arts@sfbg.com

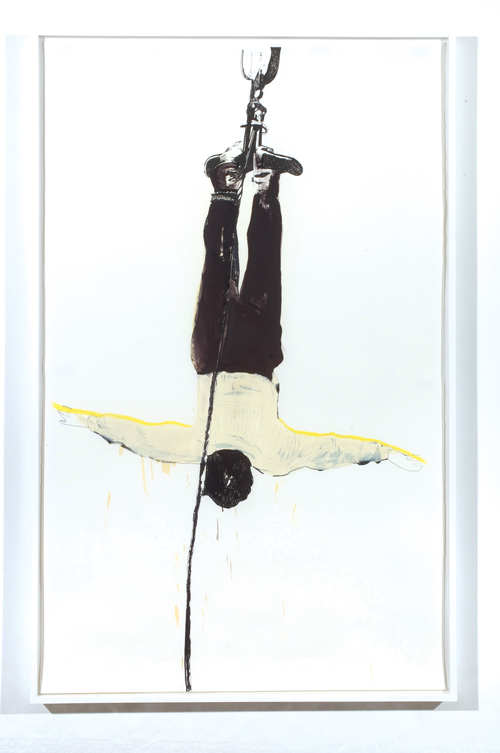

HAIRY EYEBALL/YEAR IN ART The year in art is ending on a note both sour and defiant. On Nov. 30, Smithsonian Secretary G. Wayne Clough, caving to criticism voiced by conservative politicians and religious groups, ordered the removal of David Wojnarowicz’s 1987 video A Fire in My Belly from the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture.” It was a cowardly decision; one that ultimately has undermined the credibility of Clough and his institution.

It’s unfortunate that it took an act of censorship to get art — specifically, art by an openly gay artist responding to the darkest hours of the AIDS crisis — back into the national conversation, but the chorus of condemnation coming variously from journalists and critics, art museum associations, and even The New York Times editorial page, has helped to do just that.

Additionally, Wojnarowicz’s piece, which was uploaded to Vimeo by his estate and New York’s PPOW Gallery soon after it had been taken down in Washington, D.C., has undoubtedly been seen by more viewers in the past month than it had at the Smithsonian, or perhaps even in past installations (as of writing this column, the uploaded version has received more than 18,000 views).

This will probably continue to be the case as more galleries and museums across the country, in an impressive show of institutional solidarity, screen and/or install A Fire In My Belly. Locally, SF Camerawork and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts held screenings earlier this month. Southern Exposure will continue to show the piece through mid-February, and SFMOMA is scheduled to screen the full-length version of the video in early January.

While I agree with Modern Art Notes’ Tyler Green that SFMOMA’s commitment to screen A Fire in My Belly is “a turning point” in this whole debacle (New York’s four biggest art museums have remained silent on the matter), I find his characterization of SFMOMA as “America’s most conservative, play-it-safe modern-and-contemporary art museum” a bit harsh. Certainly, this year’s recently revealed SECA winners — three of whom, it must be noted, have been past Goldie recipients, including 2010 winner Ruth Laskey — attest to the fact that, for every groaner of an exhibit (“How Wine Became Modern,” anyone?), SFMOMA is also committed to supporting artists whose work cannot be dismissed as “play-it-safe.” For starters, the memory drawings of Colter Jacobson, one of this year’s SECA winners, certainly fall along the continuum of queer portraiture displayed in “Hide/Seek.”

This is not to encourage wishful thinking. While it’s hard to imagine a San Francisco art institution doing something along the lines of the Smithsonian, I don’t think anyone expected a reignition of decades-old culture wars, let alone in the very city where the Corcoran Gallery infamously canceled a Robert Mapplethorpe exhibit in 1989. The shorter our cultural memory, it seems, the greater is our propensity to repeat the lowest moments of our history.

So, over the past few weeks, I’ve been going over the works, exhibits, and events that I was thrilled did happen here, all glorious reclamations of our Convention and Visitors Bureau’s tagline, “Only in San Francisco.” Here is an in no way complete rundown of some of the art I didn’t cover in this column for a variety of reasons (scheduling conflicts, in-the-moment preference, critical laxity), save for the works themselves.

L@TE, BERKELEY ART MUSEUM, MOST FRIDAY NIGHTS

Turning staid-by-day museums into hip nightspots for hip young folks has been the hip thing for institutions to do for some time now. Thankfully, the Berkeley Art Museum knows how to do it right. Skip the catered canapés and light show, and focus on programming that is truly varied and more often than not, locally-minded — from Terry Riley celebrating his 75th to Xiu Xiu frontman Jamie Stewart improvising film soundtracks, from performance artist Kalup Linzy singing dirty love songs to outré Mexican B cinema— all for next to nothing.

CARINA BAUMANN, UNTITLED (2) (2008-09), 2ND FLOOR PROJECTS, JAN.–FEB.

At first I couldn’t see the woman’s face in Carina Baumann’s Untitled (2). I stared into the slate-like surface (actually, translucent white film developed on aluminum), incrementally adjusting my height, until the blackness stared back. The effect was not one of shock, as with the mirrors at the end of Disney’s Haunted Mansion ride, in which the holographic undead crowd in with your reflection. Baumann’s art asks for patience and slow adjustment, and in return, regifts your sense of sight.

“SUGGESTIONS OF A LIFE BEING LIVED,” SF CAMERAWORK, SEPT.–OCT.

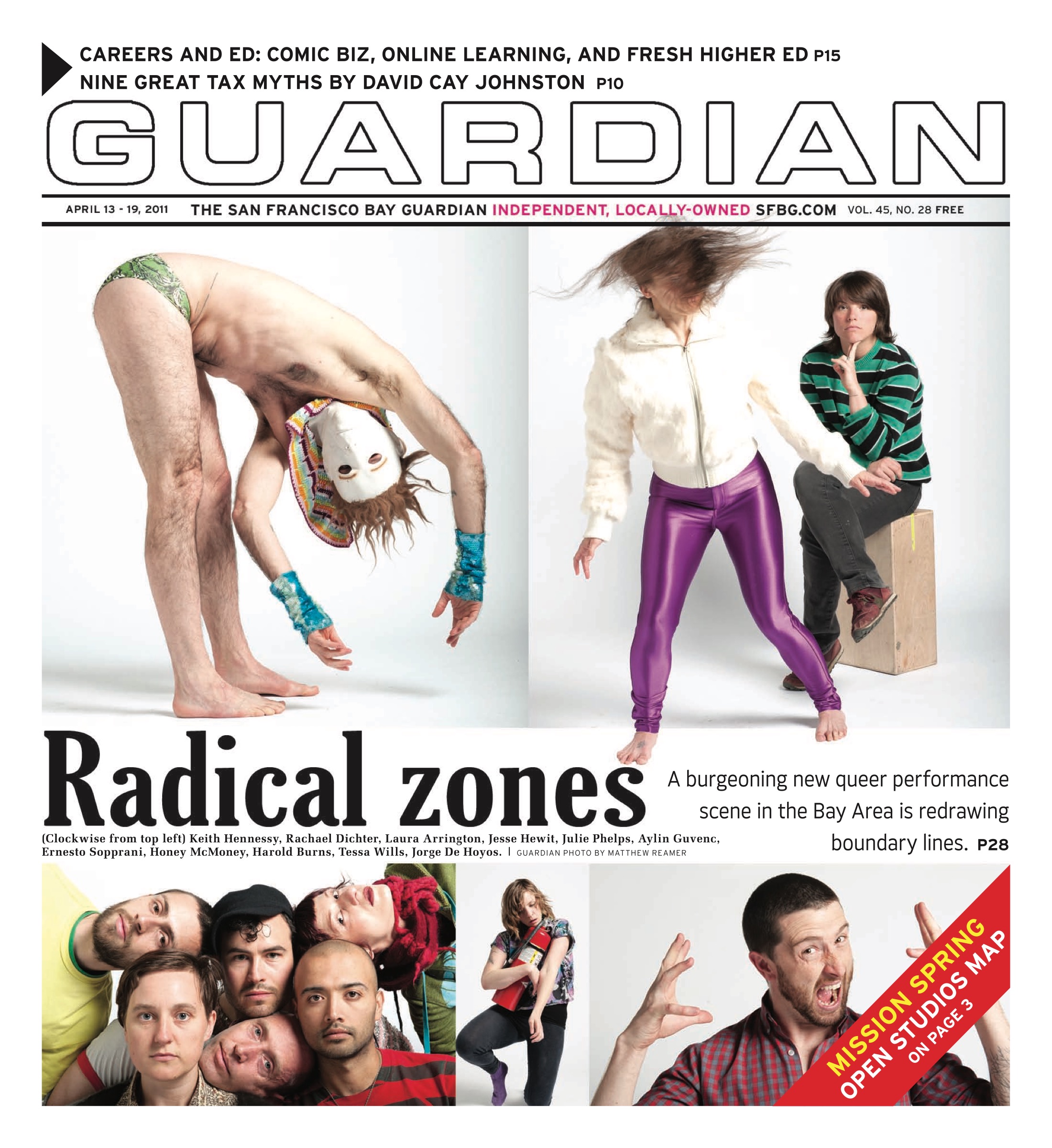

Perhaps most germane to the issues about queerness, identity politics, and representation now being raised (again) by Wojnarowicz-gate and the “Hide/Seek” exhibit, this group show put together by Chicago-based curator Danny Orendorff and SF native Adrienne Skye Roberts took “queerness” out into the desert, helped it cast off the much-tattered coat of identity politics, and asked a group of artists, activists, and filmmakers to record its unfettered visions of things to come (many of which, as the resulting work testified to, are being lived out right now).

MATT LIPPS, “HOME,” SILVERMAN GALLERY, APRIL-JUNE; R.H. QUAYTMAN, “NEW WORK,” SFMOMA, THROUGH JAN. 16, 2011

Although Matt Lipps is a photographer and R.H. Quaytman is a painter, they tweak their respective mediums in these unrelated shows to arrive at a similar kind of flat sculpture, which flickers between abstract prettiness and representational heavy-lifting. Lipps’ densely layered photographs of assemblages — in which variously colored photographs of domestic interiors, cut into facets and taped back together to form the original image, become backdrops for cut-out reproductions of Ansel Adams landscapes — collapse foreground and background, personal space and photographic history. Quaytman, working in dialogue with the poetry of Jack Spicer and SFMOMA’s photo archive, silk-screens images from the museum’s holdings onto beveled, wooden panels of various sizes, augmenting them with flashes of Easter eggs-like color and glittering crushed glass.

ERIK SCOLLON, “THE URGE,” ROMER YOUNG (FORMERLY PING PONG), JULY–AUG.

Although nothing will top his porcelain casts of assholes that littered Ping Pong Gallery like so many discarded sand dollars for the 2009 group show “Live and Direct,” Eric Scollon’s more recent solo exhibit at the gallery, “The Urge,” continued to queer form and function. The 50 or so small porcelain works, painted in the blue and white style of Dutch Delftware and arranged in pun-laden groupings, smartly played off ceramics’ dual cultural status as both a “fine art” and kitsch object, while throwing shade at modern art’s conflicted relationship to ornament. Speaking of which, if only I had a Scollon for my tree.

ANDY DIAZ HOPE, “INFINITE MORTAL,” CATHARINE CLARK GALLERY, THROUGH JAN. 1, 2011

Diaz Hope’s dazzling sculptures owe as much to his engineering background as to, as he puts it in an e-mail, a “revisiting of childhood thoughts about mortality and infinity.” Their mirrored, crystalline exteriors yell “Gaga!” but once immersed in their kaleidoscopic guts, they are, much like Yayoi Kusama’s infinity boxes, meditation chambers built from carnival ride components. Simply beautiful stuff.