rebecca@sfbg.com, joe@sfbg.com

It’s a simple fact of life: Money buys influence. But in San Francisco, despite strict sunshine laws to illuminate donations to city agencies and gifts to the regulators from the regulated, money still circulates in the shadows when it flows through the coffers of “Friends” in high places.

Major real estate developers, city contractors, and large corporations often lend financial support to San Francisco city departments, to the tune of millions of dollars every year. But the money doesn’t just flow directly to city agencies, where it’s easily tracked by disclosure laws. Instead, it goes through private nonprofits that sometimes label themselves as “Friends Of…” these departments.

They include Friends of City Planning, Friends of the Library, a foundation formerly known as Friends of the San Francisco Department of Public Health, Friends of SF Environment, and Friends of San Francisco Animal Care and Control.

The Friends pay for programs the departments supposedly cannot cover on their own. Bond money can build a skyscraper, but sometimes not fill it with furniture. Agencies are barred by law from funding an employee mixer or a conference trip, so departments turn to their Friends to fill in the gaps. Adding bells and whistles to city websites, holding lunchtime lectures, hiring a grant writer — or, in the case of the Department of Public Health, bolstering health services for vulnerable populations — these are all examples of what gets funded.

The extra help can clearly be a good thing, but the lack of transparency around who’s giving money raises questions — especially if it’s a business gunning for a major contract or a permit to build a high-rise.

City agencies receive outside funding from a wide variety of sources. Sometimes grants are made by the federal government, or a well-established philanthropic foundation — and according to city law, gifts of $10,000 or higher must be approved by the Board of Supervisors. But in the case of organizations like Friends, which are created specifically to assist city government agencies, the original funders aren’t always identifiable. And the collaboration is frequently much closer, with city staff members serving on Friends boards in a few cases.

Friends board members told the Guardian that their partnership with government helps bolster city agencies in a time of increasing austerity, in service of the public good. But do the special relationships these influential insiders hold with high-ranking city officials come into play when awarding a contract, issuing a permit, making a hiring decision, or determining whether a developer’s request for a rule exemption should be honored? Without more transparency, it’s tough to tell.

City disclosure rules state that any gift to a department must be prominently displayed on that department’s website, along with any financial interest the donor has involving the city. But Friends and other outside funders are under no obligation to share their supporters’ names, much less financial ties, when they distribute grants. Meanwhile, the disclosure rules that are on the books seem to be frequently ignored, misunderstood, or unenforced, our investigation discovered.

How are donors repaid for their support? Consider the controversy earlier this year around Pet Food Express, which won approval in June for another store in the Marina District despite opposition from four locally owned pet stores in the area that fear competing with a large national chain. Pet Food Express won the unlikely support of the city’s Small Business Commissioners, some of whom reversed their 2009 positions opposing the chain’s previous application.

SF Animal Care and Control Director Rebecca Katz personally lobbied the commission to support Pet Food Express, at least partially because the company has donated pet supplies valued at $50,000 to $70,000 per year to the department. That’s a lot of money for a cash-strapped city department, but a pittance compared to the profits of an expanding national chain.

It’s moments of clarity like those, when the public can easily trace the line from donations to political influence, that show why disclosure is so crucial. But those moments are few and far between when trying to trace the funders of private foundations and Friends organizations, where deals often happen in the dark.

WHEN DEVELOPERS ARE FRIENDS

At the Merchant Exchange Building in May, a crowd of high-profile real-estate developers mixed and mingled with city planners, commissioners, and even Mayor Ed Lee, wine glasses in hand. Sources told the Guardian that most of the planning staff was present, and not all were happy about having ribbons and name tags affixed to their shirts, as if they were being auctioned off.

With around 500 in attendance, the event was an annual fundraiser hosted by the Friends of San Francisco City Planning, a nonprofit organization that accepts contributions of up to $2,500 per individual to lend a helping hand to the Planning Department. This year’s event was titled “Incubator Startups, New Jobs for the Future,” hinting that the development community shares the mayor’s affinity for new tech startups and the droves of high-salaried IT professionals they’ve attracted to the city.

Some Friends of City Planning board members are major real-estate developers who routinely seek approval for major construction projects. Others are former planning commissioners, or have a background in community advocacy.

Amid widespread concern about displacement, gentrification, and the overall character of San Francisco’s built environment, no city department has greater influence than Planning. An individual’s interpretation of the Planning Code can carry tremendous weight; it’s a series of small decisions that shape a project’s profits and the look and feel of San Francisco’s future. And with cranes dotting the city’s skyline and market-rate construction catering to the wealthy while middle income residents get priced out, the amount of capital flowing through the development sector these days is astonishing.

In this dizzy climate, there might seem to be something askew about affluent developers and land-use attorneys rubbing elbows with city regulators, all eager to pass the hat for the Planning Department. Whiff of impropriety or no, the fundraiser appears to be totally legal.

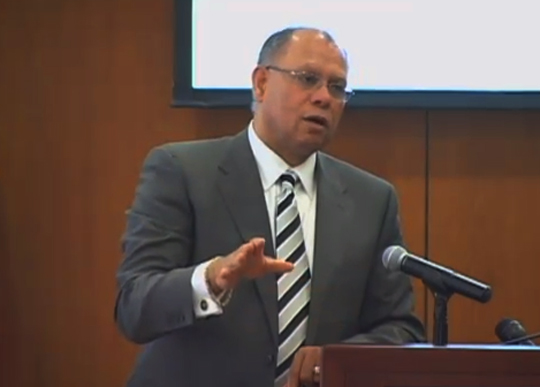

“We aren’t violating the law — that I know,” Friends of City Planning Chair Dennis Antenore told the Guardian. “We’ve had legal advice on that for years.”

There is close collaboration between Friends of San Francisco City Planning and the Planning Department — a partnership so entrenched that it’s almost as if the nonprofit is an unofficial, private-sector branch of the agency.

“We are certainly thankful and appreciative,” Planning spokesperson Joanna Linsangan told the Guardian. “They’ve helped us for many, many years.” The additional funding is needed, she said, because “there isn’t a lot of wiggle room” in the departmental budget.

Each year, Planning Director John Rahaim submits a wish list to the Friends, outlining projects he wants funding for. This year, he requested $122,000 for a variety of initiatives, including training support to help planners assess proposals for formula retail (read: chain stores). That’s a hot-button issue lately, and one that shows how seemingly small decisions by planners can have big impacts.

When the department’s zoning administrator ruled that Jack Spade, a high-end clothing chain that opened up in the old Adobe Books location on 16th Street, wasn’t considered formula retail and therefore didn’t need a conditional use permit, neither widespread community outrage nor a majority vote by the Board of Appeals could reverse that flawed decision. It was a similar story with the Planning Commission’s Oct. 3 approval of the 555 Fulton mixed use project, where Planning Department support for exempting the grocery store for the area’s formula retail ban made it happen, to the delight of that developer.

Even though the planning director makes specific funding requests each year to the Friends and pitches the projects in person at their meetings — and the Friends publishes a list of the grants it awards to the department online — the Planning Department is not reporting those gifts to the Board of Supervisors.

“I confirm that the Planning Department did not receive any gifts,” Finance and IT Manager Keith DeMartini wrote in official gift reports submitted to the Board of Supervisors for the years 2011-12 and 2012-13. Those reports were sent to the board on Oct. 7 and Oct. 4, respectively, well after the July filing deadline and after the Guardian requested the missing reports.

The Friends typically funds two-thirds of the requests, said board member Alec Bash, totaling around $80,000 a year. In 2012, the Friends awarded a $25,000 grant to make the department’s new online permit-tracking system more user-friendly, making life a lot easier for developers.

When asked what safeguards are in place to prevent undue influence when the director is soliciting funding from a nonprofit partially controlled by developers, Linsangan responded, “those are two very separate things. One does not influence the other.”

She stated repeatedly that planners are not privy to information about individual contributors — but the fundraisers are organized by a board that includes identifiable developers, and anyone who attends can plainly see the donors in attendance. Nevertheless, Linsangan insisted that planners would not be swayed by this special relationship, saying, “That’s simply not the way we do things around here. We do things according to the Planning Code.”

But as the ruling on Jack Spade shows, as well as countless rulings by planners on whether a project is categorically exempt from the California Environmental Quality Act, interpreting the codes can involve considerable discretion.

The public can’t review a list of who wrote checks to the Friends of San Francisco City Planning for the May fundraiser. Since the organization waits a year between collecting the money and disbursing grants, donors stay shielded from required annual disclosures in tax filings.

But Antenore says the system was established with the public interest in mind. “We don’t reveal the contributors, because we don’t want anybody to have increased influence by a donation,” he insisted. Bash echoed this idea, saying the delay was to “allow for some breathing room.”

Unlike some of his fellow board members from the high-end development sector, Antenore has a history of being aligned with neighborhood interests on planning issues, helping author a 1986 ballot measure limiting downtown high-rise development. He emphasized that the developers on the Friends board are balanced out by more civic-minded individuals.

Still, developers who regularly submit permit applications for major construction projects sit on the Friends board. Among them are Larry Nibbi, a partial owner of Nibbi Bros.; Clark Manus, CEO of Heller Manus Architects; and Oz Erikson, CEO of the Emerald Fund development firm.

“We’re not making use of [the funding] in a way that benefits these people,” Antenore said. “I wouldn’t do this if I thought otherwise. I have been careful to maintain the integrity of this organization.” The money is meant to facilitate better planning, he added. “I don’t think there’s any conspiracy,” he said. “We’re not financing anything evil.”

Both the Planning Department and its Friends dismissed the idea that the donations could open the door to favoritism or undue influence. So why isn’t the department reporting gifts it receives from the Friends to the Board of Supervisors, or disclosing them on its website, as required by city law?

According to a 2008 City Attorney memo on reporting gifts to city departments, when an agency receives a gift of $100 or more, it “must report the gift in a public record and on the department’s website. The public disclosure must include the name of the donor(s) and the amount of the gift [and] a statement as to any financial interest the contributor has involving the city.”

John St. Croix, director of the San Francisco Ethics Commission, confirmed that’s the current standard, telling us, “The actual disclosure should be on the website of the department that received the gift.”

Linsangan said records of the gifts are indeed available — listed as “grants” in the department’s Annual Report. But while the 2011-12 report lists grants from sources such as the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Environmental Protection Agency, there was no mention of Friends of City Planning.

The memo also says any gift of $10,000 and above must first be approved by a resolution of the Board of Supervisors. But last year, when the Friends provided $25,000 to upgrade the permit-tracking system, it wasn’t sanctioned by a board resolution. Asked why, Linsangan made it clear that she was not aware of any such requirement.

As is common, when it comes to adhering to disclosure laws, confusion abounds. And sometimes, only sometimes, politicos get caught.

READING UP ON DISCLOSURE LAWS

When the head of a city agency fails to report gifts totaling $130,000, how much do you think he is fined?

City Librarian Luis Herrera failed to report receiving that amount in gifts and he was fined exactly $600 by the California Fair Political Practices Commission on Sept. 19. Specifically, Herrera had to file a form 700 with the FPPC to state the gifts he received. From 2008-2010, the forms he turned in had the “no reportable interests” box checked.

The money was used in what he calls the City Librarian’s Fund, which is the money he keeps on hand to pay for office parties and giving honorariums to poets and speakers who perform at the library’s branches, money that wasn’t disclosed on the very forms designed for reporting it.

There are two stories of how the fine came about. Longtime library advocate James Chaffee said that it was the result of a complaint he filed with the FPPC in April, and indeed, he sought and obtained many public documents revealing the money trail. San Francisco Public Library spokesperson Michelle Jeffers disagreed, saying that the fine was the result of an ongoing conversation with the FPPC to figure how exactly to file the gifts appropriately.

“The law wasn’t clear around these forms and it wasn’t clear if he had to report them,” she told the Guardian. “For amending the reports you have to pay a $200 fine for every year it was proposed. We keep scrupulous records on every pizza party we have.”

When government officials receive “gift of cash or goods,” they must report them annually in statements of economic interest, known as a Form 700, to the city Controller’s Office. The form is kind of a running tally of who is receiving gifts from whom, a way for the public to track money’s influence in government.

The gifts came from the Friends of the San Francisco Public Library, another nonprofit that bolsters city agency funding. Now Herrera has to list the $130,000 gifts from fiscal years 2008-09 and 2009-10 on his website.

What exactly does that accomplish? As it turns out, not a whole lot.

City Administrative Code 67.29-6 defines the reporting of gifts to city departments, and one of those requirements is to make a statement of “any financial interest the contributor has involving the city.” Now that Herrera lists the Friends of the San Francisco Public Library as donors on the department website, the statement of financial interest by the friends group is this: “none.”

There are myriad donors to the Friends of the SFPL, and the group doesn’t have to state the economic interests of its donors, or even mention who its donors are. The code requires gifts be reported to the controller, and the deputy city controller told us this doesn’t apply to the “friends of” organizations, or any nonprofit foundation arms of city departments.

“If gifts are made to a department, yes, they have to disclose, so people don’t get preferential interest in getting city contracts,” Deputy Controller Monique Zmuda told us. “I know it’s a fine line. The foundations don’t provide us with anything.”

Friends of the SFPL doesn’t provide money just for pizza parties. A breakdown of a funding request from the library to its Friends shows requests up to $750,000 to advertise the library on Muni and in newspapers, funding for permanent exhibits, and the City Librarian’s personal fund. That’s just the money it gives to the library. Other monies are spent directly on activities supporting the library.

As Jeffers pointed out to the Guardian, the money isn’t spent on “trips to Tahiti.” Friends of the SPL do good city works, from a neighborhood photo project in the Bayview branch library to providing books for children. But the question is: Who’s buying that goodwill and why?

The millions of dollars in donations made to the Friends of the SFPL don’t need to be approved by the Board of Supervisors, like gifts to departments do. They’re not checked for conflicts of interest or financial interest by any governmental body. Donors give and the Friends of SFPL spend freely, financial interest or not.

When our research for this story began, no financial statements were available of the Friends of the SFPL website. After a few days of inquiries, the most recent year’s financial statements from 2011-12 were posted to the website.

Ultimately, the San Francisco Public Library is one of the smaller city departments, with an annual budget that hovers around $86 million. The Department of Public Health is a much bigger beast, with a 2011-12 budget of around $1.5 billion.

One of its main foundations, the San Francisco General Hospital Foundation, is also one of the largest nonprofits that supplements city spending. In many ways, it could be described as the model of disclosure for city foundations, although its disclosures are not by law, but by choice.

FOUNDATION OF FRIENDS

The Department of Public Health relies on a few entities that fundraise on its behalf: the San Francisco Public Health Foundation, the Friends of Laguna Honda Hospital, and the San Francisco General Hospital Foundation.

“They’re private nonprofit entities that are separate from the department,” CFO Greg Wagner told us. “But their roles are to support the department in its efforts.” He cited examples such as sending its staff to conferences or hosting meetings, “things that we don’t have the budget for or don’t have the staff or resources.”

The lion’s share of the DPH’s gifts are funneled through the SFGHF. Unlike many of the assorted Friends groups or foundations that support city services, the SFGHF extensively reports the sources of its $5 million in donations. The donors include a veritable who’s who of San Francisco: the Giants, Sutter Health, Xerox, Pacific Union, and Kohl’s all donated between $1,000 and $10,000 in the past two years.

But the largest gifts to the SFGHF came from Kaiser Permanente, and its financial interests in the city run deep. Kaiser came into the city’s crosshairs in July, when the Board of Supervisors passed a resolution calling on Kaiser to disclose its pricing model after a sudden, unexplained increase in health care costs for city employees. Kaiser holds a $323 million city contract to provide health coverage, and supervisors took the healthcare giant to task for failing to produce data to back up its rate hikes.

In the meantime, Kaiser has also been a generous donor. It contributed $364,950 toward SFGHF and another $25,000 to SFPHF in fiscal year 2011-12.

The funding from Kaiser and a host of other contributors — which include Chevron, Intel, Genentech, Macy’s, Wells Fargo (another city contractor), and a pharmaceutical company called Vertex — does support needed programs. They include research into the health of marginalized communities, services through Project Homeless Connect, screening for HIV, and immunization shots for travelers.

But because DPH doesn’t count much of this support as “gifts” formally received by the city, it isn’t subject to prior approval by the Board of Supervisors, or posted on the department’s website along with the contributors’ financial interests. Major contributions are disclosed in a report to the Health Commission, something Wagner described as a voluntary gesture in response to commissioners’ requests.

“Most gifts to foundations are donations to a nonprofit and do not come through the city or DPH at all,” he noted.

This distance is maintained on paper despite close collaboration with the department. In the case of Project Homeless Connect, a program that holds a bimonthly event to aid the homeless, it supports programs headquartered in city facilities. Penny Eardley, executive director of SFPHF— which used to be called Friends of San Francisco Public Health — noted that her organization occasionally makes grants or seeks funding in response to department requests. And Deputy Director of Health Colleen Chawla is a foundation board member. It’s almost like these foundations are extensions of the department, except they’re not.

SFPHF also earns revenue as a city contractor. When DPH received a grant from the Centers for Disease Control, it contracted with SFPHF to manage subcontracts with about a dozen community-based organizations.

The web gets even more tangled. The president of SFPHF is Randy Wittorp — who’s also Director of Public Affairs for Kaiser Permanente’s San Francisco Service Area. It’s a similar story with SFGHF, whose board includes several General Hospital administrators, including CEO Susan Currin.

Former Health Commissioner James Illig said people shouldn’t worry, that hospital the staff would never direct foundation funds to pet projects or mishandle funds. “They maintain a separation and a firewall,” he said, for example noting, “Sue Currin is not directing funds to her own hospital.”

But he did admit that since SFGHF’s minutes are not public documents, that “raises a few concerns,” arguing the public should be able to inspect financial documents to decide if the foundations are directing funds lawfully to city departments.

Even when the public by law has a right to access financial records of a city department, rooting out corruption can be like pushing a boulder up a San Francisco hill.

FROM PATIENTS TO PARTIES

In 2010 and 2011, Laguna Honda Hospital administrators and staff used money from the hospital’s patient gift fund to throw a party. And then they spent it on airfare. And then they gave laser-engraved pedometers to the staff. All told, they spent nearly $350,000 meant for the dying and the infirm, nearly half of the total funds.

The incident was big, messy, and out in the public eye. It was an all-too-rare glimpse into the shady use of public funds by public officials. But when hospital staff members Dr. Derek Kerr and Dr. Maria Rivero blew the whistle on Laguna Honda’s misuse of patient funds in 2010, they were drummed out of their jobs.

Eventually litigation on behalf of the whistleblowers and their complaints of corruption were found to have merit.

Kerr’s vindication came at a meeting of the Health Commission in April 2013. In the packed City Hall meeting room, the public watched as Laguna Honda Executive Director Mivic Hirose read her apology to Kerr and Rivero aloud, even announcing a plaque in Kerr’s honor.

“The hospital will install the plaque in the South 3 Hospice,” she read, stiltedly, from a written statement, surrounded by microphones at the podium. “The plaque will say: In recognition of Derek Kerr MD of his contributions to the Laguna Honda’s hospice and palliative care program 1989-2010.”

Kerr received a settlement of $750,000 and something more important: His good name cleared.

But that conflict of interest was rooted out only after years of litigation that revealed the financial abuse through legal discovery of the department’s documents — documents that should’ve been public in the first place. ABC 7’s I-Team broke the story and did much of the reporting at the time, otherwise the entire affair may have been swept under the rug.

The misuse of funds was only brought to light with the revelation of public documents — revelations not possible with most Friends groups. The Laguna Honda Hospital Foundation has also had financial dealings with potential conflicts and a lack of transparency.

The now-defunct LHHF’s board chair, former City Attorney Louise Renne, made an interesting choice for her vice chair after she formed the nonprofit in 2003. Derek Parker was vice chair of the LHHF while simultaneously heading architecture firm Anshen-Allen, with a $585 million city contract to rebuild the hospital.

So he was not only rebuilding Laguna Honda under city contract, but soliciting and spending donations meant to supplement his project. Renne wrote to the Health Commission in December 2011 that LHHF’s purpose was to manage over $15 million in donations meant to furnish the hospital with beds, chairs, and other necessities. Eventually, then-Mayor Willie Brown found funding for the hospital, reducing the foundation’s role.

In a phone interview with the Guardian, Renne said the goals of the LHHF were only ever to furnish the newly christened hospital. “Our purpose was to fill the void, if you will, for what the city and its services could not do,” she said.

But in her letter, Renne advocated for LHHF to take an active role in fundraising for the hospital for years to come. “Today, the members of the Board of Directors of the Foundation continue to assist the hospital in various phases of its new projects and operations with projects approved by the City and/or the hospital administration,” she wrote to the Health Commission.

And Parker would have potentially managed millions of dollars flowing through donations for countless other hospital projects, while heading an architectural firm with contracts to build in San Francisco. We were unable to reach Parker for comment.

“I never saw Derek use his position as an architect or position for any political gain, I never saw it,” Renne told us. But no one else would see it either, because organizations like the now closed Laguna Honda Hospital Foundation operate without public oversight.

The Health Commission itself even noted this in its March 2012 meeting, the minutes describing then-commissioner James Illig as critiquing the foundation for not being open about its source of funding.

“Commissioner Illig thanks Ms. Renne and Mr. Parker for coming to the Commission,” the minutes read. “Because (LHHF) is a project of Community Initiatives, a fiscal sponsor for nonprofits, it is not possible to find basic financial information about the Foundation or its activities.”

Due to a quirk of her foundation being under the “umbrella” of a separate entity, Community Initiatives, Illig was never able to even get the LHHF’s IRS forms, he told us. “We tried to get information and reports, and the Community Initiatives [Form] 990 was giant,” Illig said. “It didn’t separate anything out.”

Illig told us that it made sense to have Parker on the board because he is monied and well connected, making it easier to solicit donations. But insiders close to the board told us that Parker’s position may have made it easier to swing getting other contracts for his firm.

Parker got another city contract building the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital at Mission Bay, slated to open in 2015. No doubt his firm got the job partly due to his reputation as pioneering architecture that leads to healthy patient outcomes — but then again, the board he served on also approved donations to research at UCSF.

Laguna Honda Hospital Foundation may now be defunct, but it serves to illustrate the lack of controls and oversight of the foundations beyond even gift disclosure.

OFF THE BOOKS

It might be characterized as a web of influence, cronyism, or just the way business is done. But is there something improper about all of this?

Private funding often represents a needed boost that allows for important work to take place beyond what could happen under ordinary budgeting. At the same time, it smacks of privatization. While departments and funders point to lean times in the public sector to justify the need for this help, the funding continues to flow whether it’s a good year or a bad year for city government. And at the end of the day, the most glaring issue of all seems to be the lack of transparency.

Are city departments ever tempted to bend the rules to lend a little help to their Friends? As long as the funding is in the dark, the public has no way of knowing.

Ethics chief St. Croix told us his office lacks the resources to visit every city website and check up on whether departments are following the disclosure rules. “If someone brought it to my attention that a department received a gift and didn’t post it [on the website],” he said, “we would look into it.”

But if the watchdogs need watchdogs, citizens who can’t even review documents that should be publicly available, then these quasi-governmental functions and the people who fund them will remain in the shadows.

Danielle Parenteau contributed to this report.

ADDENDUM

When city funders operate in the dark, one of the best ways to learn about corrupt influence, misuse of funds, and other transgressions is from whistleblowers. If you have a tip for us, send us snail mail at SAN FRANCISCO BAY GUARDIAN, 225 Bush, 17th Floor, San Francisco, CA 94104. Or email us at news@sfbg.com. Just make sure not to use an email address provided by your workplace, which is less secure.