1. Cosmopolis (David Cronenberg, Canada/France/Portugal/Italy) During the five times I watched this brilliantly slow-burning, transcendental flick, I saw dozens of audience members fall asleep, walk out early, and complain all the way down the corridor of the Embarcadero Center Cinema hallways. I had to watch it that many times (plus read the book and have countless late-night discussions) just to try and wrap my brain around this era-defining exploration of what it means to be a (hu)man in the Y2Ks. Robert Pattinson proved he’s a truly spectacular actor, Paul Giamatti has never been better, and David Cronenberg is only getting better as he gets older.

2. In the Family (Patrick Wang, US, 2011) Self-distributed due to its length (169 minutes), this is a stunningly haunting and devastating work. Viewers with the patience to stick with it are rewarded with a genuinely achieved emotional volcano that I can only relate to John Cassavetes’ greatest films. A truly landmark film, in both style and content.

3. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, US) Of all the films that Anderson has boldly attempted, audaciously experimented with, and (perhaps most importantly) been critically embraced for, The Master is a balanced period piece that combines both poetic and historical elements with a couple of truly profound performances by Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman. This is not a film only about Scientology, or about just one master. This is a film that asks many questions, but supplies few answers.

4. The Comedy (Rick Alverson, US) Perhaps containing the most mean-spirited characters of the decade, this harrowingly insightful satire of the hipster generation’s compulsion to heap irony upon irony inspired many an audience member to exit mid-film. But the many who dared to remain (including fans of the film’s lead actor, Tim Heidecker, from Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!) may have found themselves forced to question their own heartless (and even sociopath) tendencies.

Director Rick Alverson’s perceptive use of a contemporary antihero is quite comparable to the counterculture characters of the 1970s: Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver (1976), Peter Falk in Husbands (1970), and Jack Nicholson in Five Easy Pieces (1970). And since The Comedy was not necessarily made to be enjoyed, it will probably, sadly, take 20 years for people to recognize that there is no finer film to define this generation.

5. Florentina Hubaldo CTE (Lav Diaz, Philippines) With this six-hour film, Lav Diaz has created yet another minimalist masterpiece that few will even attempt to watch — 20 people started out in the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts’ screening, and only 10 finished it. Diaz has a monumental goal in mind for his character, and his film’s length is a major part of achieving it. I am not sure if there will ever be a time when six-hour character studies will be all the rage, but until then, Diaz is paving an uncharted road for others to follow.

6. Shanghai (Dibakar Banerjee, India) This Hindi remake of Costa-Gavras’ monumental political thriller Z (1969) may not have French New Wave cinematographer Raoul Coutard behind the camera, but Shanghai‘s director of photography Nikos Andritsakis adds his own brand of raw intensity. For his part, writer-director Banerjee creates an even more complicated look at the state of politics in the age of the modern terrorist. Seemingly inspired by fellow director Ram Gopal Varma’s career of gritty political dramas, Banerjee is an international director to watch.

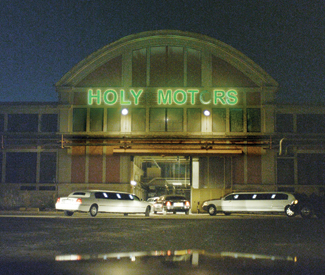

7. Holy Motors (Leos Carax, France) The perfect companion to David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis, this film contains a tour de force performance by the almighty Denis Lavant (of Claire Denis’ 1999 Beau Travail), with Michel Piccoli, Eva Mendes, Édith Scob, and Kylie Minogue in supporting roles. Unique, surreal, and completely inspired, this day-in-the-life journey will make you want to watch it again as soon as it ends.

8. The Grey (Joe Carnahan, US) The best existential “animal attacking human” flick since David Mamet’s 1997 cult classic The Edge. It’s a film that showcases Liam Neeson as he tapes glass to his fists to battle a pack of giant wolves — and manages to be emotionally stirring at the same time. Make sure to keep watching all the way through the credits.

9a. Your Sister’s Sister (Lynn Shelton, US, 2011) Lynn Shelton’s follow-up to her genre-defining bromance Humpday (2009) is a pitch-perfect indie that attempts to dig deep within its dark and confused characters. Depressed and confused thirtysomething Jack (played by Mark Duplass, master of casual awkwardness) heads off to a remote island to figure out his life. The only trouble: his best friend (a mesmerizing Emily Blunt) also has a lesbian sister (Rosemarie DeWitt) who is already there doing her own soul searching. With this contemplative, honest, and hilarious film, Shelton is turning out to be quite a splendid voice for our current generation of progressive pitfallers.

9b. Jeff, Who Lives At Home (Jay Duplass and Mark Dupass, US) They’ve done it again! With Jeff, the mumblecore masters (2005’s The Puffy Chair; 2010’s Cyrus) construct a stoner comedy-existential trip for the man-child generation. While inspiring outstanding performances from Jason Segal and Ed Helms (both the best they’ve ever been), playing brothers, a poignantly performance by Susan Sarandon as their mother raises this wonderfully earned sentimental indie flick to the ranks of family dramas like Jodie Foster’s Home for the Holidays (1995) and her most recent overlooked gem, The Beaver (2011).

10. Lotus Community Workshop (Harmony Korine, US) His next film, Spring Breakers (due out next year), is poised to become Harmony Korine’s most accessible film to date; it’s a T&A-filled exploitation film, led by James Franco as a grimy, gold-grilled-grinning, dreadlocked drug dealer who lives to prey on bikini-clad young girls. But 30-minute meta-masterpiece Lotus Community Workshop, which played the San Francisco International Film Festival earlier this year (as part of omnibus film The Fourth Dimension), is maybe Korine’s greatest film to date. The almighty Val Kilmer plays a dirt bike-riding, fanny-pack wearing, roller-rink guru named Val Kilmer — and yep, it’s as mind-blowing as it sounds.

11. ParaNorman (Chris Butler and Sam Fell, US) This stop-motion animated film surprised parents who felt its PG rating should have been PG-13 — and it inspired gasps and even yells (from adults!) in every screening I attended. Daringly shot on a Canon 5D Mark II DSLR Camera and released in a fully utilized 3D, this ode to midnight movies is a kids’ film that will stand the test of time and should rank right alongside Shaun of the Dead (2004) and Army of Darkness (1992): horror parodies that transcended their own self-awareness and become classics themselves.

12-14 [tie]. A Simple Life (Ann Hui, Hong Kong, 2011), Amour (Michael Haneke, Austria/France/Germany), The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky, Hungary/France/Germany/Switzerland/US, 2011) Ann Hui’s simple, straightforward tale of a woman’s choice to check herself into a retirement home after suffering a stroke will probably get overshadowed by Michael Haneke’s wonderfully minimalist approach to an elderly couple’s decline after one of them experiences the same ailment. Meanwhile, Béla Tarr’s final film is for acquired tastes only; it’s a cyclical journey with a rural couple, who eat potatoes, are isolated in a stormy darkness, and care for their horse. All three films lay out a terrifyingly realistic blueprint of old age.

15. Compliance (Craig Zobel, US) No film at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival encountered as much controversy as Compliance. At the first public screening, an all-out shouting match erupted, with one audience member yelling “Sundance can do better!” You can’t buy that kind of publicity. Every screening that followed was jam-packed with people hoping to experience the most shocking film at the fest. And it doesn’t disappoint: Zobel unleashes an uncomfortable psychological mindfuck on the viewer all the way through to the stunning final 15 minutes, which are even more shocking than all the twists and turns that came before.

16. The Kid With a Bike (Jean-Pierre Dardenne and Luc Dardenne, Belgium/France/Italy, 2011) Can these Belgian brothers make a bad film? Seriously? Like their Palme D’Or winners Rosetta (1999), The Son (2002), and L’enfant (2005), Kid is yet another hypnotic, neo-realist portrait of modern-day youth. Every character makes unexpected yet inevitable decisions. No moment is false. The Dardennes create movies that make life feel more real.

17. Beasts of the Southern Wild ( Benh Zeitlin, US) Fantastical special effects created by 31 students at San Francisco’s own Academy of Art University (yes, I am biased), plus star Quvenzhané Wallis as Hushpuppy, a precocious six-year-old searching to understand a world post-Katrina, post-race, and more importantly post-childhood. Combining David Gordon Green’s George Washington (2001), Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are (2008) and perhaps even Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991), Zeitlin has created a haunting enigma for modern audiences that deserves multiple viewings. But even though it won multiple prizes at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, will it get the Oscar attention it deserves?

18. Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning (John Hyams, US) When Jean-Claude Van Damme started this franchise back in 1992, it was a nice little combo of First Blood (1982), The Terminator (1984) and Robocop (1987). Twenty years later, the series’ fourth entry is co-written, co-edited, and directed by John Hyams, the son of Peter Hyams, who directed JCVD classics Timecop (1994) and Sudden Death (1995) — and man oh man does he deliver a tough and gritty little action sci-fi film. Van Damme takes on an even darker role than his scene-stealing turn in Expendables 2; with a cleverly subversive script, eloquently choreographed fight scenes (one of which gives Dolph Lundgren some pretty priceless moments), and a denouement that has to be seen to be believed, you may be rooting for this VOD released genre film as much as I am — not to mention Indiewire, which called it “One of the Best Action Movies of the Year!”

19. John Carter (Andrew Stanton, US) With a budget of $250 million, this epic based on Edgar Rice Burroughs stories brought the Walt Disney company to its knees by only making $73 million back. If you saw the film in 3D, you might be confused as to why no one bothered to see it. In my opinion (having watched it twice), John Carter achieves everything James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) did, as far as sci-fi extravaganzas go, but it also has an inspired story and a charming cast: Taylor Kitsch, Lynn Collins, Samantha Morton, and Willem Dafoe. This is possibly this generation’s Ishtar (1987), and like Elaine May’s infamous still-unavailable bomb, John Carter is actually enjoyable; it’ll need a decade or two for audiences to find it as one of the most enjoyable CGI spectacles in recent years.

20. The Dark Knight Rises (Christopher Nolan, US) [SPOILER ALERT!] I found The Dark Knight Rises hard to dismiss as just another money-making super-hero adaptation. After multiple viewings, I’ve come to think of the conclusion to the trilogy as the finest of the three. I’ve also had time to puzzle over the film’s intricate plot.

While many fellow critics seemed to find the film’s political handlings of Bane’s Occupy/French Revolution movement to be flimsy and even irresponsible, I would argue that the film works in a more complicated way toward politics. If Bane’s misguided revolution fell flat, then it would be important to look at Catwoman’s anarchist ways. And about that — did she put her selfishness aside to start over with a broke Bruce Wayne, or is the closing sequence just Alfred’s fantasy? (And if the latter is true, did Batman actually blow himself up in the end?)

And then there’s Blake, who bests the pathetic Deputy Commissioner, then turns his back on the well-meaning yet lying-to-the-people Commissioner Gordon. Though Blake knows he has to quit the police force amid such corruption, he can’t dismiss his urge to help the helpless and downtrodden — after all, he’s an orphan from the streets — and Robin is born. He’s alone (no butlers down in that cave anymore …), and will need to figure out what to do in Gotham City — a town that’s always wild at heart and weird on top.

(Note: list compiled prior to viewing Zero Dark Thirty or Les Misérables.)

Best Actor of 2012

Matthew McConaughey for Bernie (Richard Linklater, US, 2011), Killer Joe (William Friedkin, US, 2011), Magic Mike (Steven Soderbergh, US, 2011), and The Paperboy (Lee Daniels, US)

Best Unreleased Films of 2012

The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn, and Anonymous, Denmark/Norway/UK)

Black Rock (Katie Aselton, USA)

Berberian Sound Studio (Peter Strickland, UK)

Pilgrim Song (Martha Stephens, US)

The Lords of Salem (Rob Zombie, US)

Jesse Hawthorne Ficks programs the Midnites for Maniacs series, which emphasizes dismissed, underrated, and overlooked films. He is the Film History Coordinator at Academy of Art University.