steve@sfbg.com

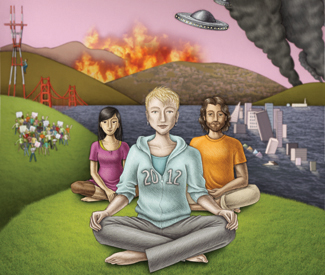

It’s easy to dismiss all the hype surrounding the auspicious date of December 21, 2012. There’s the far-out talk of Mayan prophecy and the galactic alignment. There’s the pop-culture lens that envisions the apocalypse. There are the extraterrestrials, about to return.

But even the true believers in Mayan folklore and its New Age interpretations say there’s no end of the world in sight. Time doesn’t end when the Mayan cycle concludes; it’s actually a new beginning.

And even some of the most spiritually inclined on the 12/21 circuit agree that it’s highly unlikely that anything of great moment will happen during this particular 24-hour period in history. The sun will rise and set; the winter solstice will pass; we’ll all be around to see tomorrow.

In fact, instead of doomsday, the most optimistic see this as a signpost or trigger in the transformation of human consciousness and intentions. Their message — and it isn’t at all weird or spacey or mystical — is that the world badly needs to change. And if all the attention that gets paid to this 12/21 phenomenon reminds people of what we have to do to save the planet and each other, well — that’s worth getting excited about.

Check out the news, if you can bear it: Global warming, mass extinctions, fiscal cliffs, social unrest. Now stop and turn the channel, because we’re also writing another story — technological innovation, community empowerment, spiritual yearning, social exploration, and global communication.

Both ancient and modern traditions treat the days surrounding the solstice is a time for reflection and setting our intentions for the lengthening, brightening days to come. And if we take this moment to ponder the course we’re on, maybe the end of the world as we know it might not be such a bad thing.

THE LONG VIEW

The ancient Mayans — who created a remarkably advanced civilization — had an expansive view of time, represented by their Long Count Calendar, which ends this week after 5,125 years. Like many of our pre-colonial ancestors whose reality was formed by watching the slow procession of stars and planets, the Mayans took the long view, thinking in terms of ages and eons.

The Long Count calendar is broken down into 13 baktuns, each one 144,000 days, so the final baktun that is now ending began in the year 1618. That’s an unfathomable amount of time for most of us living in a country that isn’t even one baktun old yet. We live in an instantaneous world with hourly weather forecasts, daily horoscopes, and quarterly business cycles. Even the rising ocean levels that we’ll see in our lifetimes seem too far in the future to rouse most of us to serious action.

So it’s even more mind blowing to try to get our heads around the span of 26,000 years, which was the last time that Earth, the sun, and the dark center of the Milky Way came into alignment on the winter solstice — the so-called “galactic alignment” anticipated by astrologists who see this as a moment (one that lasts around 25-35 years, peaking right about now) of great energetic power and possibility. The Aztecs and Toltecs, who inherited the Mayan’s calendar and sky-watching tradition, also saw a new era dawning around now, which they called the Fifth Sun, or the fifth major stage of human development. For the Hindus, there are the four “yugas,” long eras after which life is destroyed and recreated. Ancient Greece and early Egyptians also understood long cycles of time clocked by the movement of the cosmos.

Fueled by insights derived from mushroom-fueled shamanic vision quests in Latin America, writer and ethnobotanist Terence McKenna developed his “timewave” theories about expanding human consciousness, using the I Ching to divine the date of Dec. 21, 2012 as the beginning of expanded human consciousness and connection. And for good measure, the Chinese zodiac’s transition from dragon to snake also supposedly portends big changes.

In countries with strong beliefs in myth and mystical thinking, there’s genuine anxiety about the Dec. 21 date. A Dec. 1 front page story in The New York Times reported that many Russians are so panicked about Armageddon that the government put out a statement claiming “methods of monitoring what is occurring on planet Earth” and stating the world won’t end in December.

Here in the US, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was also concerned enough about mass hysteria surrounding the galactic alignment and Mayan calendar that it set up a “Beyond 2012: Why the World Won’t End” website and has issued press statements to address people’s eschatological concerns.

So what’s going to happen? There are authors, scholars, and researchers who have devoted big chunks of their lives to the topic. Two of the most prominent are Daniel Pinchbeck, author of 2012: The Return of Quetzacoatl and star of the documentary film 2012: A Time for Change and John Major Jenkins, who has written nearly a dozen books on 2012 and Mayan cosmology over the last 25 years.

“I never proposed anything specific was going to happen on that date. I think of it as a hinge-point on the shift,” Pinchbeck told me.

But there are those who hope and believe that the end of 2012 marks an auspicious moment in human evolution — or at least that it represents a significant step in the transformation process — and they seem fairly patient and open-minded in their perspectives on the subject.

“The debunking type isn’t some rational skeptic. They are true believers in the opposite,” Jenkins said. “We don’t know what’s going to happen. We’ve been filtering 2012 through some kind of Nostradomus filter.”

Jenkins and others like him have been clear in stating that they aren’t expecting the apocalypse. Instead, they emphasize the view by the Mayans and other ancient thinkers that this is a time for renewal and transformation, the dawning of a new era of cooperation.

“I think the Maya understood that there are cycles of time,” Jenkins said. “2012 was selected by the Maya to target this rare procession of the equinoxes.”

If the ancients had a message for modern people, it was to learn from our observations about what’s going on all around us. As Jenkins said, “They recognized their connection to the natural world and the connection of all things.

ACHIEVING SYNTHESIS

Many Bay Area residents are now headed down to Chichen Itza, Mexico, where the classic Mayans built the Pyramid Kukulkan with 365 faces to honor the passing of time — and where the Synthesis 2012 Festival will mark the end of the Mayan calendar with ceremonies and celebrations.

“It’s probably one of the most pointed to and significant times ever,” Synthesis Executive Producer Michael DiMartino told me, noting that his life’s work has been building to this moment. “As a producer, I’m very focused on the idea of spiritual unity and events with intention.”

DiMartino told me he believes in the significance of the galactic alignment and the ending of the Mayan calendar, but he sees the strength of the event as bringing together people with a wide variety of perspectives to connect with each other.

“We’re at a crossroads in human history, and the crossroads are self-preservation or self-destruction,” he said. “Synthesis 2012 is the forum to bring people together into a power place.”

Debra Giusti, who is co-producing Synthesis, started the Bay Area’s popular Harmony Festival in 1978, and co-wrote the book Transforming Through 2012. “Obviously, the planet has been getting out of balance and there is a need to go back to basics,” Giusti told me.

They are reaching out to people around the world who are doing similar gatherings on Dec. 21, urging them to register with their World Unity 2012 website and livestream their events for all to see. “We are launching this whole global social network to help develop solutions,” DiMartino said. (You can also follow my posts from Chichen Itza on the sfbg.com Politics blog).

Two of the keynote speakers at Synthesis 2012 are a little skeptical of the significance of the Mayan calendar and the galactic alignment, yet they are people with spiritual practices who have been working toward the shift in global consciousness they say we need.

“It’s more of a marker along the way,” Joe Marshalla, an author, psychologist, and researcher, told me. “We’ve been in this transition for almost 30 years.”

Marshalla said his speech at the festival will be about using certain memes to focus people’s energy on creating change, starting with letting go of the thoughts and structures that divide us from each other and the planet and replacing them with a new sense of connection.

“Everyone is waking up to the deeply held knowledge of the one-ness of all the planet, that we are in this together,” Marshalla said. “I think the world is waking up to the fact there are 7 billion of us and there are a couple hundred thousand that are running everything.”

Caroline Casey, host of KPFA’s “Visionary Activist Show” and a keynote speaker at the Synthesis Festival, takes a skeptical view of the Mayan prophecies and how New Age thinkers have latched onto them. “Everything should be satirized and there will be plenty of opportunities for that down there,” she said, embracing the trickster spirit as a tool for transformation.

But the goal of creating a new world is one she shares. “Yes, let’s have empire collapse and a big part of that is domination and ending the subjugation of nature,” she said. Rob Brezsny, the San Rafael resident whose down-to-earth Free Will Astrology column has been printed in alt-weeklies throughout the country for decades, agrees that this is an important moment in human evolution, but he doesn’t think it has much to do with the Mayans.

“My perspective on the Mayan stuff tends to be skeptical. It might do more harm than good,” Brezsny told me. “It goes against everything I know, that it’s slow and gradual and it takes a lot of willpower to do this work.”

READING THE STARS

The ancient Maya based their calendar and much of their science and spirituality on observations of the night sky. Over generations, they watched the constellations slowly but steadily drifting across the horizon, learning about a process we now know as precession, the slight wobble of the Earth as it spins on its axis.

Linea Van Horn, president of the San Francisco Astrological Society, said there is something simple and powerful about observing natural cycles to tap into our history and spirituality. “All myth is based in the sky, and one of the most powerful markers of myth is precession,” she said.

DiMartino said it wasn’t just the Maya, but ancient cultures around the world that saw a long era ending around now. “They each talk about the ending and beginning of new cycles,” he said. “Prophecies are only road signs to warn humanity about the impacts of certain behaviors.”

Casey’s a bit more down-to-Earth. “This has nothing to do with the galactic center,” Casey said, decrying the “faux-hucksterism” of such magical thinking, as opposed to the real work of building our relationships and circulating important ideas in order to raise our collective consciousness.

Van Horn has been focused on this galactic alignment and its significance for years, giving regular presentations on it since 2004. “The earth is being flooded with energies from the galactic center,” she said.

Issac Shivvers, an astrophysics graduate student and instructor at UC Berkeley, confirmed the basic facts of the alignment with the galactic center and its rarity, but he doesn’t believe it will have any effect on humans.

“The effect of the center region of the galaxy on us is negligible,” he said, doubting the view that cosmic energies play on people in unseen ways that science can’t measure. In fact, Shivvers said he is “completely dismissive” of astrology and its belief that alignments of stars and planets effect humans.

Yet many people do believe in astrology and unseen energies. A 2009 poll by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life found that 25 percent of Americans believe in astrology. A similar percentage also sees yoga as a spiritual practice and believes that spiritual energy is located in physical things, such as temples or mountains.

This moment is really about energy more than anything else. It’s about the perception of energies showering down from the cosmos and up through the earth and human history. It’s about the energy we have to do the hard work of transforming our world and the vibrational energy we put out into the world and feel from would-be partners in the process ahead.

“If you’re a liberal person without a spiritual grounding, it does look pretty bleak,” Pinchback said, noting the importance of doing the inner work as the necessary first step to our political transformation.

And both Casey and Brezsny believe in rituals. “Humans have been honoring the winter solstice for 26,000 years,” she said. “Every winter solstice is a chance to say what is our guiding story that we want to illuminate.”

GLOBAL TIPPING POINT

The world is probably not going to end on Dec. 21 — but it could end in the not-too-distant future for much of life as we know it if we don’t change our ways. Humans are on a collision course with the natural world, something we’ve known for decades.

In the last 20 years, the scientific community and most people have come to realize that industrialization and over-reliance on fossil fuels have irreversibly changed the planet’s climate and that right now we’re just trying to minimize sea level rise and other byproducts — and not even with any real commitment or sense of urgency.

The latest scientific research is even more alarming. Scientists have long understood that individual ecosystems reach tipping points, after which the life forms within them spiral downward into death and decay. But a report released in June by the Berkeley Initiative in Global Change Biology has found that Earth itself has a tipping point that we’re rapidly moving toward.

“Earth’s life-support system may change more in the next few decades than it has since humans became a species,” said the report’s lead author, Anthony Barnosky, a professor of integrative biology at UC Berkeley.

While the Earth has experienced five mass extinctions and other major global tipping points before, the last one 11,700 years ago at the end of the last ice age, Barnoksy said, “today is very different because humans are actually causing the changes that could lead to a planetary state shift.”

The main problem is that humans simply have too big a footprint on the planet, with each of us disturbing an average of 2.27 acres of the planet surface, affecting the natural world around us in numerous ways. The impact will intensify with population growth, triggering a loss of biodiversity and other problems.

“The big concern is that we could see famines, wars, and so on triggered by the biological instabilities that would occur as our life-support system crosses the critical threshold towards a planetary-state change,” Barnosky said. “The problem with critical transitions is that once you shift to a new state, you can’t simply shift into reverse and go back. What’s gone is gone for good, because you’ve moved into a ‘new normal.'”

Barnoksy said he’s not sure if the trend can be reversed, but to minimize its chances, humans must improve our balance with nature and avoid crossing the threshold of transforming 50 percent of the planet’s surface (he calculates that we’ll hit that level in 2025, and reach 55 percent by 2045). That would require reducing population growth and per-capita resource use, speeding the transition away from fossil fuels, increasing the efficiency of food production and distribution, better protection and stewardship of natural areas, and “global cooperation to solve a solve global problem.”

His conclusion: “Humanity is at a critical crossroads: we have to decide if we want to guide the planet in a sustainable way, or just let things happen.”

Perhaps it’s not merely a coincidence that our knowledge of the need for a new age is peaking in 2012. “It’s not surprising the world is in a crisis as we approach this date,” Jenkins said. “I don’t know how it works, but there is a strange parallel with what the ancient Maya foresaw.”

But the change that we need to make isn’t about just buying a Prius, composting our dinner scraps, and contributing to charities. It requires a rethinking of an economic system that requires steady growth and consumption, cheap labor, unlimited natural resources, and the free flow of capital.

“Basically, we are going to have to have a rapid shift in global consciousness,” Pinchbeck said. “You would not be able to create a sustainable economy with the current monetary system. It’s just not possible.”

Yet to even contemplate that fundamental flip first requires a change in our consciousness because, as Pinchbeck said, “We have created a stunted adult population that isn’t able to think in terms of collective responsibility.”

Brezsny said humanity shouldn’t need a galactic alignment or Mayan prophecy to feel the compelling need to take collective action: “I can’t think of any bigger wake-up call than to know that we’re in the middle of the biggest mass extinction since the dinosaur age.”

What comes next is really about how humans use and guide their energies, or as DiMartino said, “We, through our actions and intentions, create the world and take the path that we are creating.”

CATASTROPHISM HAS LIMITS

It may be the end of the world as we know it, but sounding that warning may not be the best way to motivate people to action, according to a new book, Catastrophism: The Apocalyptic Politics of Collapse and Rebirth.

Two of the book’s authors — Sasha Lilley, a writer and host of KPFA’s “Against the Grain,” and Eddie Yuen, an Urban Studies instructor at the San Francisco Art Institute — recently spoke about the limits of catastrophism as a catalyst for political change at Green Arcade bookstore.

Christian conservatives have long sounded the apocalyptic belief that Jesus will return any day now. Yet Lilley said those on the left have had a long and intensifying connection to catastrophism — “seen as a great cleansing from which a new society is born” — based mostly around the belief that capitalism is a doomed economic system and the view that global warming and other ecological problems are reaching tipping points.

As committed progressives, Lilley and Yuen share these basic beliefs. “Capitalism is an insane system,” Lilley said, while Yuen said climate change and loss of biodiversity really are catastrophes: “We are living in an absolutely catastrophic moment in the history of the planet.”

Yet they also think it’s a fallacy to assume capitalism will collapse under its own weight or that people will suddenly — on Dec. 21 or at any other single moment — decide to support drastic reductions in our carbon emissions. These changes require the long, difficult work of political organizing — which has been underway for a long time — whereas Lilley called catastrophism “the result of political despair and lack of faith in our ability to take mass radical action.”

It’s tempting to believe that capitalism is one crisis away from collapse, or that people will be ripe for revolution as economic conditions inevitably get worse, but Lilley said that history proves otherwise. “Capitalism renews itself through crisis,” she said, whether it was the collapse of the banking system in 2008 or weathering the anti-globalization and Occupy Wall Street protests.

Sounding the alarm that capitalism and climate change will devastate communities doesn’t motivate people to action.

“It focuses on fear as a motivating force, but I think it really backfires on the left,” Lilley said. “It’s really immobilizes people…It’s paralyzing and deeply problematic.”

In fact, she said, “It’s important that we don’t succumb to what’s been called the left’s Rapture.”

DEATH AND REBIRTH

So what if the sky doesn’t fall Dec. 21 — and solutions don’t fall from the sky either? Are we are just going to die?

Yes, we are, at least in old forms, a process that can be cause for celebration and empowerment.

“Really, what’s happening is a psychological death, an identity death of what it means to be human on the planet,” Marshalla said.

He compared it to the five stages of grief identified by author Elizabeth Kubler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and then finally acceptance. Marshalla thinks humans are in the depression stage, verging on accepting that our old way of life is dying.

Part of that acceptance involves embracing new self-conceptions. When humans developed the prefrontal lobe in our brains, it allowed us to not only climb to the top of the food chain, but to achieve unprecedented control over the natural world.

But at this point, we’ve become too smart for our good, rationalizing behavior that our heart knows is out of balance, causing us to forget essential truths that we once knew, such as our power to create our reality and the humility to live in harmony with the natural world.

We learn apathy and competitiveness the same way we can learn empowerment and cooperation. “The goal is to bring on that peaceful, loving state of mind where we see all of us as equal,” Marshalla said, noting that it doesn’t really matter whether that’s achieved through traditional religion, meditation, political organizing, or belief in ancient prophecies and energies showering down from the galactic center.

“It’s less about being right than finding any way to lift us up, so whatever thoughts take us there,” he said. “It’s whatever causes us to realize that shift is upon us.”

Whether the universe and mythology have anything to do with it, the hold they have on human imagination, belief, and intention is still a powerful force — and maybe it can create self-fulfilling prophecies that a new age of global consciousness and cooperation is dawning.

“That’s the best thing the Dec. 21 date can be, a ritual of acknowledging that we’re in the midst of a fundamental transformation,” Brezsny said. “The activists believe this may be a good moment, a good excuse to have a transformative ritual and to take advantage of that. We need transformative rituals.”

The ancient Mayans and the energies of the galactic center may not deliver the solutions we need, although I’m certainly willing to wait a few days — or even a few years — to receive this moment with an open heart and open mind. Why not? Let’s all bring our own visions and prophets, mix them into the cauldron, and watch what bubbles up.