tredmond@sfbg.com

Every gang member on the streets knows Cathey and Sands. They’re the cops. They’ve busted dozens of the young men who hang out in the Mission. They know every excuse, every trick, every way you can duck into an alley, hide in a doorway, ditch a weapon or cover up a crime.

But today, as they cruise around 24th Street in an unmarked car, Officers John Cathey and David Sands are not talking about putting bad guys in prison. They’ve been there, done that — and a year or two ago, they got so sick of seeing teenagers ruining their lives that the two tough cops decided to take another approach.

The officers pull their unmarked car into a side street, where two young men are walking together. They’re Norteños, Cathey explains, part of the gang that controls the southern part of the neighborhood, and they’ve got the telltale red colors all over them. Red shirts, red caps, red strips on their shoes.

Cathey approaches the young men and asks them what they’re doing. “Nothing,” they say.

They look at him as if they know what’s coming next, and chances are they do. It happens all the time these days in the world of the Mission District gangs. Cathey is about to give “The Speech.” The one that hundreds of gangbangers have heard, over and over. The one that’s already saved a few of their lives.

“You know what happened last night?” he asks. The kids feign ignorance. “Sure you do,” he continues. “A bunch of your guys got arrested. Your buddy just turned 18 and he got caught. He’s going to big-boy jail.”

The kids in red look at the ground.

“You want to wind up like that, you keep doing what you’re doing,” Cathey says. “You want to do something different, we can get you a job. A decent job, pays real money, in six months you get benefits. You know you don’t have to do this. You know we can help.”

For a second, one young man looks interested. “You come by the station, you leave your number for me, we’ll be in touch,” Cathey says. Then the moment’s over, the Nortenos walk away, and the two cops get back in the car.

“We might have a chance with him,” Cathey tells me. “I’m like water, I wear them down.”

********

Latino gangs — primarily two violent rival operations that run drugs and kill each other — have been a serious problem in the Mission for years. Kids as young as 11 or 12 are getting recruited into a life that typically leads to Juvenile Hall, state prison, or death. The city, and nonprofits that work with youth, have run all sorts of gang-prevention programs, with some success and a lot of failure.

While the Mission rapidly becomes a cool place for rich high-tech workers to live, the violence continues. In the past seven months, 10 people, most of them under 25, have been shot in gang-related incidents; three are dead.

But there’s a new, somewhat radical approach going on now — and it comes largely from two police officers who get paid to arrest gang members and instead are devoting their lives to keeping them out of jail.

Cathey and Sands, 11-year veterans, friends from their days in the Police Academy, have, pretty much on their own initiative, created a grassroots program that allows young men and women who want to get out of the gang life to go to work for the city, typically as landscapers, to earn a paycheck, find a new supportive community and leave The Life.

It doesn’t always work. Some try and don’t make it. The drop-out rate is high; it’s a constant struggle. But for the people who take, and keep, jobs in the program, the success rate is phenomenal.

“It’s pretty simple,” Cathey told me. “One hundred percent of the guys who get the jobs and go to work every day leave the gang life. One hundred percent of the ones who don’t show up for work, who don’t stick with it, go back to the gangs.”

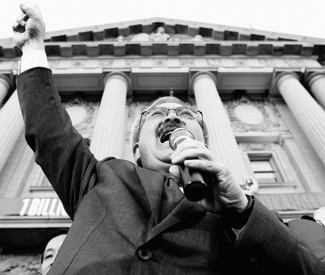

It’s a tiny project right now, involving maybe 20 people. Cathey and Sands, with the support of the brass at Mission Station and Chief Greg Suhr, are trying to expand it to reach kids as early as middle school, before the gangs get to them. They’ve rounded up a construction contractor who spent half his adult life behind bars, an ex-gang member, a City College administrator, and Supervisor David Campos, and, mostly under the radar, are trying to do what all the academics and professionals say is the only effective approach to this kind of crime. They’re trying to stop it before it happens.

********

One day about 18 months ago, Campos was walking down 24th Street, on his way to get a burrito for lunch, when a police car pulled over and two plainclothes cops got out. Campos represents the Mission, and previously served on the Police Commission, but he had never met Cathey or Sands. “I was surprised to see these two tough guys come up to me,” the supervisor recalled recently.

“They just stopped me and said, ‘supervisor, we need your help,'” Campos said. “They said they were tired of the cycle of putting kids in jail and seeing them come back out and do the same thing again, and they wanted to find an alternative. They asked me if I could get some gang members jobs.”

What the officers explained was simple, if counterintuitive: “The young men on the street are smart,” Campos told me. “They have a lot of skills to live the way they do. If they could put that into something constructive, they could be very successful.”

Campos gave the cops his card, told them to call his office — and an unusual relationship between one of the most progressive supervisors and two gang cops was born.

“It was crazy when I told my staff that we were going to be working in the Mission with law enforcement,” Campos said. “I’ve had people stop me and say, ‘Campos, what are you doing with the cops?’ But these guys are great, and they’re doing something really important.”

What the gang cops had in mind was this: If the city could offer jobs — outdoor, hands-on, get-your-fingers-dirty jobs — and Cathey and Sands could convince gang members to step away from the life and try working, there might be a way to end the violence.

The program would be tightly controlled: The two officers would invite gang members to apply for jobs, would screen them, and keep on top of every applicant. People who missed work, or screwed up on the job, would get a visit; Cathey and Sands would watch the streets, follow everyone in the program, check in with families — and let everyone know that their lives and futures were on the line.

“We started with one kid they knew,” Campos said. “We decided to see if we could find him a job.”

Campos contacted the Public Utilities Commission, which hires workers to do landscaping, and convinced the general manager, Ed Harrington, to give it a try.

Cathey and Sands went looking for the young man who would kick off the program (let’s call him J.), and wound up at his house, talking to his mom and dad. That would become a central part of their MO, involving the parents of gang members and trying to bring together what are sometimes not the closest of families.

It wasn’t an easy sell — the family didn’t trust law enforcement. “Then they told the dad that they were working with Campos, and their guard went down,” the supervisor said.

J. started working with the PUC, doing gardening and landscaping work. “He was so successful, nobody could believe it,” Campos said. “We went to see him later, and his dad said his life had completely changed. It changed the whole family.

“When we saw that, we decided we needed to expand this.”

From the start, Mission Station Captain Greg Corrales — a no-nonsense cop who is not known as a starry-eyed liberal — saw the logic and got behind his two officers. Chief Suhr also came on board.

In the early days, Cathey and Sands had no resources at all — not even money to get the young workers Muni or BART tickets. Campos helped track down the funding, and worked with the officers on the next group of kids.

“I bring them into my office at City Hall,” he said. “I explain that there’s a real responsibility here. You are going to change your life.”

********

I am sitting in the community room at the Mission Police Station, talking to two young men who Cathey and Sands have brought into the program. They’ve had some problems — missing work, hanging out with their old gangs — and they’re at risk of losing their jobs. Cathey is blunt: Keep this up, and you’re done. Keep this up, and you’re going back to the streets, back to the life you wanted to leave.

I tell the men I’m not going to print their names, and they agree to talk to me. It’s a dangerous situation — the gangs don’t like members dropping out, and really don’t like to see them at the police station working with the cops.

“Just walking in this door is a hard thing to do,” Cathey says.

But the two officers make it clear to everyone they meet — on the streets, in the program, and everywhere else: These kids are not snitches. “We don’t ask them to tell on their friends,” Cathey said. “I don’t do that, and I don’t want any part of it. This isn’t about us finding out information about the gangs, and that’s not why people come and see us.”

I ask the two young men about what their lives were like before they started working. They’re not interested in talking. When I ask straight out if they were gang members, they shrug, and change the subject.

But they’re happy to talk about their jobs and what it means to be employed. They’re bringing home a paycheck. They can help out their families. They’re also up early in the morning and really tired at night; the idea of going out with their old friends isn’t that appealing.

The handful of people who are working, and not showing gang colors, hasn’t stopped the violence in the e Mission. One of the kids in the program was shot and killed a few months ago. “It was heartbreaking,” Campos said. “I went to see the parents, and they told me how proud their son had been, how he was bragging about being the first one in the house up in the morning, how he loved his job.”

On the other hand, Campos noted, “There normally would have been retaliation for that shooting, and more killing. But the ones who might have retaliated were in our program, so it didn’t happen.”

********

The tech workers from Google and Apple and Facebook who are flooding into the Mission don’t see the signs on the street. Upscale white people who think the neighborhood is cool don’t tend to notice what’s happening in front of their eyes. There are at least 200 active gang members in the small piece of land bounded by Cesar Chavez, Potrero, Castro and 16th. As Cathey and Sands drive around, they see the colors everywhere.

North of 19th Street, the young men and women wear blue. They’re Surenos, southerners; many of them are recent immigrants. Cross 19th and the colors turn red; the Nortenos, who sport the number 14, control the south Mission. They tend to be born in this country.

Back in the 1960s, the two gangs emerged out of the state prison system; Surenos lived south of Bakersfield, Nortenos north. But these days, the geographic lines aren’t always as clear. “They’re really the same guys on both sides of the line,” Cathey explains. “Other than this blind loyalty, they’d probably get along.”

The gangs make their money selling drugs, and much of it eventually goes back to a handful of leaders, many serving long prison terms. Since a lot of the members either die or wind up incarcerated before they get out of their 20s, recruiting is constant.

“They have recruiters outside the middle schools,” Cathey tells me. “Last night we arrested a 15-year-old for possession of a handgun. They older guys made him hold it. Now his life is about to be ruined.”

The two cops are opposites: Cathey is ebullient, outgoing, a former tech worker who is constantly talking, texting and emailing. Sands is quiet, more taciturn, a martial artist who walks the streets with the look of serious business.

But they’re fast friends and partners who can communicate with a quick nod or shake of the head, and nothing in the Mission gets by them.

We pull up at 16th and Mission. “Just watch, the block will clear,” Cathey says. And yes, the minute the gang car is spotted, a guy in a blue hoodie ducks down into the BART station.

There’s a girl who can’t be 16 yet sitting on the bench. Sands hangs back while Cathey approaches her. He asks what she’s doing, what’s going on; she shrugs and ignores him. Not interested.

Cathey speaks with a bit of resignation as we walk back to the car. “She’s already jumped in” — initiated into the gang — he says. It’s going to be hard to reach the girl; the gang members she hangs out with are violent, armed, “and will come down on you in a second.”

It’s hard not to feel the frustration that comes with the territory: Violent and dangerous, maybe — but still, she’s still just a little girl.

We head up to 24th Street, Norteno turf. Here, when you look for it, red is everywhere. “A lot of these kids are living in crowded situations, in relatives houses,” Cathey says. “The gangs tell the young ones that they shouldn’t trust their families, that the gang is their new family. That’s what we’re up against.”

Two young men duck into a jewelry store. Cathey throws the car into park and the officers get out, walking slowly toward the entrance. The men with the red jackets and red highlights on their shoes know the drill. A quick warrant check and they know they’re free to go — but not without listening to Cathey for a few minutes.

This time, “The Speech” is falling on deaf ears.

Later, Cathey shows me a video he’s captured off YouTube. It’s hard to find, hidden under gang names that only insiders would know. It shows some of the guys we’ve seen on the street, beating the living shit out of people. In one scene, a handful of gang members approach a man, punch him in until he falls to the ground, then kick his head until he’s unconscious.

“This is what they do,” Cathey says. “They terrorize the neighborhood.”

********

I am back in the community room at Mission Station. Cathey and Sands have invited me to an “intervention.” A boy and a girl, both of them in eighth grade, are coming in, with their parents, to talk about their flirtations with gang life.

A counselor at James Lick Middle School contacted the officers after seeing signs that the kids were showing gang colors and drifting away from their schoolwork and their families. Cathey and Sands were at Lick a few months earlier, running an assembly and talking about the dangers of gangs; the counselor got their phone numbers.

I have agreed to use no names or in any way identify the participants in the intervention. So I sit and watch as Cathey runs the show.

The boy appears painfully young, small and shy; it’s hard to believe he’s even in eighth grade. He wears a hoodie and makes little eye contact with anyone else in the room. The girl is taller, more self-assured.

I can’t fathom that kids this young – the age of my own son, who is still shedding the soft edge of youth, sliding slowly into adolescence — are already prey to the gang recruiters. But the evidence is clear.

When the parents and other family members are seated, Cathey starts asking the boy about gang life. “What color do the Sureños wear?” Blue, the boy says. “What about the Norteños?” Red. “Where does Norteño territory start?” 19th Street. “What number do the Norteños associate with?” Fourteen. “Can you give me the street names of some gang members?” The boy rattles off a few.

Cathey looks over at the boy’s dad. “He knows a lot, doesn’t he?” The dad is visibly startled. So are the girl’s family members as the officers run through a similar routine.

“We’re seeing younger and younger kids get dragged in,” Cathey tells me later. Often, parents and grandparents — working multiple jobs to pay the rent in this rapidly gentrifying neighborhood — have little or no idea how far their kids have gone into the gang life.

Next up is Mike Bowen. He’s a soft-spoken guy whose face bears the scars of a hard life of substance abuse and jail time. In fact, he’s spent much of his adult life running from the law, winding up at one point jumping from a third-story window in a Tenderloin building to avoid arrest.

Two broken legs and months in the hospital put him on a path to sobriety — and a new life. “I used to think the money was in crime,” he tells the group. “Then I got myself together, went back to school, got my contractor’s license, and pretty soon I bought my first Lamborghini.”

That gets the young boy’s attention.

“You have so much going for you,” Bowen says. “You can make it.”

He turns to the boy’s mom, who speaks only Spanish, and asks her how it’s going. Not so great, she says; she just got laid off, and is having trouble finding a new job. Bowen reaches into his pocket and pulls out a stack of $100 bills. “Here, take this,” he says. “It will help until you find work.”

That really gets the boy’s attention.

Bowen’s been a key part of the two cops’ efforts, and they met entirely by chance. “I was driving down Folsom,” he told me. “I parked at a store and I saw these two cops, and I said hi and they wanted to check out my car, and we started to talk about my background. They told me what they were doing, and I said I’d love to help.”

Bowen offered money, which they needed, but that was just the start. “They brought me with them to James Lick,” he recalled. “I brought the Lamborghini. That got every one of the kids interested. I let them sit in it, then we talked.

“I told them that the gang members say the only way to get money is to join the gang. But I got out, went to school, and now I have a house and really nice car.”

When Bowen’s done with his talk, Cathey puts his cell phone on speaker and dials a number. The man on the other end is a former gang member. “He’s the real deal,” Cathey whispers to me. And indeed, for about ten minutes, he tells the two young people and their families exactly what their lives will be like if they follow the path he took at their age. By the end, the boy is shaken and the girl is crying.

Cathey’s not done yet. Guillermo Villanueva, a City College counselor, takes over and reads the families a pledge that Cathey and Sands have written. It’s all about family, about staying out of the gang life, but also respecting and taking care of each other. “Family and Education Forever” is the slogan, chosen because the gangs, who tell members that they are their new families, use “family forever.”

Yeah, the language in the pledge is a little bit hokey — but nobody’s laughing.

Cathey asks the boy what he wants from his parents. “I just wish my daddy had more time to play soccer with me,” he says. The officer looks at the father. “Every day, I’ll be there after work,” he says.

The pledge is on a plaque signed by Chief Suhr. Everyone signs it. By the end, there are tears and hugs all around.

“This is what we really need to be doing,” Cathey tells me. “Getting gang members to change is hard. If we can get them early enough, we have a much better chance.”

********

I’ve been a political reporter for 30 years. I write, mostly, about intractable social problems. I know that poverty and desperation lead to crime, that broken families and inadequate schools put young people at risk of falling into violence. I am under no illusions.

When I first heard about Cathey and Sands, I thought: They’re cops. Most of the time, cops aren’t the best answer to deep-seated social problems and the crime that results. And I’m not going to pretend that these guys are softies — you have a warrant out, you get caught in the act, they’ll pull you in, and it won’t necessarily be nice.

What they’re doing won’t end gang violence in San Francisco, not by itself. Everyone knows that. This is a huge issue, one that will become more and more pronounced as the crazy, ancient and pointless war between the Norteños and Sureños plays out in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood.

Cathey and Sands are by no means the only people fighting to end the carnage. Nonprofits, educators, social service agencies and others have spent years trying to break the gang cycle.

But there they are, every day, two guys with badges who see the blood and the pain on the streets, and are trying, with little bureaucracy or resources, to stop it. To save lives. One kid at a time.

“If we could get into all the middle schools, if we could expand this out, that’s what would really work,” Cathey told me. “That’s where we can have the biggest impact.

Crime would come down; it would have to.

“I’ve been trying to get a meeting with the mayor.” Paging Room 200, City Hall: Is anyone listening?