HAIRY EYEBALL Weds/2 marks the first citywide general strike in our country since 1946. Spearheaded by Occupy Oakland in the wake of the Oakland Police’s grossly excessive use of force against protestors last week, the strike is further proof that the only definitive thing one can say about the Occupy movement is that it is growing at a remarkable pace.

Whether this growth will result in greater political traction, rather than merely prompt further sympathy or ridicule from politicians and the media alike, remains to be seen. Then again, one metric of political traction for the Occupy movement is simply endurance, measured by present bodies. As Lili Loofbourow recently wrote in an on-the-ground report on Occupy Oakland for website The Awl, “technology tilts the political machine so that only that which is public matters.” And despite the Occupy movement’s necessary imperfections, there is no more direct and immediate way of being public than showing up and speaking out.

What gets broadcast and what gets heard beyond the encampments is another matter. Even with the tools of social media at the Occupiers’ disposal, can the movement’s horizontal, leaderless structure effectively amplifying the voices of “the 99%” without resulting in an echo chamber? And if that is what’s being perceived, both on the ground and in the national conversation, is that necessarily a sign of the movement’s failure or merely a testament to its vibrancy?

A variation on these questions of mediums and messages is at the heart of Geof Oppenheimer’s intellectually bracing and formally daring show at Ratio 3, Inside Us All There Is A Part That Would Like to Burn Down Our Own House, which although not explicitly about current events, uncannily resonates with them. The work in Inside Us formally traces the fluctuating state of the body politic by zeroing in on moments of stress in which civic faith breaks down or flares up, whether due to admissions of failure on the part if its appointed leaders or from internal combustion.

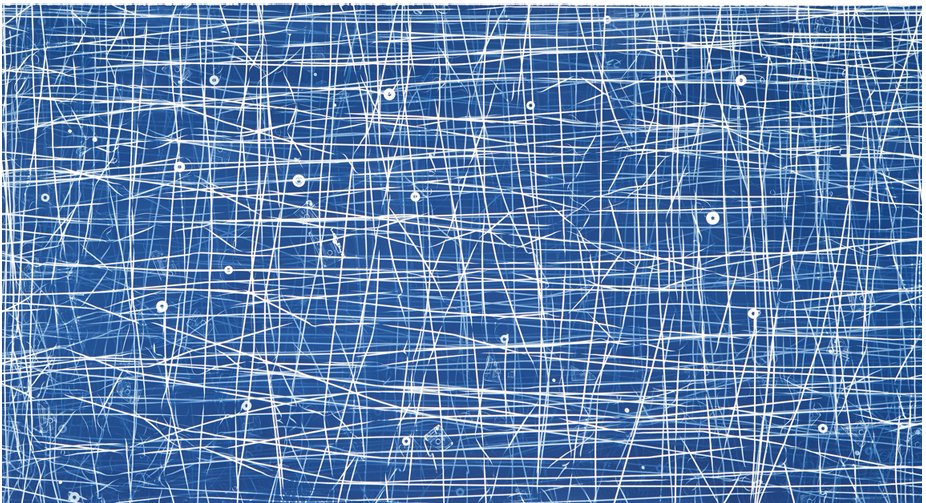

The latter isn’t just a figure of speech. The ballistic-grade Plexiglass cubes on plinths that snake down the center of Ratio 3’s main room, collectively titled Modern Ensembles, each contain the multicolored residue of an explosion set off within. Oppenheimer worked with a pyro-technician (a former employee of the Disney Corporation, no less) to create custom-made charges of various explosive chemicals that were then detonated inside the cubes, resulting in gorgeous, nebula-like washes of color that completely cover each cube’s interior face.

That the beauty of the Modern Ensembles comes from such violent origins is less interesting to me (that’s an old story in Art History, particularly in regards to action painting, a tradition which these sculptures extend as much as they do classic Minimalism’ proverbial cube), than how they embody a tension between explosive force and containment. The Oakland occupiers also hit a wall — a phalanx of police armed with riot gear and tear gas. It’s hard not to think of that moment, that so many experienced remotely via Facebook posts and Flickr feeds, when viewing these chemically colored cubes that, although transparent, you can’t actually see through.

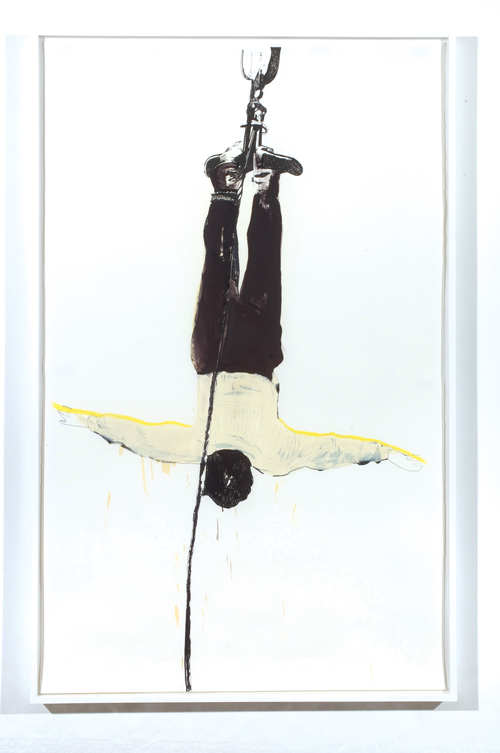

Communication breakdown is also taken up in Social Failure and Black Signs, a suite of five pigment prints that surround the enigmatic vitrines like a gaggle of lost protestors. Each black and white image consists of a similarly-positioned arm holding aloft a sign printed with phrases concerning governance or economics but clearly removed, media res, from their original context. “Tolerated, as unfortunate excess,” reads one. Another states, “everything, but it is not enough.”

These stranded phrases are, in fact, excerpts from interviews with political figures such as Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, Fidel Castro and Robert McNamara, in which they discuss moments when their ideologies resulted in policy failure, something which Oppenheimer’s photographs formally restage by transforming these confessional moments into incomplete sound bytes.

The opposite tack is used to achieve similarly disorienting results in Anthems, a four minute high definition video, which superimposes footage of a military marching band playing four different national anthems while in formation. The resulting wall of sound renders the pieces indistinguishable from each other, while, visually, the rapidly overlaid footage scrambles the patterned order of military spectacle.

Politically, a lot can happen when polyphony gives way to cacophony (or in the case of Social Failure and Black Signs when signal becomes noise). But the result can also just be chaos. As an ongoing experiment in the messy business of building a participatory democracy with its share of successful and failed words and deeds, the Occupy movement is a living, ever-expanding testament to this. And despite being presented under a title full of Freudian dramatics, so are the pieces in Inside Us.

GEOF OPPENHEIMER: INSIDE US ALL THERE IS A PART THAT WOULD LIKE TO BURN DOWN OUR OWN HOUSE

Through December 10

Ratio 3

1447 Stevenson, SF.

(415) 821-3371