arts@sfbg.com

DANCE While watching Garrett + Moulton Productions’ exhilarating The Luminous Edge, the dramaturgical concept of “a well-made piece” kept popping up in my mind. At a time when “process-oriented” and “in progress” work seem to be the currency of the day, seeing structurally rigorous dance, in which ingredients are impeccably integrated into something akin to a universe of its own, seemed almost antediluvian. The accomplishment is all the more impressive, given the fact that until a few years ago, co-choreographers (and real-life couple) Janice Garrett and Charles Moulton kept their professional careers strictly apart. I can’t think of any other partnership like this one.

With no rough edges or tentative moments, each of Luminous’ elements — music, dance, design — contributed to the work’s confident trajectory. After 70 minutes, it curled in on itself, and instead of its final moments feeling predictable, they felt right. We emerge from a void, and we return to it, Garrett and Moulton appeared to tell us.

There is no narrative, but individually distinct episodes suggest a story, perhaps embodied by three ever-so-different couples: company dancers Carolina Czechowska and Michael Galloway, Tegan Schwab and Dudley Flores, and Vivian Aragon and Nol Simonse. Throughout they engaged with each other and in solos that built on their special abilities. Except for one small duet between Flores and Simonse, as couples they stayed put.

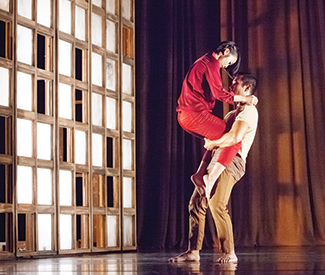

Luminous looked at the joys and pains of being alive — the intimacy and struggles of relationships, but also a profound sense of being at the mercy of forces beyond our understanding. The sheer brilliance of the interweaving between the black-clad movement choir and the dancers — the women in Mary Domenico’s crimson skirts with just a trace of a misplaced train, the men in simple dark blue — set into the relief how the personal exists within something larger.

As originally developed some 30 years ago, Moulton’s “movement choir” choreography (small, precise gestures in overlapping unison, performed sitting in tiers) always looked vaguely threatening. The discipline involved had something militaristic about it. Those elements are still there, but the choir has become an infinitely more expressive instrument, on par with the soloists. It envelops, protects, and constrains, but it also welcomes and opens vistas. Fingers can be claws, but filigreed they promise a gentler way of being.

In Luminous’ opening, the choir formed a fluid honor guard through which the three couples traveled, as if entering a new world. When the larger group reshaped itself into circles around them, I thought of the many cultures in which round dances are integral to wedding rituals — except here, their speed seemed more ominous than welcoming.

Later on, in one of the work’s more chilling moments, the soloists stood in brilliant separate spotlights (the first-rate lighting design throughout was by David Robertson). Staring impassively at us, disembodied hands caressed, measured, and examined their bodies. The dancers looked like pieces of meat for sale. In another section, the choir bunched into a tight group of fist-shaking arms as one of the dancers disappeared among them, swallowed up by a mob.

But these dark moments were balanced by those in which folkloric exuberance broke through as if from an almost forgotten memory. The company dancers spoke most powerfully about triumphs and tragedies of life. In their roles they celebrated, they struggled, and they also buried each other.

Almost shyly partnered by Galloway, Czechowska could appear impassive and self-absorbed until her long limbs fiercely tore into and claimed the space around her. Aragon is a firecracker of athletic exuberance, but when crumpled over Simonse’s leg, she became a different person. Schwab’s grounded physicality looked particularly open to being partnered on equal footing with the liquidly dancing Flores. Again and again, they reached for each other’s hands in a tug of war that never seemed to end.

Luminous wouldn’t exist without the extraordinary contribution of composer-musical director Jonathan Russell, his six musicians, and guest singer Karen Clark, all performing live upstage left. The choreographers had first intended to work with Mahler’s unbearably anguished Kindertotenlieder. I am glad they didn’t. Instead, Russell chose rich selections from his own and Marc Mellits’ music. They set the tone for each of Luminous’ parts. Brilliantly, however, he also chose three songs from Mahler’s masterful score and arranged them for Clark’s rich voice.

But Russell and the two choreographers gave an 11th century woman, Hildegard von Bingen, first say:

O strength of Wisdom

who, circling, circled,

enclosing all

in one lifegiving path,

three wings you have:

one soars to the heights,

one distils its essence upon the earth,

and the third is everywhere.

Praise to you, as is fitting,

O Wisdom. *