tredmond@sfbg.com

The intersection of Cesar Chavez and Evans Avenue is a good enough place to start. Face south.

Behind you is Potrero Hill, once a working-class neighborhood (and still home to a public housing project) where homes now sell for way more than a million dollars and rents are out of control. In front, down the hill, is one of the last remaining industrial areas in San Francisco.

Go straight along Evans and you find printing plants, an auto-wrecking yard, and light manufacturing, including a shop that makes flagpoles. Take a right instead on Toland, past the Bonanza restaurant, and you wander through auto-glass repair, lumber yards, plumbing suppliers, warehouses, the city’s produce market — places that the city Planning Department refers to at Production, Distribution, and Repair facilities. Places that still offer blue-collar employment. There aren’t many left anywhere in San Francisco, and it’s amazing that this district has survived.

Cruise around for a while and you’ll see a neighborhood with high home-ownership rates — and high levels of foreclosures. Bayview Hunters Point is home to much of the city’s dwindling African American population, a growing number of Asians, and much higher unemployment rates than the rest of the city.

Now pull up the website of the Association of Bay Area Governments, a well-funded regional planning agency that is working on a state-mandated blueprint for future growth. There’s a map on the site that identifies “priority development area” — in planning lingo, PDAs — places that ABAG, and many believers in so-called smart growth, see as the center of a much-more dense San Francisco, filled with nearly 100,000 more homes and 190,000 new jobs.

Guess what? You’re right in the middle of it.

The southeastern part of the city — along with many of the eastern neighborhoods — is ground zero for massive, radical changes. And it’s not just Bayview Hunters Point; in fact, there’s a great swath of the city, from Chinatown/North Beach to Candlestick Park, where regional planners say there’s space for new apartments and condos, new offices, new communities.

It’s a bold vision, laid out in an airy document called the Plan Bay Area — and it’s about to clash with the facts on the ground. Namely, that there are already people living and working in the path of the new development.

And there’s a high risk that many of them will be displaced; collateral damage in the latest transformation of San Francisco.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND “SMART GROWTH”

The threat of global climate change hasn’t convinced the governor or the state Legislature to raise gas taxes, impose an oil-severance tax, or redirect money from highways to transit. But it’s driven Sacramento to mandate that regional planners find ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in California cities.

The bill that lays this out, SB375, mandates that ABAG, and its equivalents in the Los Angeles Basin, the Central Coast, the Central Valley and other areas, set up “Sustainable Communities Strategies” — land-use plans for now through 2040 intended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 15 percent.

The main path to that goal: Make sure that most of the 1.1 million people projected to live in the Bay Area by 2040 be housed in already developed areas, near transit and jobs, to avoid the suburban sprawl that leads to long commutes and vast amounts of car exhaust.

The notion of smart growth — also referred to as urban infill — has been around for years, embraced by a certain type of environmentalist, particularly those concerned with protecting open space. But now, it has the force of law.

And while ABAG is not a secret government with black helicopters that can force cities to do its will — land-use planning is still under local jurisdiction in this state — the agency is partnering with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, which controls hundreds of millions of dollars in state and federal transportation money. And together, they can offer strong incentives for cities to get in line.

Over in Contra Costa and Marin counties, at hearings on the plan, Tea Party types (yes, they appear to exist in Marin) railed against the notion of elite bureaucrats forcing the wealthy enclaves of single-family homes to accept more density (and, gasp, possibly some affordable housing). In San Francisco, it’s the progressives, the transit activists, and the affordable housing people who are starting to get worried. Because there’s been almost zero media attention to the plan, and what it prescribes for San Francisco is alarming — and strangely nonsensical.

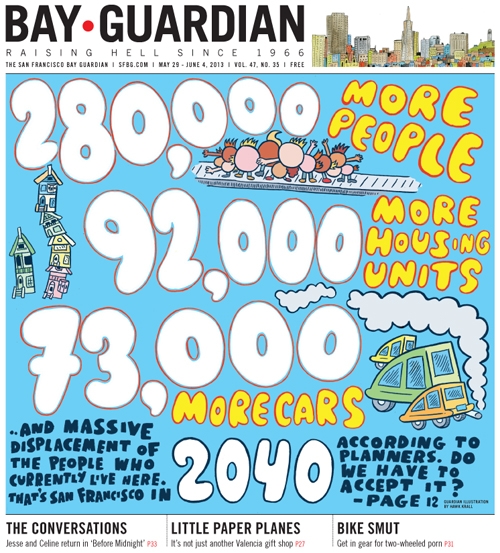

Under the ABAG plan, San Francisco would approve 92,400 more housing units for 280,000 more people. The city would host 190,000 more jobs, many of them in what’s called the “knowledge economy,” which mostly means high tech. Second and third on the list: Health and education, and tourism.

The city currently allows around eight cars for every 10 housing units; as few as five in a few neighborhoods, at least 10 in many others. And there’s nothing in any city or regional plan right now that seeks to change that level of car dependency. In fact, the regional planners think that single-occupancy car travel will be the mode of choice for 48 percent of all trips by 2040 — almost the same as it is today.

And since most of the new housing will be aimed at wealthier people, who are more likely to own cars and avoid catching buses, San Francisco could be looking for ways to fit 73,000 more cars onto streets that are already, in many cases, maxed out. There will be, quite literally, no place to park. And congestion in the region, the planners agree, will get a whole lot worse.

That seems to undermine the main intent of the plan: Transit-oriented development only works if you discourage cars. In a sense, the car-use projections are an admission of failure, undermining the intent of the entire project.

The vast majority of the housing that will be built will be too expensive for much of the existing (and even future) workforce and will do little to relieve the pressure on lower income people. But there is nothing whatsoever in the plan to ensure that there’s money available to build housing that meets the needs of most San Franciscans.

Instead, the planners acknowledge that 36 percent of existing low-income people will be at risk for displacement. That would be a profound change in the demographics of San Francisco.

Of course, adding all those people and jobs will put immense pressure on city services, from Muni to police, fire, and schools — not to mention the sewer system, which already floods and dumps untreated waste into the Bay when there’s heavy rain. Everyone involved acknowledged those costs, which could run into the billions of dollars. There is nothing anywhere in any of the planning documents addressing the question of who will pay for it.

THE NUMBERS GAME

Projecting the future of a region isn’t easy. Job and population growth isn’t a straight line, at best — and when you’re looking at a 25-year window in a boom-and-bust area with everything from earthquakes to sea-level rise factoring in, it’s easy to say that anyone who claims to know what’s going to happen in 2040 is guessing.

But as economist Stephen Levy, who did the regional projections for ABAG, pointed out to us, “You have to be able to plan.” And you can’t plan if you don’t at least think about what you’re planning for.

Levy runs the Center for the Continuing Study of the California Economy, and he’s been watching trends in this state for years. He agrees that some of his science is, by nature, dismal: “Nobody projects deep recessions,” much less natural disasters. But overall, he told me, it’s possible to get a grip on what planners need to prepare for as they write the next chapter of the Bay Area’s future.

And what they have to plan for is a lot more people.

Levy said he started with the federal government’s projections for population growth in the United States, which include births and deaths, immigration, and out-migration, using historic trends to allocate some of that growth to the Bay Area. There’s what appears at first to be circular logic involved: The feds (and most economists) project that job growth nationally will be driven by population — that is, the more people live in the US, the more jobs there will be.

Population growth in a specific region, on the other hand, is driven by jobs — that is, the more jobs you have in the Bay Area, the more people will move here.

“Jobs in the US depend on how many people are in the labor force,” he said. “Jobs in the Bay Area depend on our share of US jobs and population depends on relative job growth.”

Make sense? No matter — over the years it’s generally worked. And once you project the number of people and jobs expected in the Bay Area, you can start looking at how much housing it’s going to take to keep them all under a roof.

Levy projects that the Bay Area’s share of jobs will be higher than most of the rest of the country. “This is the home of the knowledge industry,” he told me. So he’s concluded that population in the Bay Area will grow from 7.1 million to 9.2 million — an additional 2.14 million people. They’ll be chasing some 1.1 million new jobs, and will need 660,000 new housing units.

Levy stopped there, and left it to the planners at ABAG to allocate that growth to individual cities — and that’s where smart growth comes in.

For decades in the Bay Area, particularly in San Francisco, activists have waged wars against developers, trying to slow down the growth of office buildings, and later, luxury housing units. At the same time, environmentalists argued that spreading the growth around creates serious problems, including sprawl and the destruction of farmland and open space.

Smart growth is supposed to be an alternative: the idea is to direct new growth to already-established urban areas, not by bulldozing over communities (as redevelopment agencies once did) but by the use of “infill” — directing development to areas where there’s usable space, or by building up and not out.

ABAG “focused housing and jobs growth around transit areas, particularly within locally identified Priority Development Areas,” the draft environmental impact report on the plan notes.

The draft EIR is more than 1,300 pages long, and it looks at the ABAG plan and several alternatives. One alternative, proposed by business groups, would lead to more development and higher population gains. Another, proposed by community activist groups including Public Advocates, Urban Habitat, and TransForm, is aimed at reducing displacement and creating affordable housing; that one, it turns out, is the “environmentally preferred alternative.” (See sidebar).

But no matter which alternative you look at, two things leap out: There is nothing effective that ABAG has put forward to prevent large-scale displacement of vulnerable communities. And despite directing growth to transit corridors, the DEIR still envisions a disaster of traffic congestion, parking problems, and car-driven environmental wreckage.

THE DISPLACEMENT PROBLEM

ABAG has gone to some lengths to identify what it calls “communities of concern.” Those are areas, like Bayview Hunters Point, Chinatown, and the Mission, where existing low-income residents and small businesses face potential displacement. In San Francisco, those communities are, to a great extent, the same geographic areas that have been identified as PDAs.

And, the DEIR, notes, some degree of displacement is a significant impact that cannot be mitigated. In other words, the gentrification of San Francisco is just part of the plan.

In fact, the study notes, 36 percent of the communities of concern in high-growth areas will face displacement pressure because of the cost of housing. And that’s region wide; the number in San Francisco will almost certainly be much, much higher.

Miriam Chion, ABAG’s planning and research director, told me that displacement “is the core issue in this whole process.” The agency, she said, is working with other stakeholders to try to address the concern that new development will drive out longtime residents. But she also agreed that there are limited tools available to local government.

The DEIR notes that ABAG and the MTC will seek to “bolster the plan’s investment in the Transit Oriented Affordable Housing Fund and will seek to do a study of displacement. It also states: “In addition, this displacement risk could be mitigated in cities such as San Francisco with rent control and other tenant protections in place.”

There isn’t a tenant activist in this town who can read that sentence with a straight face.

The problem, as affordable housing advocate Peter Cohen puts it, is that “the state has mandated all this growth, but has taken away the tools we could use to mitigate it.”

That’s exactly what’s happened in the past few decades. The state Legislature has outlawed the only effective anti-displacement laws local governments can enact — rent controls on vacant apartments, commercial rent control, and eviction protections that prevent landlords from taking rental units off the market to sell as condos. Oh, and the governor has also shut down redevelopment agencies, which were the only reliable source of affordable housing money in many cities.

Chion told me that the ABAG planners were discussing a list of anti-displacement options, and that changes in state legislation could be on that list. Given the power of the real-estate lobby in the state Capitol, ABAG will have to do more than suggest; there’s no way this plan can work without changing state law.

Otherwise, eastern San Francisco is going to be devastated — particularly since the vast majority of all housing that gets built in the city, and that’s likely to get built in the city, is too expensive for almost anyone in the communities of concern.

“This plan doesn’t require affordable housing,” Cindy Wu, vice-chair of the San Francisco Planning Commission, told me. “It’s left to the private market, which doesn’t build affordable housing or middle-class housing.”

In fact, while there’s plenty of discussion in the plan about where money can come from for transit projects, there’s virtually no discussion of the billions and billions that will be needed to produce the level of affordable housing that everyone agrees will be needed.

Does anyone seriously think that developers can cram 90,000 new units — at least 85 percent of them, under current rules, high-cost apartments and condos that are well beyond the range of most current San Franciscans — into eastern neighborhoods without a real-estate boom that will displace thousands of existing residents?

Let’s remember: Building more housing, even a lot more housing, won’t necessarily bring down prices. The report makes clear that the job growth, and population boom that accompanies it, will fuel plenty of demand for all those new units.

Steve Woo, senior planner with the Chinatown Community Development Center, sees the problem. In a letter to ABAG, he notes: “Plan Bay Area and its DEIR has analyzed the displacement of low-income people and explicitly acknowledges that it will occur. This is unacceptable for San Francisco and for Chinatown, where the pressures of displacement have been a constant over the past 20 years.”

Adds the Council of Community Housing Organizations: “It would be irresponsible for the regional agencies to advance a plan that purports to ‘improve’ the region’s communities as population grows while the plan simultaneously presents great risk and uncertainty for many vulnerable communities.”

Jobs are at stake, too — not tech jobs or office jobs, which ABAG projects will expand, but the kind of industrial jobs that currently exist in the priority development areas.

Calvin Welch, who has been watching urban planning and displacement issues in San Francisco for more than 40 years, puts it bluntly: “It is axiomatic that market-rate housing drives out blue-collar jobs,” he said.

Of course, there’s another potential problem: Nobody really knows where jobs will come from in the next 25 years, whether tech will continue to be the driver or whether the city’s headed for a second dot-com bust. San Francisco doesn’t have a good record of building for projected jobs: In the mid-1980s, for example, the entire South of Market area (then home to printing, light manufacturing, and other blue-collar jobs) was rezoned for open-floor office space because city officials projected a huge need for “back-office” functions like customer service.

“Where are all those jobs today?” Welch asked. “They’re in India.”

TOO MANY CARS

For a plan that’s designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by moving residential development closer to work areas, Plan Bay Area is awfully pessimistic about transportation.

According to the projections, there will be more cars on the roads in 2040, with more — and much worse — traffic. The DEIR predicts that a full 48 percent of all trips in 2040 will be made by single-occupant vehicles — just slightly down from current rates. The percentage of trips on transit will only be a little bit higher — and there’s no significant increase in projected bicycle trips.

That alone is pretty crazy, since the number of people commuting to work by bike in San Francisco has risen dramatically in the past 10 years, and the city’s official goal is that 20 percent of all vehicle trips will be by bike in the next decade.

Part of the problem is structural. Not everyone in San Francisco 2040 is going to be a high-paid tech worker. In fact, the most stable areas of employment are health services and government — and hospital workers and Muni drivers can’t possibly afford the housing that’s being built. So those people will — the DEIR acknowledges — be displaced from San Francisco and forced to live elsewhere in the region (if that’s even possible). Which means, of course, they’ll be commuting further to work. Meanwhile, if current trends continue, many of the people moving into the city will work in Silicon Valley.

Chion and Levy both told me that the transit mode projections were based on historical trends for car use, and that it’s really hard to get people to give up their cars. Even higher gas prices and abominable traffic delays won’t drive people off the roads, they said.

If that’s the case — if auto culture, which is a top source of global climate change, doesn’t shift at all — it would seem that all this planning is pointless: the seas will rise dramatically, and San Franciscans ought to be buying boats.

“The projections don’t take into account social change,” Jason Henderson, a geography professor at San Francisco State University and a local transportation expert, told me. “And social change does happen.”

Brad Paul, a longtime housing activist who now works for ABAG, said these projections are just a start, and that the plan will be updated every four years. “I think we’re finding that the number of people who want to drive cars will go down,” he said.

Henderson argues that the land-use policy is flawed. He suggests that it would make more sense to increase density in the Bay Area suburbs along the BART lines. “Elegant development in those areas would work better,” he said. You don’t need expensive high-rises: “Four and five stories is the sweet spot,” he explained.

Most of the transportation projects in the plan are already in the pipeline; there’s no suggestion of any major new public transit programs. There is, however, a suggestion that San Francisco adopt a congestion management fee for downtown driving — something that city officials say is the only way to avoid utter gridlock in the future.

SIDELINING CEQA

ABAG and the MTC have a fair amount of leverage to implement their plans. MTC controls hundreds of millions of dollars in transit money; ABAG will be handing out millions in grants to communities that adopt its plan. And under state law, cities that allow development in PDAs near transit corridors can gain an exemption from the California Environmental Quality Act.

CEQA is a powerful tool to slow or halt development, and developers (and some public officials) drool at the prospect of getting a fast-track pass to avoid some of the more cumbersome parts of the environmental review process.

Under SB 375 and Plan Bay Area, CEQA exemptions are available to projects that meet the Sustainable Community Strategy standards and are close to transit corridors. And when you look at the map of those areas, it’s pretty striking: All of San Francisco, pretty much every square inch, qualifies.

That means that almost any project almost anywhere in town can make a case that it doesn’t need to accept full CEQA review.

The most profound missing element in this entire discussion is the cost of all this growth.

You can’t cram 210,000 more residents into San Francisco without new schools, parks, and child-care centers. You can’t protect those residents without more police officers and firefighters. You can’t take care of their water and sewer needs without substantial infrastructure upgrades. And even if there’s state and federal money available for new buses and trains, you can’t operate those systems without paying drivers, mechanics, and support workers.

There’s no question that the new development will bring in more tax money. But the type of infrastructure improvements that will be needed to add 25 percent more residents to the city are really expensive — and every study that’s ever been done in San Francisco shows that the tax benefits of new development don’t cover the costs of public services it requires.

When World War II and the post-war boom in the Bay Area brought huge growth to the region, property taxes and federal and state money were adequate to build things like BART, the freeways, and hundreds of new schools, and to staff the public services that the emerging communities needed. But that all changed in 1978, with the passage of Prop. 13, and two years later, with the election of Ronald Reagan as president.

Now, federal money for cities is down to a trickle. Local government has an almost impossible time raising taxes. And instead of hiking fees for new residential and commercial projects, many communities (including San Francisco) are offering tax breaks to encourage job growth.

Put all that in the mix and you have a recipe for overcrowded buses, inadequate schools, overstressed open space (imagine 10,000 new Mission residents heading for Dolores Park on a nice day), and a very unattractive urban experience.

That flies directly in the face of what Plan Bay Area is supposed to be about. If the goal is to cut down on commutes by bringing new residents into developed urban areas, those cities have to be decent places to live. What would it cost to accommodate this level of new development? Five billion dollars? Ten billion? Nobody knows — because nobody has run those numbers. But they’re going to be big.

Because just as tax dollars have been vanishing, the costs of infrastructure keep going up. It costs a billion dollars a mile to build BART track. It’s costing more than a billion to build a short subway to Chinatown. Just upgrading the sewer system to handle current demands is a $4 billion project.

And if the developers and property owners who stand to make vast sums of money off all of this growth aren’t going to pay, who’s left?

The ABAG planners point out, correctly, that there’s a price for doing nothing. If there’s no regional plan, no proposal for smart growth, the population will still increase, and displacement will still happen — but the greenhouse gas emissions will be even worse, the development more haphazard.

But if the region is going to spend all this money and all this time on a plan to make the Bay Area more sustainable, more livable, and more affordable in 25 years, we might as well push all the limits and get it right.

Instead of looking at displacement as inevitable, and traffic as a price of growth, the planners could tell the state Legislature and the governor that it’s not possible to comply with SB375 — not until somebody identifies the big sums of money, multiples of billions of dollars, needed to build affordable housing; not until there are transit options, taxes, and restrictions on driving.

Because continued car use and massive displacement — the package that’s now facing us — just isn’t an acceptable option.