arts@sfbg.com

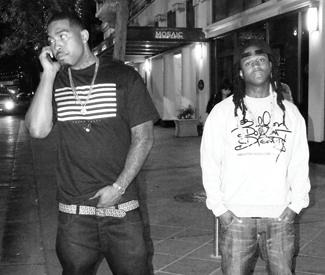

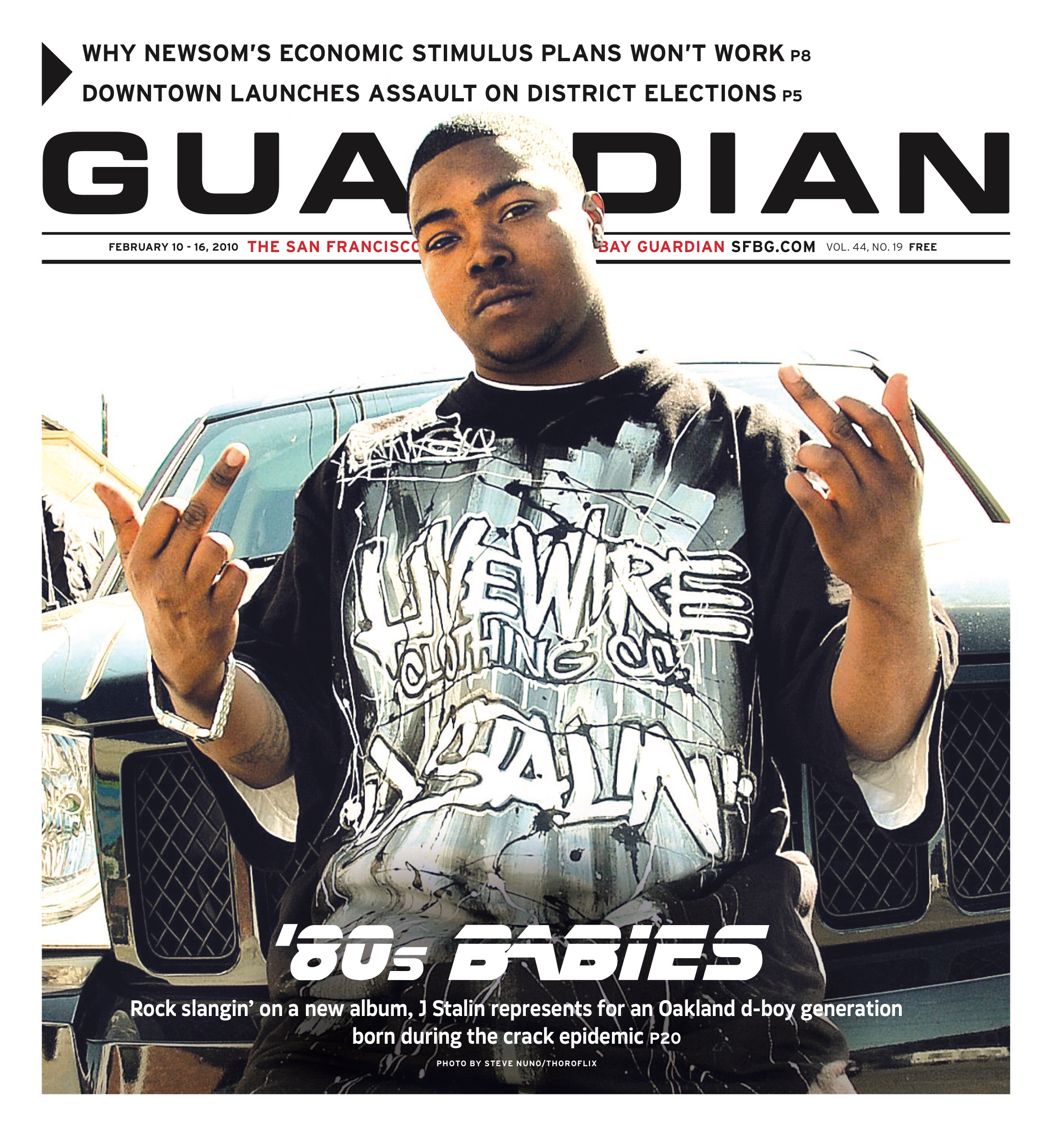

I remember the day I met J.Stalin, 10 years ago. He bounced into the Mekanix’s East Oakland studio, walked up to me, and shook my hand.

“I’m J.Stalin. I write and record two songs a day,” he said proudly. Rail-thin, barely 5 feet tall, he looked like a middle-schooler. While he’s thickened somewhat in adulthood, the pint-size rapper retains an air of adolescence that’s one of the keys to his enduring success. Kids in the hood love Stalin because he seems like them and his music speaks to them. He looks like what he once was, a d-boy on the corner slanging rocks. Yet his music is versatile, with a profound undercurrent of melancholy to his storytelling and a huge streak of ’80s R&B in his sound, both of which appeal to adults. Even without radio support, this potent combination has made him one of the most popular rappers not simply in Oakland but in the Bay Area, period, and when I hear a car roll up playing a local artist, more often than not these days, that artist is J.Stalin.

“Make sure you put that in,” Stalin says. “I’m the most played person on the streets in cars.”

It reminds me of our first meeting — but only a little, for, despite his youthful appearance, it’s hard to discern the eager youngster of a decade ago in the somber adult he’s become in his late 20s.

We’re sitting poolside in a middle-of-nowhere suburb where J’s tucked himself away with his girlfriend and 2-month-old son. I couldn’t imagine living out here, but it’s the perfect retreat for a rapper, away from the distractions of the hood. Coming from the cramped public housing of West Oakland’s Cypress Village, Stalin can appreciate the surrounding blandness in ways I can’t. And, of course, he’s on the road frequently, fresh from a sold-out West Coast tour with Husalah and Roach Gigz and about to embark on a series of appearances for his new album, S.I.D. (Shining In Darkness) (Livewire/Fontana), which will take him as far afield as Ohio.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ETUKFgYaEw

Named for his cousin, Sidney Malone, who died in 2008 at age 25 after suffering cardiac arrest during pacemaker surgery, S.I.D. showcases a different side of Stalin’s music than previous releases, even as it leans heavily on production from his longtime producers, the Mekanix, in addition to tracks by Mob Figaz maestro Roblo and HBK member P-Lo.

“With this record, I wanted to get back to making fun music,” he says. “When you come from the streets, and done been through hella shit, sometimes that’s all you want to talk about. It ain’t even like you rappin’. You just expressing your emotions. I love making street music, but my own music be depressing to me sometimes. I’m always going to give you that classic Stalin, but that’s the difference between this album and the last album: I wanted more uptempo tracks you can dance to.”

“I didn’t want to just name it, ‘In Memory of Sid,’ so I came up with Shining In Darkness, because that’s where the Bay at,” he continues. “We shining over here but the industry don’t put a spotlight on it. It’s just a darkness to the rest of the country. The more I started recording on it the more the meaning unfolded to me. Like when you hear it, you’re like, ‘Why don’t the world know about this nigga?’ But at the same time I just wanted to keep Sid’s memory alive; that was my biggest fan.”

In another departure, S.I.D. is Stalin’s first disc since July of last year, when he released his DJ Fresh-produced double-disc Miracle & Nightmare on 10th Street (Livewire/World’s Freshest), his first project to crack the Billboard rap charts, at #60.

“It’ll be like nine months since I dropped a project,” he says. “I’ve been focusing on putting out dope albums instead of flooding the music with quick mixtapes and shit.”

It’s a sign of how much rap has changed since the analog era, when E-40’s innovation as an independent artist was to drop an album “like a pregnant beeyatch, every 8 or 9 months,” compared with the lethargic, every year or two pace of major-label acts. Raised in the generation of the laptop studio, Stalin was among the innovators delivering a constant stream of music to his fans in the form of mixtapes, collaborations, and side projects in between proper solo albums. Waiting nine months between projects is almost unheard of for J, who has something like 30 discs to his credit at this point.

“I’ve been trying to work more strategically,” he says. “Work smarter, not harder. I’ve been doing more of the clothing line, selling Livewire Clothing at all my shows. Been doing a lot of pop-up stores in stores selling them, plus we got the online store. I popped off my website; I be giving away free music on there. My new artists Lil June and L’Jay, you can download they albums on my website.”

This is another key to Stalin’s success: He’s always thought of himself not simply as an artist, but as the CEO of Livewire Records, a company he has conjured into existence through sheer force of will, his own talent, and an uncanny ability to form alliances and develop artists. Even the short list of Livewire artists — Shady Nate, Philthy Rich, Stevie Joe, Lil Blood — is impressive, and Stalin is constantly building the roster. He still talks to major labels from time to time, but the decline of their business model, coupled with his success going through Universal’s independent distribution channel, Fontana, there’s not much the majors can offer him these days.

“Really, if ain’t nobody trying to give me money to put out multiple artists and projects, there’s not really no point. We at the position now where all the things that the label is talking about, we damn near can do ourselves,” he concludes. “Unless they giving out some millions — not one million, millions.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7e78hZlPwks