arts@sfbg.com

YEAR IN VISUAL ART Maybe it’s the Mayan calendar thing. Large cycles and turnings, old giving way to new, and all that. But in thinking about 2012, I can’t help but think about big seismic shifts and changes to infrastructure that are moving large pieces of the art world around, setting adrift transformations that won’t settle down for some time.

So, at year’s end I’ve written here something more like a love letter of hopes and apprehensions for my chosen profession as it evolves into whatever comes next. For to be sure, 2012 saw the structures of the art world (whatever that term means to you) a-changing.

From the viewpoint of commerce, never before has the term “art market” seemed more apt, as the art fair circuit has seized firm control over art buying, in environments that feel much more like a Tangier spice bazaar than any kind of dispassionate white-walled arena for ideas.

But forget that old definition for an art gallery anyway. The new one for 2012 and beyond is this: a storefront for itinerant consultancies who are measuring their time until touching down in the next art fair booth.

Given that, it’s completely logical, and also disheartening, that larger numbers of Bay Area galleries truncated their hours in 2012. Why be open for more than 10 or 15 hours a week? As one gallerist told me this year, “The storefront is just for hospitality. We don’t really sell anything out of here.” Indeed, increasingly Bay Area galleries sell on the road in Miami, New York, Basel, Hong Kong, or somewhere else at one of the large art-fair conglomerations that now define the selling calendar.

For people like me, for whom wandering in and out of galleries is necessary for our peace of mind, this emerging scenario really bites. The nascent, creeping practice of keeping gallery hours only on Saturday, possibly Sunday with maybe another weekday thrown in (and you know who you are) does nothing to bridge the widening gap between the commonly held outsider perception that galleries are not for ordinary people and the dawning insider suspicion that, well, maybe galleries are not for art people either.

There has always been a divide between inside and outside the art world, but that has largely been a matter of self-identification. The insiders have always been the weirdos who bothered to care, who got geeky about the poetic language of objects and situations, tracking artists and galleries the way other people track chefs and restaurateurs. What worries me is that us weirdos are losing bandwidth in our own scene; until recently “insider” has included the art-viewing-and-talking public, and not just the art-buying class. The forming idea of what an art constituency is has rapidly shifted, and though I’m not exactly on the same page as ex-critic Dave Hickey, who very publicly “quit” the art world this year (with statements like “Art editors and critics — people like me — have become a courtier class. All we do is wander around the palace and advise very rich people. It’s not worth my time.”), I get where he’s coming from.

If the work is increasingly being shown and promoted elsewhere along a rarified travel route, what recourse are the rest of us empty-pocketed onlookers supposed to have? But all signs point to this continuing and accelerating. In 2013 we’ll see the market further consolidate around global cities and travel plans, and for local galleries, “risk-taking” will increasingly have less to do with ambitious, place-aware programming and more with stretching budgets and maximizing production to keep pace with the expanding endless summer of art fairs.

But gathering together seems to present its own risks, too. Superstorm Sandy served an ominous warning about the geographic and physical contingency of the architectures where art is both sold and guarded. This year we witnessed the mass wipeout of both artworks and small galleries caused by a single (albeit badass) storm, literally swamping the world’s highest concentration of art dealers and contemporary artworks in the hemisphere’s most important art neighborhood. Many of those galleries and artworks will not resurface. For every one David Zwirner, with his stable of well-insured, blue chip artworks, there are a dozen small galleries each with emerging artists who just lost entire seasons of work and rent.

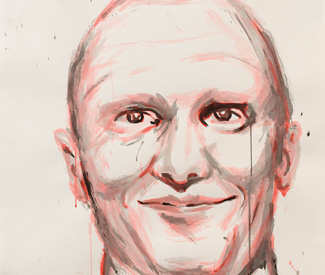

And I can’t not mention the January suicide of Mike Kelley, a hero to me and most artists I know. His death was a somber reminder that the art world is still inhabited by, and is shelter for, troubled hearts who sometimes can’t outrun their own demons, no matter how successful or beloved they become.

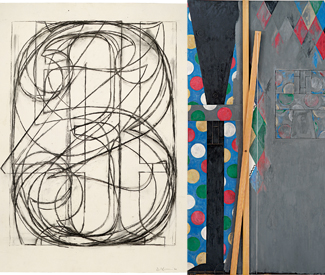

Yet there’s hope too. I saw some great shows this year, in museums, in galleries and, yes, at Burning Man, where Matthew Schultz’ breathtaking Pier 2, a 250-foot, full-size pier complete with shipwrecked Spanish galleon, hit the perfect note of surreality and absolute joy. Both the Jean Paul Gaultier show at the de Young and Cindy Sherman show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art reminded us that institutions can dazzle when they set their minds to it, and Ben Kinmont at SFMOMA demonstrated that even if you’re stuffed into the mezzanine reading room, you can still pack a conceptual wallop. I also loved Mark Benson’s show at Ever Gold, Liam Everett at Altman Siegel, and Brent Green at Steven Wolf, to name just a few.

Where art making intersects the public there were bright spots, too. I mean, sure it’s a publicity gimmick that’s in practice all over the country, but somehow Oakland Art Murmur became a thing this year, an authentically energetic collection point that now draws thousands of people to Uptown Oakland each month. And tech continues to make inroads into the decidedly old school art machine: Kickstarter, Indiegogo, Paddle8, Art.sy, and a slew of other web tools made following, researching, and funding creative projects more democratically accessible. Indeed, I’m increasingly hopeful that from tech somewhere we’ll see an antidote to the increasingly oligarchical practices that sustain the current art market. *