arts@sfbg.com

PERFORMANCE Some dramatic clouds hung darkly over the Headlands Center for the Arts on the last Sunday in March, threatening more than the prickly spray that had started to whip around in the cold and gusty air. By contrast, everything was bright and bustling inside Building 944, the repurposed 1907-era military barracks at the center of the Marin County artists retreat’s secluded, picturesque coastal campus. The first-floor dining hall was still open until 3 p.m. — when the latest edition of SQUART was scheduled to begin upstairs — so arriving audience members gravitated to the long tables lining the unexpectedly beautiful room, revivified from spartan army drabness by artist Ann Hamilton.

Uncle Sam was not anticipating this crowd in 1907, let alone the anarchic spirit of creative community fostered by SQUART (short for spontaneous queer art). Then and now, Uncle Sam wants “you,” but not your yoke-slipping imagination please. The performers running around loopy for lack of sleep — together with the center’s varied flock of international resident-artists and the crowd arriving from the city to watch the results of SQUART’s 24-hour venture in collaborative art-making — formed an alternative community, low-key and self-assured, the majority queer-identified, well-versed in strategies of critical resistance and up for anything. In striking ways, the four performance pieces communally created for that afternoon — and for that history-haunted place — eloquently registered the gaps and links in a century of social chaos.

All told, a moment from the last piece was probably my favorite. In a large first-floor room elegantly and eccentrically composed like something from a Peter Greenaway film, a good chunk of the audience had been pressed to the wall by a relentlessly advancing line of screaming men and women with their arms outstretched. Then a man rushed to the window and (with a vaguely camp bellicosity) ordered a small group of performers out the windows and up the hill. There in the cold drizzle they stood on the access road in shorts and tees, doing exercises, as two of the performers began to wrestle aggressively.

This “fight” inspired an unwitting passerby to come between them with real violence, as the audience gasped loudly in surprise and alarm at the unscheduled event. The good Samaritan, flushed and angry, cocked a confused glance at the audience of maybe 60 people filling the windows, and trudged back to his car and family and drove away, visibly shaken. The performance continued, in fact did not miss a beat, the performer at the window shouting a beautiful broken monologue full of yearning, confusion, and wonder interspersed with loud calls to “Retreat!” that sent the performers scrambling up the slippery hillside in the rain, bare limbs flailing, helpless, comical, and heartbreaking.

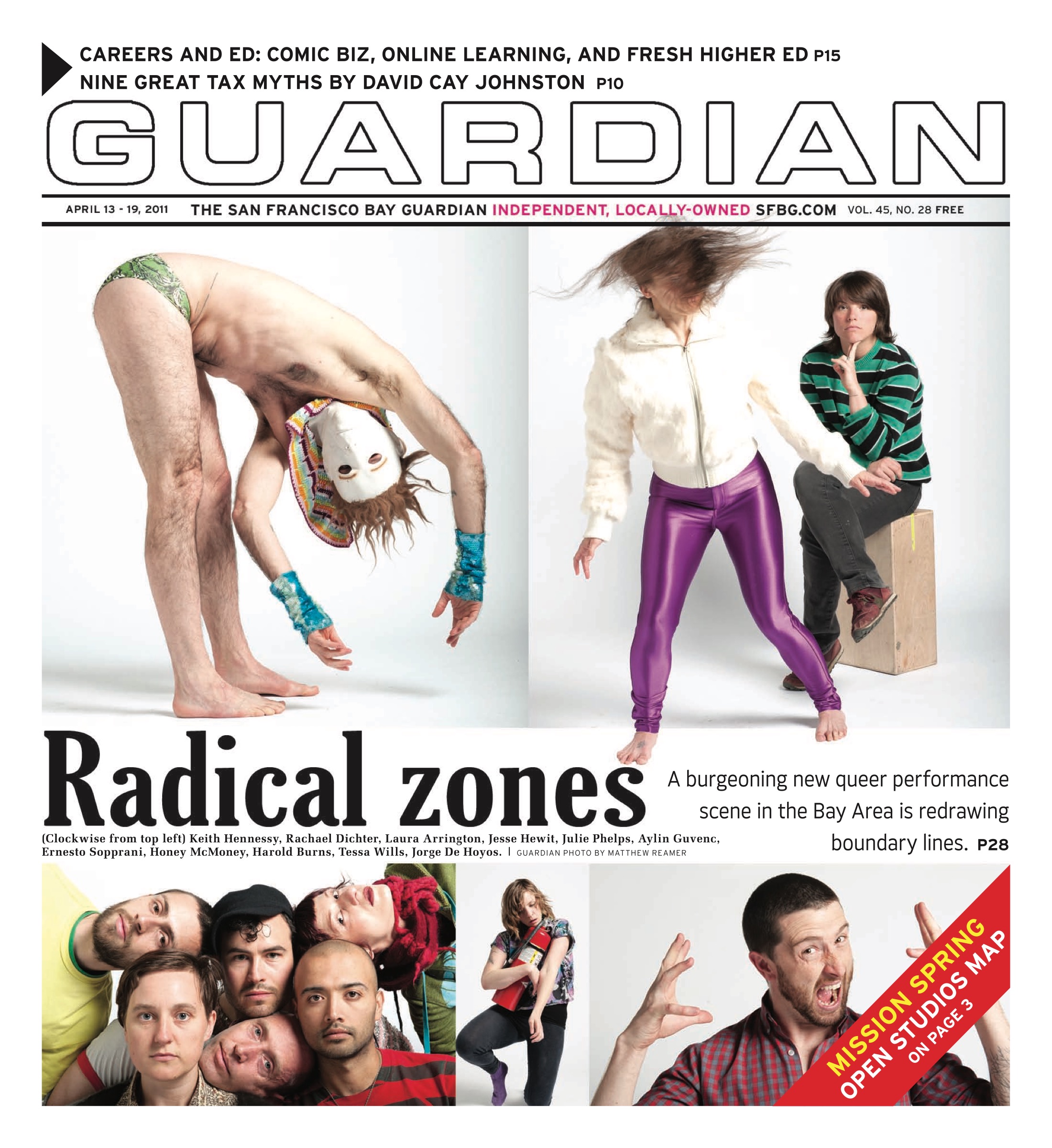

SQUART is the initiative of San Francisco–based choreographer Laura Arrington, one of a new generation of mostly queer artists under or around 30 who are making serious waves in the performance scene. Her own bounding, sharp-cornered, mercurial work has been staged at CounterPULSE (where she shared a much acclaimed bill with fellow artist-resident Jesse Hewit in August of 2010), Women on the Way, the National Queer Arts Festival, The Lab, and the Too Much! queer performance marathons. But SQUART is a unique undertaking in which the artist functions as a channel for collaborative expression. As such, it both epitomizes and catalyzes the current queer performance movement as a whole.

SQUART also epitomizes a community and an ethic of DIY art production that is on the rise just now across a range of insider/outsider artists in the Bay Area. It’s a generational movement, but at the same time it’s building on, and building relationships with, earlier generations of artists. It’s predominately queer, but genuinely inclusive; it’s DIY, but skilled and knowing; it’s anti-institutional but includes many with practical and critical training from university programs; and it’s been producing some of the most appealing, challenging, vital work in performance in the last few years. It’s a highly fertile scene that, taken as a whole, amounts to a movement and a rare moment.

Modeled on reality-TV talent contests — but in opposition to the social Darwinism normally on display there — SQUART gives random teams of artists a set of parameters and two hours to come up with an original performance piece. A panel of “celebrity judges” from the wider arts community evaluates the results. The results have been surprising enough to participants and audiences alike to keep SQUART going through several iterations since its 2010 inception, always with the quick and affable Arrington as the host sporting her now trademark bullhorn.

“It began out of a sincere desire to get people working together and to get ideas out,” says Arrington about SQUART’s origins. “I’m suspicious of how isolating working can be — with grants, residencies, artist statements, etc. — how everything is ‘my project,’ ‘my work.’ I think ideas get better the more they are bounced around, and that stripping away the traditional hierarchies is important. It’s dangerous when work becomes precious. [With] SQUART, you just have to create. There’s no time to do anything else. It can be a big mess; often it’s a really beautiful mess.”

Arrington says SQUART started as a side project but has developed into something larger. “The Headlands SQUART was a big step,” she says, crediting program director Brian Karl with open-minded support of the undertaking. “We kind of took over the main building for 24 hours. It was crazy, but in the end some of the work was just staggering. The timing was pretty magical too. We got [choreographer] Meg Stuart [as a celebrity judge] because she was in town doing Auf Den Tisch! at Yerba Buena [Center for the Arts], and Big Art Group [Caden Manson and Jemma Nelson] happened to be up at Headlands while I was. Jess Curtis is back for a few months from Berlin. It was all quite perfect.”

The coincidental calendar-pairing of SQUART and Auf Den Tisch! (which means “to put things on the table”) was a striking alignment of the leading, established international contemporary performance represented by Berlin-based American Stuart and the new but internationally aware local scene. In making her long-overdue Bay Area debut (courtesy of YBCA), Stuart not only brought a project exploring the nature of collective improvisation, but drew performers from a local artistic milieu that included emerging queer performers like Julie Phelps and Jorge De Hoyos.

Keith Hennessy, the renowned interdisciplinary artist and performance maven who was both a performer and organizer for Auf Den Tisch!, says there are similarities between Stuart’s improvisation project and SQUART.

“In some ways, the Auf Den Tisch! project is like a weeklong SQUART, with a much tighter selection of who’s in it. There’s a certain camp in contemporary dance and performance that was born out of really early queer theater, like Theater of the Ridiculous and Jack Smith, and that came to some people through performance art. I see that in both SQUART and Auf Den Tisch!“

But Hennessy adds a key distinction. “Auf Den Tisch! is more about improvisation than SQUART,” he points out. “In SQUART you have to use improvisational strategies to survive, but it’s actually about collective composition, which is really kind of amazing.”

Hennessy — who was among the celebrity judges at the Headlands SQUART — has been a motive power himself in stitching together this younger generation of artists. Dancer/performer Harold Burns says he moved here from the East Coast partly inspired by Hennessy’s work, “the idea of merging queer and radical with powerful performance that really broke boundaries.” Burns joined workshops Hennessy led in November 2009 in the lead-up to Hennessy’s anniversary season (workshops that would inspire the two annual Too Much! queer marathons). Burns calls those workshops an important catalyst in the development of the community and its momentum. “The relationships were already there,” he explains, “but it personalized them more and took them to the next level.” Arrington agrees. “I met a lot of the people I consider close personal friends and colleagues there. After that, Jesse [Hewit] and I (with our friend Hana Erdman) started a little workshop/experiment where we tried to gather collaborators with similar interests.”

For his part, Hennessy got introduced to many of the younger artists through his participation judging earlier SQUARTs. In fact, SQUART and its larger community have been acquiring the regard of older, more established colleagues in a relatively short time.

David Szlasa can concur. “When I judged SQUART in October, there were 50 incredibly talented people making work who I barely knew,” confesses the artist and programming director at Z Space (which, significantly, will be presenting new work by Laura Arrington and Jesse Hewit on its massive stage in December). “I realized the 20-something crew just came to town, and they’re kicking ass.”

Szlasa credits SQUART with opening his eyes to the recent shift in approach as well. “One of the things that distinguished [the new work] was its nonreliance on the institution. SQUART is a hugely successful, hugely popular thing put together through Facebook.” For Szlasa, committed arts presenters like CounterPULSE and Z Space go only so far in explaining the success being enjoyed by artists like Arrington and Hewit or other of their peers.

“It’s artists who are being built up on the support of a community,” Szlasa notes, “rather than artists looking to institutions to find the support in the community for their work, which is a really different thing. It might be a small community that they’re rallying, but it’s significant. Maybe it’s 200 people and they all see everything everybody does, but, you know, that’s a thing. And it appears to be a mindset change also, which I really appreciate. And I think that there’s something for us — I say “us” as a representative of Z Space or that sort of institution — to consider and learn from that.”

CounterPULSE’s Jessica Robinson Love agrees. “These artists are not just interested in getting their own work out there. Most of them are also engaged in curating and producing each other’s work, serving as dramaturge, writing about it, and generally working to support the community and not just themselves. That’s where the strength comes from.”

MAMA’S BIG HOUSE

In any preliminary mapping of the scene, such as the piece you are reading, SQUART is only one point of reference, albeit a prominent one. At the very least, one would need to include now-defunct Mama Calizo’s Voice Factory, which for three years, under Dwayne Calizo, consistently supported exceptional work by queer artists, especially queer artists of color, in the old Jon Sims Center for the Arts space.

Just as crucial has been Mama Calizo’s still venue-less but highly active successor organization, THEOFFCENTER, whose director Ernesto Sopprani helped organize and run the SQUART event at the Headlands. In fact, TOC includes a good swath of the community. Says artist and codirector Julie Phelps, “THEOFFCENTER rose from the dust [as] a loose collective of 20 to 30 people who just keep showing up, and keep making things happen.”

You’d also need, for sure, to include Philip Huang’s Home Theater Festival, BJ Dini’s anarchist-inspired QAZ (queer autonomous zones); venues like CounterPULSE and The Garage as well as their residency programs; mentoring and collaborating queer performance elders like Hennessy, Jess Curtis, and Monique Jenkinson; the drag series led by Mica Sigourney; and a broad and often highly political host of outsider warehouse and home-based queer performance, as well as music-based work, across San Francisco and the East Bay.

“The artists in our network are making work without permission or money,” says THEOFFCENTER’s Sopprani. “We support one another and let the work and the questions motivating it speak for themselves. Laura Arrington’s SQUART is the perfect example of that credo. Laura is a genius when it comes to building synergy. We support her work because we feel it supports the larger community. In both SQUART and TOC, artists are autonomous and free. It’s a loose collective with the intention and desire to make something out of the ordinary happen. At the end of the day, that’s what it’s all about for us.”

HOME IS WHERE THE ART IS

The Dana Street Theater is an inconspicuous venue, serving most of the year as Philip Huang’s bedroom. In the first week of March, prospective patrons were alerted to upcoming performances by a blog site and a piece of yellow notepaper taped to the front door of his Berkeley apartment building, where some hasty red lettering announced, “Home Theater Festival. ‘Eat, Pray, Tron.'”

The audience for the opening show of the festival — and there were about 30 of us the night I went — sat in a tight squeeze on the floor, camped on cushions or blankets. Huang greeted people as they came in. No reservations were necessary. The prices were $7.99 a ticket, or $4.99 if you’re down on your luck. The scheduled curtain time was 8 p.m., though by the time Huang returned from a last-minute beer run it was more like 20 minutes after the hour. No one cared about the time, or that it seemed Huang hadn’t really bothered to pick up his room before the show. Even before the malt liquor and box wine started circulating, the audience was primed.

The monthlong, second annual Home Theater Festival is Huang’s Internet-orchestrated DIY affair. (And newly international: the same day I saw “Eat Pray Tron,” people Down Under attended a program at Rebecca Cunningham’s pad in Brisbane, Australia. In all, five countries and 30 shows are represented.)

Huang began in character as Ellen Fu, a bracingly frank Taiwanese lady in a black sleeveless number and clip-on earrings. Ellen led a seminar on how to pleasure your black lover. There was more: a disabled man making balloon animals, for instance. Huang was sharp but loose, ready to go with the moment. There was a lot of back-and-forth with pal Bryan Dini of the League of Burnt Children and the aforementioned QAZ. Seated sublimely against a wall, Dini interjected commentary as the mood struck him. Later in this carefree, careening, and irresistible evening, Huang paused for a special message to artists: “You have everything you need to do what you do right now,” he told them. “You have everything you need to be happy.”

The DIY spirit of Home Theater Festival, and of the larger movement it’s part of, couldn’t have asked for a more eloquent summation — or one that hinted so neatly at its radical response to a larger context of economic crisis and control. Huang is a charismatic figure, quick-witted and generous, lanky and handsome in thick-framed glasses and a beaming smile. He’s a fearless, unflappable performer and activist (some of his interventions are documented in must-see YouTube videos). He also makes the most outspoken people sound awfully tactful.

“I think most arts institutions, galleries, foundations, and theaters are useless,” he says. “They keep artists in a state of dependency; they encourage a mindset that they hold all opportunities and paths to legitimacy and artists are only ever on the receiving end. That’s why they keep putting out tired workshops and seminars that teach people to do lame shit like write grants and fundraise and network and do marketing and write press releases. All of that shit makes my dick limp, and none of it is necessary.

“I, in particular, believe that queer artists should not be professionals,” Huang explains. “We should burn bright and burn out. We have a responsibility to society as a whole to scare the shit out of people. We should be the monsters they accuse us of being. Every society needs to enact its shadows, and it’s our sacred duty, our sacred function, to do that for the world.”

Huang argues the fulfillment of that function, the fulfillment of a truly subversive art, necessarily takes place outside of institutions. “Institutions, for the most part, are run by fearful, well-meaning people, to apply a phrase by Kirk Read, and to keep their heads above water, they can never really disturb the status quo. So I encourage queers to break away from institutions for their own independence, certainly, but also to restore queer art to its grimy gutter.”

“This is quite a topic at the moment,” acknowledges Arrington when I ask her about the DIY-versus-institution issue. “For myself, I like hybrid situations. I will always have house shows and do the less structured stuff, but I also love rigorously worked art. I love high production value. In my experience, most institutions are made up of incredibly hard-working people sincerely trying to nurture art. SQUART happening at Headlands is a great example. It’s a totally nontraditional format happening in quite a traditional space.” At the same time, she insists, “institutional success is not all there is. I think, actually I know, bigger issues of politics, economics, and environment are going to reshape how art gets made, both inside and outside institutions.”

Jesse Hewit agrees that the issue of institutional support has become a serious dividing line, though he finds positive aspects to the debate as well. “People are really talking about this right now. On the one hand there’s this group of people, myself included, who are working in conjunction with Angela Maddox over at YBCA curatorially to mobilize the community [around] what’s going on in an international scene in terms of contemporary performance. And there are a lot of people who feel at odds with that. There’s this weird tension.” Hewit notes the change has occurred over the last six months: “The big love fest is over. People are getting more critical, which is good. It’s good for the work. The work has been becoming more excellent.”

Hewit suggests the uneven distribution of funding among the larger community plays some part in the increased tension, which seems all but inevitable, but he also cites a resistance to engaging an international context for contemporary performance. “We’re just not a super savvy contemporary performance/dance community,” he admits. At the same time, he appreciates the invention and novelty of the work being done on its own terms: “We’re doing our own thing. We’re kind of creating our own mini canon.”

Hennessy echoes the notion that the work is generally growing stronger, wherever it may stand with respect to funding. On the anti-institutional side, he stresses the shrewdness in something like the Home Theater Festival. “Part of it is an empowerment strategy,” he says, pointing out that Huang’s project grew from Huang’s experiments with private performances, which granted him—despite a lack of formal training or connections—the permission to consider himself an artist. “He took that personal experience and is using it as almost a viral infection,” says Hennessy. “The Home Theater Festival is simultaneously a super sophisticated aesthetic strategy and an amateur hour—anyone can do whatever they want and it’s not precious. It’s just in your house and it’s 20 people and they paid $7.99.”

Hennessy stresses that this is more than just a theoretical move. “There are all these practical things: no middleman, a really accessible door price, money goes directly to the artist.” In a society that easily dismisses artist labor, Hennessy sees the Home Theater Festival “starting to rebuild this broken bond between the artist and society by making everything really transparent, inviting people into your home. I think all the issues around private and public are really fascinating [and] very much inspired by certain feminist issues that have come to be in the foreground of what queer is. There’s all kinds of lineage in that.”

Wherever the contradictions and tensions may ultimately lead, this continues to be an exciting moment across a range of contemporary performance in the Bay Area. For its part, THEOFFCENTER is looking ahead to their second season with a conviction born of early but impressive successes many can rally behind. Sopprani says TOC will be pushing work “that integrates the arts and artists across platforms and communities.” His examples include Killer Queen: The Story of Paco the Pink Pounder, a show about a gay boxer that will be staged in actual boxing rings in San Francisco and Los Angeles; and Taylor Mac’s The Lily’s Revenge, in which TOC comes on board as a community partner in the Magic Theatre’s much anticipated Bay Area premiere.

“We are hoping to stick around for the long term,” says Sopprani, marveling at all they’ve accomplished thus far. “It’s amazing what comes out of putting the artist first. Entire houses continue to get filled. People are liking what they see, and I am very proud of us all.”

Special thanks to Mark McBeth (markmcbethprojects.com) for his invaluable “field recordings in performance anthropology,” which gave audiovisual access to some of the performances and artists drawn on for this article.