steve@sfbg.com

May Day, also known as International Workers Day, began in the United States, but it’s been all-but ignored by most Americans for decades. And on this May Day, 2013, in the city of San Francisco, it’s a good time to note that the growing wealth and income gaps between the rich and the rest of us are reaching historic highs — a dangerous situation, many economists warn — and hardly anyone at City Hall is talking about it.

The job boom in San Francisco, much touted and promoted by Mayor Ed Lee, has been largely in the tech sector, which has created great wealth. But some economists are starting to argue that the Internet, rather than creating economic and political democracy, has done just the opposite.

We’re talking about more than just high rents and gentrification — the industrial sector that San Francisco is pinning its future on, critics say, is one of the most brutally monopolistic and exploitive in modern history. It should come as no surprise that the Bay Area has among the highest income and wealth inequality in the nation.

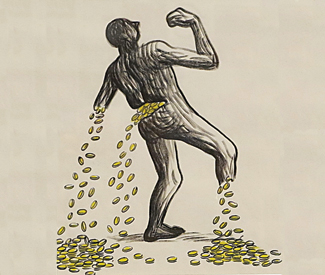

There’s no shortage of data pointing to growing inequality and the danger that it poses, but the bottom line is that hoarding of wealth by the rich is causing the middle class to shrink and to make it harder for those on the bottom to just get by.

“About 6 in 10 of us believe that the tax system is unfair — and they’re right,” Nobel-laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz noted in a recent New York Times column. “Put simply, the very rich don’t pay their fair share,”.

But Americans generally don’t understand how bad things really are. Polling done by Harvard and Duke University researchers in 2010 found most Americans vastly underestimate this country’s wealth gap (most thought the top 20 percent controlled 59 percent of the country’s wealth, rather than the true figure of 84 percent), and overwhelmingly preferred far more economic equity (most respondents thought it would be fair for the top fifth to control 32 percent of the wealth, which is the case in Sweden).

Part of the misunderstanding comes because “the economy” of the wealthy is doing great, even if that doesn’t help most Americans. “The stock market is basically back to where it was in 2000, while corporate earnings have doubled since then. Yet the real median wage is now 8 percent below what it was in 2000, and unemployment remains high,” UC Berkeley Professor Robert Reich, another leading voice on the issue, wrote on his blog last month.

“Most of the Western world has experienced an increase in inequality in recent decades, though not as much as the United States has,” Stiglitz wrote. “But among most economists there is a general understanding that a country with excessive inequality can’t function well.”

GEN Y, X, HIT HARDEST

The wealth divide is not only growing, but it is impacting young people and minority groups particularly hard, and with that concentration comes the potential for social instability and unrest.

The growing divide between the rich and the rest of us is being felt most acutely by Hispanics and African Americans, according to a new report by the Urban Institute, “Less Than Equal: Racial Disparities in Wealth Generation.”

In 2010, white families earned about $2 for every $1 earned by black and Hispanic families, a ratio that has held steady for about 30 years. But an even more important and telling figure is the gap in wealth, which includes savings, investments, and home values minus total debts. Before the recession that began in 2008, white families had four times the wealth of black and Hispanic families. That ratio widened to 6-1 by 2010. The most recent figures show the average wealth of white families is $632,000, compared to $98,000 for black families and $110,000 for Hispanic families. The reasons range from inheritances to tax policies skewed in favor of the wealthy, such as mortgage deductions and low taxes on retirement savings and capital gains.

“The federal government is subsidizing asset building and it’s going to high-income people,” Caroline Ratcliffe, a senior fellow at Urban Institute who helped write the study, told the Bay Guardian.

She called that policy dangerously short-sighted because it causes social ills such as crime and poverty, as well as putting a damper on future economic growth, which in this country relies on consumer spending by a strong middle class.

Ratcliffe also helped produce an Urban Institute study that came out last month, “Lost Generations? Wealth Building among Young Americans,” which showed how Generations X and Y — those under 40 years old — are in worse shape and have far fewer opportunities to build wealth than previous generations.

“Their average wealth in 2010 was 7 percent below that of those in their 20s and 30s in 1983,” the study states. “Even before the Great Recession, young Americans were on a strikingly different trajectory. Now, stagnant wages, diminishing job opportunities, and lost home values may be merging to paint a vast different future for Gen X and Gen Y. Despite their relative youth, they may not be able to make up the lost ground.”

The situation is even worse is supposedly prosperous California. A November 2011 study by the California Budget Project, “A Generation of Widening Inequality,” found that “a disproportionate share of income gains in recent decades has accrued to the very top of the distribution, in spite of continued productivity gains.”

A big reason for the disparity is policies that tax work at higher rates than investments, which make up a significant portion of wealthy people’s income. The top 5 percent of California taxpayers made 54.5 percent of their incomes from work and 42 percent from investments (and 3.5 percent from retirement income), compared with the bottom 95 percent of Californians, who made 80.8 percent of their income from wages and 11.3 percent from retirement income.

Among the 50 states, California ranked seventh in income disparity, between Alabama and Texas. Among urban areas in the US, the Bay Area has the seventh highest income disparity in the country. Economists and historians say such inequities aren’t sustainable, and they are bound to put pressure on the political system whose policies created them. As Ratcliffe concluded: “We need our federal leaders to focus more on these disparities.”

Or, as San Francisco economist Peter Donohue put it, “We’re moving toward a moment when the opportunity to restructure American politics is approaching. I’m content to be patient and watch things come apart this year.”

And San Francisco — a rich city with glaring and growing economic inequities, where city policies continue to subsidize technology companies backed by wealthy investors even though unemployment is low and the cost of living is rising steeply — could be one of the places where things begin to come apart.

THE IRONY OF TECHNOLOGY

In many ways, the technology sector has played a cruel hoax on the American people. Computer technology promised to expand the economy, increase productivity, and democratize society. Instead, it has helped downsize the US workforce, made the average person work harder for stagnant wages, and accelerated the decline of the media, unions, and democratic institutions, replacing them with a cacophony of bloggers and often powerless voices drowning in a sea of idle chatter.

True, the Internet and related technologies did generate wealth and prosperity — but economic data since the dawn of the Worldwide Web clearly shows that prosperity has not been broadly shared. Instead, the Internet — along with the illusory ideals of libertarian individualism its biggest backers support — has helped usher in the biggest consolidation of wealth since the Gilded Age.

Robert McChesney is a communications professor at the University of Illinois who has written several books on the relationship between democracy and our increasingly corporate-controlled media. His new book, Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet against Democracy, examines how technological and political changes have consolidated wealth and power.

McChesney said that 20 years ago, the Internet was presented to the public as “the mightiest weapon ever against inequality, both political and economic inequality,” a message still sounded by its biggest boosters. But instead, he noted that almost half of the largest corporations in the US got that way by monopolizing technology sectors and gobbling up smaller competitors.

“One of the great ironies of the Internet is it is one of the greatest creators of economic monopolies in history, bar none,” he told the Guardian.

Whether it’s Google, Facebook, Airbnb, or Twitter, he said the leaders in any realm of technological innovation become the de facto gathering spots for consumers — and the corporations then use that market power to kill off any would-be competitors, a reality that extends from the globalized virtual world into the localized real world.

“It has eliminated the ability to have local alternatives,” he said.

McChesny is no fan of Mayor Lee’s embrace of tech-centered economic development.

“It’s tragic, it’s pathetic, it’s outrageous, it’s obscene — but it’s also what you’d expect,” McChesney said. “This is they world we live in, one of extraordinary monopolies. These companies are so large that it’s a new Gilded Age. And they have nothing to fear from the government, even when they blatantly rip people off.”

The other great irony of the Information Age is how the investor class has appropriated for itself the worker productivity gains enabled by technology. Nowhere is that more true that with tech workers themselves, who tend to work longer than legal hours creating tools that increase productivity — which should allow us to work fewer hours.

The economic data clearly shows that the average American has been working steadily more hours for at best stagnant wages since the 1970s when the country’s prosperity was last shared in an equitable way across classes. And technology companies themselves, and the tax laws that govern them, are some of the worst examples of the problem.

“They are produced largely by companies with intangible assets, and they produce intangible assets, so it’s largely under the radar…People don’t understand that intangible assets are often far greater than real assets,” said Donohue, noting that everything from the venture capital funds that fuel Internet start-ups to the patents and intellectual property they produce largely escape taxation, particularly here in California (whereas Oregon, Florida, and other states do tax some intangible assets, such as the money tied up in investments). “California has a tax code that has gone out of its way to exempt intangible assets.”

McChesney and others do think things are slowly changing, with the old lies and deceptions getting less believable as economic hardships get more widespread and the monopolies stifle innovation, a process that he said has already begun.

“The start-up phase of the Internet is slowing down,” said McChesney, whose book documents that trend, which is attributable to everything from patent law to the unfair competition of monopolies. “This system isn’t working and most people are being dealt a bad hand,” he told us, noting that many polls show the people are ahead of political and economic leaders on the understanding the issue. “But it is a declining system, a decaying system…Something has to give. You can’t have the continuation of corruption at the political level and the economic damage it does and not have a backlash.”