news@sfbg.com

The day City College of San Francisco heard it would close was the same day, July 3, that 19-year-old Dennis Garcia signed up for his fall classes.

With a manila folder tucked under his arm, he turned the corner away from the registration counter and strode by a wall festooned with black and white sketches of every City College chancellor since 1935, including a portrait of bespectacled founder Archibald Cloud. In a meeting room on the other side of that wall, the college’s current administrators were receiving the verdict from the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges.

It was their worst fears of the past year realized: City College’s accreditation was being revoked. Accreditation is necessary for the college to receive state funding, for students to get federal loans, and for the degree to be worth more than the paper it’s printed on.

Unbeknownst to Garcia, he walked out of the building just as the college received its death sentence, which is scheduled to be carried out next July unless appeals now underway offer a reprieve. In the interim, CCSF will essentially be a ward of the state, stripped of the local control it has enjoyed since Cloud’s days.

Just a few blocks down Ocean Avenue is the nerve center of City College’s teachers union. Housed in a flat above a Laundromat, the scent of freshly washed clothes wafted up the staircase to an office that instantly became a flurry of ringing phones and rushed voices.

Only an hour later, 10 or so union volunteers were calling their members, contacting nearly 1,600 City College faculty whose responses ranged from sad to furious. The volunteers read them bulleted factoids about accreditation and a call to join an upcoming protest march.

But the woes of City College reach deeper than a three line script could ever cover, and can be traced back to the oval office itself, leading to a really odd question: Did President Obama kill City College?

PRESSURE FROM THE TOP

When the president trumpeted education in his 2012 State of the Union speech, he sounded an understandable sentiment. “States also need to do their part, by making higher education a higher priority in their budgets,” Obama told the nation. “And colleges and universities have to do their part by working to keep costs down.”

But the specifics of how to cut costs were outlined by years of policymaking and a State of the Union supplement sheet given to the press.

The president’s statement said that they will determine which colleges receive aid, “either by incorporating measures of value and affordability into the existing accreditation system; or by establishing a new, alternative system of accreditation that would provide pathways for higher education models and colleges to receive federal student aid based on performance and results.”

The emphasis is ours, but the translation is very simple: College accreditation agencies can either enforce the administration’s numbers-based plan or be replaced. The president’s college reform is widely known and hotly debated in education circles. Commonly known as the “completion agenda,” with an emphasis on measurable outcomes in job placement, it had its start under President George W. Bush, but Obama carried the torch.

The idea is that colleges divest from community-based programs not directly related to job creation or university degrees, and use a data measurement approach to ensure two-year schools transfer and graduate students in greater numbers. “Community colleges” would quickly become “junior colleges,” accelerating a slow transition that began many years ago.

But its critics say completion numbers are screwy: They discount students who are at affordable community colleges just to learn a single skill and students who switch schools, administrator Sanford Shugart of Valencia College in Florida wrote in an essay titled “Moving the Needle on College Completion Thoughtfully.”

Funding decisions made from completion numbers affect millions of students nationwide — and CCSF has now become the biggest laboratory rat in this experiment in finding new ways to feed the modern economy.

“I think there was a general consensus that the country is in a position that, coming out of the recession, we have diminished resources,” Paul Feist, spokesperson for the California Community College Chancellor’s Office, told us. “Completion is important to the nation — if you talk to economic forecasters, there’s a huge demand for educated workers. Completion is not a bad thing.”

Like dominoes, the federal agenda and Obama’s controversial Secretary of Education Arne Duncan tipped the Department of Education, followed by the ACCJC, and now City College — an activist school in an activist city and an institution that openly defied the new austerity regime.

WINNING THE BATTLE

In the ACCJC’s Summer 2006 newsletter, Brice Harris — then an accreditation commissioner, now chancellor of the state community college system — described the conflict that arose when colleges rallied against completion measurements established by the federal government.

“In the current climate of increased accountability, our regional accrediting associations find that tight spot to be more like a vice,” Harris wrote.

Many of the 14 demands the ACCJC made of City College trace back to the early days of Obama’s administration, when local trustees resisted slashing the curriculum during the Great Recession.

“There’s a logic to saying ‘We don’t want to put students on the street in the middle of a recession,'” said Karen Saginor, former City College academic senate president. “If you throw out the students, you can’t put them in the closet for two years and bring them back when you have the money.”

And they have a lot of students — more than 85,000. Like all community colleges in California, the price of entry is cheap, at $46 a unit and all welcome to attend. But since 2008, the system was hammered with budget cuts of more than $809 million, or 12 percent of its budget.

So programs were cut, including those for seniors, ex-inmates re-entering society, or young people enrolling to learn Photoshop or some other skill without committing to a four-year degree.

“As the recession hit, the Legislature instructed the community college system [to] prioritize basic skills, career technical, and transfer,” Feist said. “That’s to a large extent what we did. That was the reshaping of the mission of that whole system.”

It’s easy to cast the completion agenda as a shadowy villain in a grand dilemma, but as Feist or anyone on the federal level would note, people were already being pushed out of the system, to the tune of more than 500,000 students since the 2008-09 academic year due to the budget crisis. Course offerings have been slashed by 24 percent, according to the state chancellor’s office.

But City College would only go so far. Then-Chancellor Don Q. Griffin raised the battle cry against austerity and the completion agenda at an October 2011 board meeting, his baritone voice sounding one of his fullest furies.

“It was obvious to me when I heard Bush … and then Obama talking about the value of community colleges … they’re going to push out poor people, people of color, people who cannot afford to go anywhere else except the community college,” he said.

But when it came to paying for that pushback, things got tricky.

“No more of this bullshit, that we turn the other way and say it’s fine. We’re going to concentrate the money on the students,” Griffin said at a December 2011 board meeting. “You guys are talking about cutting classes, we don’t believe in that. Cut the other stuff first, cut it until it hurts, and then talk about cutting classes.”

So he slashed his own salary and lost staff through attrition and other means. The college had more than 70 administrators before 2008, and it now has fewer than 40.

“Since the recession in 2009, we’ve been seen as the rebels,” said Jeffrey Fang, a former student trustee on City College’s board. “When most of the colleges went and made cuts in light of the recession, we decided to find ways to keep everything open while doing what we could to eliminate spending.”

But those successes in saving classes put City College on a collision course with its accreditor.

LOSING THE WAR

Seven years ago, the ACCJC found six deficiencies that it asked City College to fix, finding it had too many campuses serving too many students, fiscal troubles, and hadn’t enforced measurement standards. Last year, it faulted City College for resisting those changes and tacked on eight additional demands, threatening to revoke its accreditation.

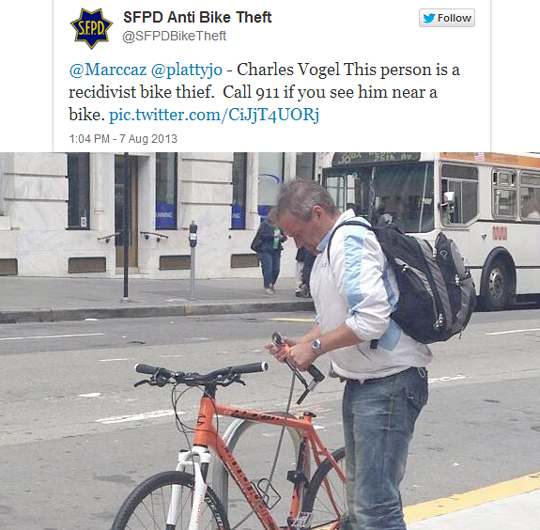

Speaking on condition of anonymity, an official who worked closely with ACCJC as a member of one of the visiting accreditation teams told us there was pressure to crack down on all the Western colleges.

“The message they’re hearing from (ACCJC President) Barbara Beno is that Washington is demanding, ‘Why are you not being more strict with institutions with deficiencies that have lasted more than two years [and taking action] to revoke their accreditation?'” the source said.

This official said this may soon ripple to other accreditation agencies. “What’s anomalous about California is we’re getting to where everyone will be in a few years.”

The ACCJC’s next evaluation is this December, where it will be reviewed by the Department of Education. It wants to be ready, says Paul Fain, a reporter for Inside Higher Ed, a national trade publication.

“Washington writ large … is pushing very hard on accreditors to drive a harder line,” Fain told us. “There’s a criticism out there that accreditation is weak and toothless.”

The U.S. Department of Education declined to comment on the issue, saying only that it will formally respond to all officially filed complaints about ACCJC.

But the numbers speak volumes. As an ACCJC newsletter first described federal pressure back in 2006, seven community colleges in California were on probation or warning by the ACCJC. By 2012 that number leapt to 28.

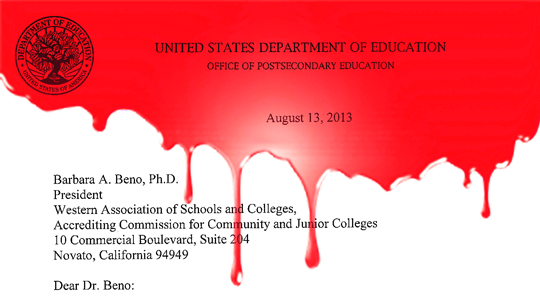

But the California Federation of Teachers is fighting back, and recently filed a 280-page complaint about the ACCJC with the Department of Education.

The allegations were many: Business conflict of interest from a commission member, failure to adhere to its own policies and bylaws, and even the commission President Beno’s husband having served on City College’s visiting team, which the unions said is a clear conflict of interest.

Some people think it’s a waste of time, that City College has already lost.

“That process of fighting accreditation won’t succeed, it just forestalls the problem,” said Bill McGinnis, a trustee on Butte College’s board for over 20 years. He’s also served on many ACCJC visiting teams.

But the unions are making some headway. The Department of Education wrote a letter to the ACCJC telling them to respond in full to the complaints by July 8, as this article goes to press. The accreditor will soon be the one evaluated.

WHAT’S NEXT?

In the meantime, City College has exactly one year to reverse its fortunes: The loss of accreditation doesn’t actually kick in until July, 2014. A special trustee appointed by the state will be granted all the powers of the locally elected City College Board of Trustees to get with the federal program. Without voting power, the elected body is effectively castrated.

No one knows what that will mean for the college board, not even Mayor Ed Lee, who issued a statement supporting the state takeover and criticizing local trustees for not cutting enough. “The ACCJC is fundamentally hostile to elected boards and they’ve made that clear,” City College Trustee Rafael Mandelman told us. “The Board of Trustees should and may look at all possible legal options around this.”

Although officials say classes will proceed as normal for the next year, some aren’t waiting around to see if City College will survive.

At its last board meeting, the CCSF Board of Trustees grappled with how to address dwindling enrollment. As news of its accreditation troubles spread, City College has been under-enrolled by thousands of students, exacerbating its problems. Since the state funds colleges based on numbers of students, City College’s funding is plummeting by the millions.

A frightening statistic: When Compton College lost its accreditation in 2005 and was subsequently absorbed by a neighboring district, it lost half its student population, according to state records.

Even the faculty is having a hard time hanging on, said Alisa Messer, the college’s faculty union president.

“People are looking for jobs elsewhere already. Despite everyone’s dedication to see the college through, it has tried everyone and stretched them to the limit,” she told us.

The college has two hopes — that the CFT wins its lawsuit and can reverse the ACCJC decision, or that the new special trustee can somehow turn the college around by next July. But either way, something will be lost. “City College is definitely changing,” Saginor said. “What it will change into, and if those changes will be permanent, that I don’t know.”