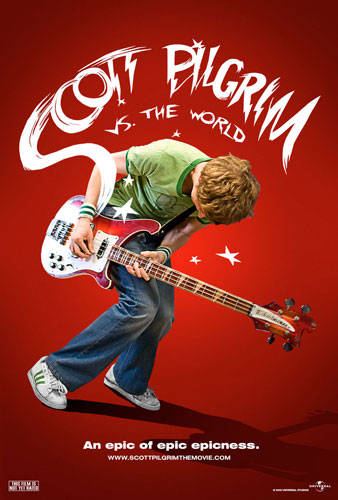

Go here to read Sam Stander’s review of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World in this week’s Guardian. What follows is Stander’s complete interview with director Edgar Wright.

San Francisco Bay Guardian: What is your favorite visual effect or sight gag in all of Scott Pilgrim?

Edgar Wright: Oh my god. There’s so much … I probably have to pick, off the top of my head, I like watching the twins scene because it was only very recently finished, so I’d have to pick that.

SFBG: How did you originally get involved in adapting Scott Pilgrim?

EW: I was given the book six years ago, when the first volume came out, by … the producers who had kind of leapt on the rights to it before it was even in bookstores. And I really loved the book, and I thought it would be a really interesting thing to try and adapt. At that point there was only the one book. [We] began a five-year process of working on it as [author Bryan Lee O’Malley] continued to develop the books, so the development of the film and the books kind of went in tandem in places. So it’s kind of been, six years ago I was given the book, and now the final book just was released, and the film is coming out, too.

SFBG: How many books were there when the film was in production? Were there four?

EW: By the time we started filming, there were five and the sixth book had been kind of half-written. But over the course of the production, I’m thinking of various stages where we stalled for time as much as we could, so that we could get as much material as possible. But there was a decision made early on that the two things would have to be different beasts, and Bryan was certainly aware of that, and understood that that would be the case. In a way, I think he actually preferred there being two different versions, that the film could be an alternate-reality version of the comic.

SFBG: But you still definitely kept a lot of the details of the comic. I was curious what inspired the choice to visually represent sound effects.

EW: I kind of figured that, you know, it’s a huge part of comics that most people completely jettison, because usually comic book adaptations are striving for reality. I thought, as well, it made sense within Scott Pilgrim that the character would choose to live his life like that, that Scott Pilgrim, as a character who’s grown up on a diet of Saturday morning cartoons and gaming, would actually choose to live his life that way if he could, and have points pop up and sound effects pop out when the doorbell rings. Because the books are funny and imaginative, it was just a way of embracing that kind of imagination within the artwork. It wasn’t a film where we had to strive for absolute realism like The Dark Knight. We had a chance to embrace the bubblegum, pop art nature of the artwork.

SFBG: It reminded me in places of the opening titles to ’60s Batman, which I enjoyed.

EW: Oh, I was always a fan of that show as a kid. I like some of those ’60s comic book adaptations that would embrace the form of the comics a little more. I guess, you know, in the ’80s, with the Tim Burton Batman, comic book movies started to strive for legitimacy, but we didn’t really have to do that with this. It was something where we could actually have fun with the form.

SFBG: I was wondering if the characters of Shaun from Shaun of the Dead or Tim from Spaced — how you see them in relation to Scott as a protagonist, or even Ramona?

EW: I think Scott Pilgrim has some things in common with Shaun and Tim Bisley. Tim Bisley and Shaun are both older than Scott Pilgrim, and I think maybe, you know, Tim is in his mid-20s, so he’s a bit more frustrated than Scott Pilgrim is. I think Scott Pilgrim is still in that sort of stage in his life where he’s powered by blind optimism, and I don’t think he’s necessarily a character who’s been worn down by the harsh realities of life yet, and that kind of effects everything he does, in terms of — the way that he pursues Ramona is like the way you pursue a shiny object in a videogame. I don’t think he’s really had his hard knocks yet, and this film is slightly about him getting his karmic comeuppance. I think Shaun is Scott Pilgrim plus about ten years, where he’s kind of settled into a slightly more lazy, depressed state. He’s kind of given up, slightly.

SFBG: I was curious, who came first: Gideon or Jason Schwartzman?

EW: Gideon came first. There was a drawing of Gideon back in 2004. I remember when I first read the first book, there was the first book and the script for the second book, but then there were also sketches of all the other exes and their stats that Bryan had drawn. So he’d drawn all of them way back in 2004. But the Gideon sketch back in 2004 looks uncannily like Jason and what he eventually drew for the sixth book.

SFBG: In light of having just made a movie entirely referencing videogames, what do you have to say to Roger Ebert’s constant claim that videogames aren’t a form of art?

EW: I think that the film shows both the good and the bad, in a way, in terms of, there’s elements of Scott Pilgrim’s character as maybe a slightly thoughtless person in the way that he powers through life and doesn’t necessarily think about the feelings of the people around him, and even treating them sometimes like bit players on his quest, that that shows maybe a downside to being lost in the world of gaming, and he’s forced to face the consequences later in the film. But then, I think sometimes the criticism about videogames stems from games that are pretty generic, because there is art and brilliant design and amazing ideas at work in gaming and game design, and I think that that would be difficult to deny, in a sense, that there are artists as good as the people working at Pixar working in games today.

But I think that some of the negative articles that are written about games are usually referring to games that are more generic and just concentrate on violence and destruction, that are kind of Xeroxes of films. So I think sometimes there are probably some games that undo the good work done by others, maybe. I’m sure that’s part of it. And then you get videogame adaptations … that are Xeroxes of a Xerox. I can see where that criticism comes from, I don’t necessarily agree with it, because I feel like … on a design level, Nintendo has become sort of the Walt Disney for our era, in a way. I mean, the characters are so identifiable and so beloved. And you get some games that are just works of beauty and interaction, so I can see it go both ways, you know. I would hope Roger Ebert would enjoy this film on the basis that we namechecked Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, so I would hope we could score brownie points even if he didn’t like the videogame stuff in it.

SFBG: With the development of the characters, certainly a lot of the comedy of the characters in the comics comes from playing with various stereotypes — of the way people behave in relationships, also jokes about Knives’ Chinese heritage and Wallace being gay, and different characters coming from different contexts like that. I was curious what level of depth do you perceive these characters having, as opposed to being sort of absurd caricatures?

EW: Well, I think a lot of those people came from friends and colleagues of Bryan Lee O’Malley, because Toronto is a very multicultural society, and Bryan himself is half Irish and half Japanese. The two characters you just mentioned, I know Knives and Wallace are based on real people. In the books at least, and certainly in the film, it’s an attempt to show actually a very ethnic community. We tried, in terms of the gay characters in the film to kind of, in hopefully a progressive way, not make a big deal about it. I’m actually quite proud that we have a PG-13 rating when sometimes that has been, you know — depicting homosexual relationships is sometimes frowned upon by the MPAA, or given a more restrictive rating. So it’s actually nice in a studio comedy to have characters who are gay and out, and there’s no stigma about it whatsoever.

SFBG: Definitely, in the United States, Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz are really seen as archetypally very English comedies. Were you trying to work as a Canadian comedy director with Scott Pilgrim, or how do you see it relating to that?

EW: I don’t know, I’ve always found that question difficult to answer because I don’t really know how my sense of humor or what I find funny particularly relates to Britain, because I grew up on comedy from all around the world. Obviously, I really like a lot of British comedy, but a lot of my favorite comedy films are American. I wouldn’t like to thing that my sense of humor is completely defined by where I’m from. So I didn’t try and put a Canadian hat on to direct Scott Pilgrim. I tried to just be myself.

SFBG: I was curious about the music in the movie. I thought it was really interesting that you got some of the bands that it seemed like Bryan Lee O’Malley was sort of lampooning in the comic to do the actual music, and I was wondering what the process was for picking those bands and getting them involved.

EW: Basically, we had an embarrassment of riches in terms of the people that came on to collaborate. I know that Bryan had drawn Envy Adams based on a live shot of Metric in performance … but I think that most of the bands are a mélange of bands that he played with when he was in a band himself. I think some of the bands in Scott Pilgrim are kind of lampooning his own efforts, and other bands that were doing that circuit at the time. But, you know, in terms of the artists coming on board, everybody was really excited to be a part of it. And I think in the case of the bands, they got to also play a part, they’re sort of almost cast as characters in the film. I mean, Broken Social Scene’s songs in the film don’t sound anything like Broken Social Scene, and Beck was channeling his earlier, fuzzier roots. So I think people had fun playing a part rather than playing themselves. Even the Metric track that’s in the film is them almost doing a pastiche of themselves. In that case, with the track “Black Sheep,” [Metric frontwoman] Emily Haines had said it was a track they left off the last album because they thought it maybe sounded like somebody doing an impression of Metric. And so when I heard that, I said, ‘Well, that’s the song that we want!’”

SFBG: You also worked on the screenplay for the upcoming Tintin film, right?

EW: I did. Not for very long, sadly, because I got busy on Scott Pilgrim, but I worked on a couple of drafts, and it was very exciting to work on.

SFBG: Was that adaptation-of-a-comic experience similar to Scott Pilgrim or notably different?

EW: Well, different in the sense that [Tintin creator] Hergé is dead, so you don’t get a chance to — in that case, radically different, because you’re only going on his work and his life, rather than actually being able to talk to the creator himself. Unlike with Scott Pilgrim, I couldn’t call Hergé every day, so I could only go on reading those books and trying to recapture how I felt about them when I was eight when I read them.

SFBG: All right, anything else you want to say about the film?

EW: Go and see it in theaters.

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World opens Fri/13 in Bay Area theaters.