STREET FIGHT San Francisco’s politics of mobility devolved into a cesspit this summer. Beginning with Mayor Ed Lee’s retreat on Sunday parking meters, purportedly to garner support for his transportation bond and vehicle license fee proposals, Lee’s bait and switch ultimately backfired.

Rather than nudge the city’s transit finance debate in a sensible, progressive direction, confusion and duplicity by the mayor and some supervisors over parking policy has instead empowered a Tea Party-like faction that’s placed a backwards initiative on the November ballot.

This Restore Transportation Balance Initiative (Proposition L) is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. It’s got nothing to do with balance, but would instead seek to substitute a “cars-first” policy for the city’s longstanding “transit-first” paradigm. Although only an advisory measure, its main effect would be to provide the mayor and supervisors more cover to do nothing except shrug and kick the can of sustainable transportation policy down the road.

This is exactly what the car-firsters want, just as Republicans in Congress have thwarted President Obama’s agenda for mitigating climate change. These local drivers hope to stall efforts to make San Francisco more pedestrian-friendly, block Muni improvements, and make sure bicycles don’t slow them down or get in the way of unfettered, gluttonous free parking for private cars on public streets.

In that vein, the Restore Balance crowd has lifted a script from the infamous Koch brothers, securing finances from a Facebook billionaire (Sean Parker funded the measure’s signature-gathering effort) and speaking about transportation policy in a manner reminiscent of climate change deniers. Any bike lane, parking management effort, or Muni improvement is, in their eyes, out of balance with a city that should be betrothed solely to cars.

Meanwhile, as Muni fares went up this summer without any objection from mayor “nickel-and-dime,” a ballot measure put forth by Sup. Scott Wiener joins the crowded field as Proposition B. His proposal would devote more General Fund monies to Muni operations, but it’s unclear what impact this might have on other important city programs like housing or social services.

It’s a good thing City Hall went on summer recess, because we’ll all need some time to sift through all this muck.

TOWARDS CAR-FREE VACATIONS

Speaking of vacations, let’s talk about the good, bad, and ugly of car-free vacationing using Amtrak and a bicycle. I recently took Amtrak’s Coast Starlight north from Oakland to Portland, with my touring bicycle in tow. In Portland, I surveyed some of the bicycle and transit infrastructure before a 950-mile bike tour back to San Francisco along the Oregon and California coasts.

The Coast Starlight is a relaxing way to travel up to Portland. It has comfortable and roomy seating with outlets for plugging in phones or other devices, and the views of Mt. Hood and Oregon’s verdant forests and valleys are breathtaking. Most importantly, taking the train from Oakland to Portland produces far fewer carbon emissions than flying or driving the same distance.

A flight to Portland produces 14 times the carbon emissions compared to the train. Driving up I-5 in a new car with decent fuel economy produces 26 times the emissions of the train. This is an incredible difference that must be factored into national transportation policies, and it does not include the full life cycle assessment of each mode, such as petroleum extraction, manufacturing vehicles, waste disposal, infrastructure (concrete is a huge CO2 emitter), and so on. While carpooling might reduce per capita driving emissions, traveling with friends or family on Amtrak reduces them even further.

But Amtrak has some bad aspects. The coffee needs immediate mitigation! It’s an easy problem to solve, and I’ve had delicious coffee on German and Swiss trains, even in ceramic mugs.

Getting a bicycle on many Amtrak trains is annoying. Unlike the Capitol Corridor or San Joaquin trains, on which you can simply roll the bicycle on board, Amtrak’s long-distance trains require boxing the bicycle as checked baggage. This means additional charges, and you must arrive and disembark at a station that handles baggage, so many stops are not bicycle-accessible. And the cardboard bike box is not reused by Amtrak but put in recycling, which is rather silly and wasteful.

Fortunately, Amtrak is starting to get it, and soon will be introducing bicycle roll-on service on many trains on the East Coast. Let’s hope Amtrak does the same for the Coast Starlight. There’s plenty of room on the multilevel rail cars to squeeze in a few bikes, and that would probably attract more people to use the system while making it more flexible.

Now for the ugly. The trip to Portland takes more than 17 hours on a good day. I’m not necessarily arguing for high-speed rail, but this length of time is a big problem for Amtrak. It’s not a technology problem — it’s politics.

Amtrak is caged by the timetable of freight railways that own the tracks. This often results in delays since the freight railroads have eliminated double tracks and rationalized their routes to maximize profit while having little concern about passenger rail.

Over 100 years ago, Edward Harriman, who merged Southern Pacific with Union Pacific into a continent-wide system, had it right on running a railroad. Instead of focusing on shareholder wealth, Harriman argued that profits from railroads should be shoveled back into reducing grades, strengthening bridges, improving curves, double-tracking trunk routes, and building new bridges, cutoffs, sidings, tunnels, stations, yards, cars, and terminals. Harriman even proposed a rail tunnel under San Francisco Bay, which as I’ve written about before and which should be a priority in the region today.

Rail is critical infrastructure and key to our national energy and climate policy. It should not be left to the whims of freight haulers and private profit. It’s time for the political will to coordinate the right-of-way to improve travel times as well as increase frequency of passenger trains.

Six years ago, improving Amtrak was a signature platform of the Obama Administration. But Republicans — many filled with racist vitriol — have fought anything he stands for. And they hate Amtrak almost as much as they hate Obama.

During the 2012 presidential campaign, Republicans vowed to gut Amtrak and mocked Obama’s pro-Amtrak policies. In Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin, the hate ran so deep that funding for rail was simply sent back to Washington, even as cities in all of those states pined for rail as an economic development strategy. This kind of zombie-like Republican hate towards Obama and Amtrak is remarkably similar to the posturing of the anti-transit, car-firsters pushing Prop L.

THE PORTLAND COMPARISON

But I’m on vacation, and problems of Amtrak’s ugly politics aside, once in Portland it all got beautiful. Cycling around Portland is fantastic. With excellent, well-connected bicycle facilities coupled with attentive and polite drivers, bicycle-oriented innovation and businesses flourish in Portland. I’ve never seen so many cargo bikes and families with children out shopping, cycling to school, and making other utilitarian trips by bicycle.

Sure, it’s flatter, but more important is the traffic density and allocation of street space. Compared to San Francisco, Portland has lower residential density, a low density of automobiles, and more capacity to reallocate road space for bicycling.

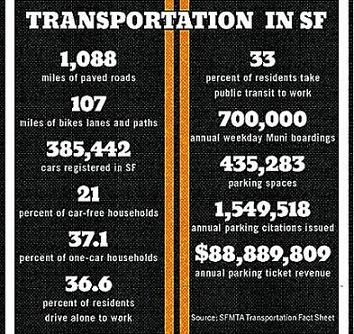

To get to Portland-style cycling, we need to recognize that San Francisco’s 9,000-plus cars per square mile is extreme and out of control, and San Francisco politicians need to embrace much tighter parking management and street management policies.

I should also add that Portland does have its own ugly right-wing backlash against bikes and transit. For example, in suburban Clackamas County, dubbed “Clakistan” by some, Tea Party-types voted to stall light rail expansion. But in the city, the bicycle and rail transit are embraced with enthusiasm.

Oregon is also refreshingly welcoming to bicycle tourists. For those leaving Portland by bicycle, state and local transportation departments have produced wonderful maps with route suggestions, and the official state highway map includes a bicycle map showing highway shoulder widths and identifies state parks with bike-friendly camping, hot showers, and other services. One state park bike campground even had a solar-powered charging station so cyclists can check their phones.

Unlike California parks, which also have affordable and accessible bicycle camping sections, Oregon places sites away from the noisy RV and automobile campsites, providing peace and tranquility and level ground for tents.

Since cycle tourists don’t always know their timing or exact route, Oregon and California do not require reservations, which enables flexibility for bike touring. And the sites are cheaper — usually $5 in both states, but some California campgrounds charge $7 — because bicyclists have a much lighter impact on parks compared to cars and RVs.

SHARE THE ROAD

All of this made bicycle touring from Portland to San Francisco inspiring, energizing, invigorating, revitalizing, and really just a whole lot of fun. Waking up early to pedal through the Cape Lookout area of Oregon or the Avenue of the Giants in California was truly amazing.

But the big downside was high-speed traffic whizzing by at certain points along the coast (but not all). So the same methods used to make city streets safe for cycling could apply everywhere, including for bicycle touring. Rural traffic is faster than city traffic, so we really need to separate cyclists from speeding traffic if substantial numbers of people (including families) are to take on bike touring.

Rail trails and fully separated cycle ways in parts of Oregon (Banks Vernonia) and California (near Arcata and also Samuel P. Taylor Park) should be expanded and made part of a coastal bikeway using the rights-of-way along Highway 101 and 1.

Where full separation is not possible, wider shoulders cleared of the nasty detritus of car glass or metal should be provided. Shoulders should be regularly cleaned and crumbling edges patched. At tight spots, such as on Highway 1 between Fort Ross and Jenner, narrow portions of roadway could be made into signal-controlled one-way segments such as what is done in construction zones.

Reducing the speed limits and using traffic calming should also be promoted on the coast highways. This is a tourist route, not Interstate 5, so even the Subaru-driving weekend warriors and RVs can slow it down. Rural areas in California and Oregon can benefit greatly with more bicycle tourism (as well as auto tourists slowing down).

We cyclists don’t drag a ton of Costco provisions up to the campgrounds. We shop and eat locally, at each increment, and spend hard cash in small towns. Slowing the cars and RVs down would draw them into the local stores and restaurants as well. And every few days, we cycle tourists get a motel or bed-and-breakfast room.

I saw and spoke with several families with children touring the Oregon coast, with no motorized vehicle support. In Oregon and parts of California, buses also accommodate bicycles, so getting to the coast is easier than you’d think, even if greater frequency would be helpful.

As I pedaled the Avenue of the Giants, I saw an old Northwestern Pacific railway bridge over the Eel River. It would be so civilized if the Sonoma-Marin (SMART) rail line were extended north to Eureka and Arcata, with a spur to Fort Bragg, enabling one to access (and bicycle tour) the Redwoods and California coast from the Bay Area without a car.

Pedaling through Marin and towards the Golden Gate Bridge last Sunday was also truly inspiring. There were hundreds of cyclists out on the regular Marin circuit, many with friendly waves and greetings. The Golden Gate Bridge was packed with smiling cyclists out for a rigorous Mt. Tam ride or rental bikes heading to Sausalito.

If you share in the dream of car-free vacations and bicycle touring, I urge you look at the California Bicycle Coalition’s upcoming organized bike tour from Santa Barbara to San Diego. This could be your launching point for rethinking how we vacation in America.

Street Fight is a monthly column by Jason Henderson, a geography professor at San Francisco State University and the author of Street Fight: The Politics of Mobility in San Francisco.