked a few folks in line what working for US tech companies under a nonimmigrant visa was like.

One man, clad in a lime green shirt with a messenger bag slung over his shoulder, had much to say. Not wanting to be named, again due to tenuous citizenship status, he wagged his finger in our face strongly with each point. Firstly, coming to the Bay Area for some Indians is a no-brainer, he said.

“The typical guy loves his vegetarian food and loves his [Hindu] temple,” the man told us. “They realize the Bay Area is not so different than home.”

But the man, who described himself as more affluent than the average nonimmigrant worker here (“My family owns temples in Bombay, plural!”), said he was often treated like a second class citizen in the US. He worked for tech companies in the past, and his brother works for a prominent and long-standing Bay Area tech company. His nephew works for a prominent Seattle-based tech company.

“There and [in India] it’s like a fucking sweatshop,” he said. “Some come here and they’re cheated!”

He was referring to the wage-fixing some US companies engage in. Matloff told us those most vulnerable to this practice were those seeking US citizenship. “The handcuffing is clearest in the case of those H-1Bs who are simultaneously being sponsored by their employers for green cards,” he said.

Those who did speak on the record about wage fixing were those who already achieved the dream: former H-1B workers who are now US citizens.

For ten years Manish Champsee was on the Board of Directors at WalkSF, a pedestrian advocacy group in the city. In his day job, he owns a web development company, after a long stint as an H-1B visa nonimmigrant tech worker.

A Canadian citizen, Champsee first flirted with computers in the fourth grade. The young Champsee taught himself programming in BASIC, a coding language. In college he strayed a bit, learning to be an actuary, but soon realized technology was his passion.

Ten years ago, he came to San Francisco on an H-1B as a systems programmer analyst, and experienced the golden handcuffs firsthand. At first, he didn’t realize the precarious position he was in, until he unwittingly angered one of his bosses.

“I started off thinking about it once in awhile. At a certain point I started thinking about it a lot more,” Champsee said. “I pissed off the wrong person in the company. It was a game of chicken.”

All of a sudden, the threat of restarting the citizenship process, or even deportation, entered his workday thoughts. His employers’ power over his future was suddenly very real.

“They can hold it over your head,” he said.

But he stuck it out. The day Champsee realized he wanted to be a US citizen, he was sitting in the natural beauty of Yosemite.

“I was camping a few days and did some hikes with a friend,” he said, and started thinking about all San Francisco had to offer. The walkability, the natural beauty, the charming local mom and pop stores, the food, and the people. “It all came together there.”

Champsee made it, and gained his citizenship in 2012. But despite all the tradeoffs the US has made in hiring swelling numbers of temporary workers, fewer are able to follow his path into citizenship.