EDITOR’S NOTE:

As we move through tumultuous times in San Francisco and start a year with infinite political potential, we decided to stretch our imaginations a bit. While this is clearly a work of satire that appropriates some local media voices and perspectives, we hope that even its most fantastical moments will give this parable some resonance with our readers. Happy new year!

EDITORIAL The most exciting and promising political development we’ve seen in a long time in San Francisco is the sudden emergence of so-called Candidate X, who has quickly parlayed groundbreaking populist efforts to reform Muni and housing development into a full-blown campaign for mayor.

While the election is still 22 months away — an eternity in electoral politics — we’re going to go out on a limb here and offer the Candidate X campaign our early endorsement. Political movements like this one are once in a generation opportunities, and it will only be successful with strong, early support.

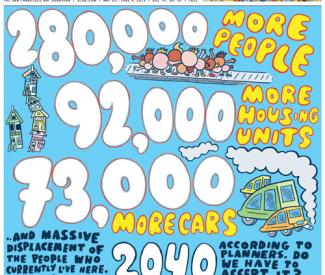

There’s just too much at stake for politics as usual, or to trust Mayor Ed Lee’s sudden recognition that his economic development policies and deference to market-rate housing developers were hurting San Francisco’s vitality and diversity and igniting a popular uprising, which Candidate X suddenly emerged to help lead.

In case you’ve been living in a cave for the last month, 2014 began with an explosion of progressive activism that finally began to bridge the gap between longtime San Francisco communities and a group of fairly apolitical but Internet-savvy new arrivals, many of whom work in the technology industry, which had been increasingly vilified as elitist and out-of-touch with the city’s values and history.

A mysterious, masked figure calling himself or herself (nobody is quite sure) Candidate X used social media on New Year’s Day to announce bold plans to “disrupt the streets of San Francisco,” calling for vaguely defined meet-ups at a dozen key spots around the city on the morning of Jan. 3.

A mysterious, masked figure calling himself or herself (nobody is quite sure) Candidate X used social media on New Year’s Day to announce bold plans to “disrupt the streets of San Francisco,” calling for vaguely defined meet-ups at a dozen key spots around the city on the morning of Jan. 3.

The multi-pronged response was overwhelming and surprisingly coordinated, perhaps an indicator of offline organizing that exceeded the viral online phenomenon. Google and other corporate buses were commandeered into free public service (with the collusion of many drivers and regular riders) while Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and other online funding drives raised at least $10 million for Muni to expand its service, a potent mix of fiscal and people power. And that epic day ended with an unpermitted rally of at least 10,000 people in Civic Center Plaza.

A week later, Candidate X followed up with a similar effort to jumpstart affordable housing construction in the city, using a combination of carrot and stick (humanist appeals to project backers and direct action at construction sites) to persuade a half-dozen market rate developments to substantially increase their affordable housing mix. And the candidate helped organize a mass mobilization that brought thousands of tenants to City Hall — and generated 10 times as many emails and calls — to force the supervisors to support a measure raising the relocation fees on Ellis Act evictions so high that the speculators were almost instantly driven out of the city.

Candidate X is now talking about raising even more money for Muni by quadrupling the mitigation fees developers pay to construct new offices.

Those campaigns were coupled with hundreds of activists using hoes, picks, and shovels on public land that was part of the 8 Washington luxury condo proposal, removing the parking lots and grading the land by hand for a communal housing project they intend to build on the site.

The next week, with the Candidate X movement gaining momentum at astonishing speed, Candidate X announced his/her intention to run for mayor in the November 2015 election, starting now. The campaign has already announced a series of radical but smart positions, from banning cars on Market and other key streets to reclaiming Treasure Island and Hunters Point Shipyard from Lennar’s control, and promising many more to come.

In some ways, it seems like a marriage between the surging housing rights movement — which has been challenging evictions and gentrification and fighting for the soul of San Francisco — and the social media-driven Batkid outpouring back in November. But rather than an apolitical one-off, this feels like a broad movement focused on shaping San Francisco in the public interest over the long term.

The whirlwind of exciting political energy has left many speechless, and we can only say: Candidate X for mayor!

While the Candidate X phenomenon has certainly captivated San Franciscans and attracted national media attention, giving the city’s far-left progressives a glimmer of hope in capturing the Mayor’s Office next year, those close to Mayor Ed Lee say they aren’t worried.

While the Candidate X phenomenon has certainly captivated San Franciscans and attracted national media attention, giving the city’s far-left progressives a glimmer of hope in capturing the Mayor’s Office next year, those close to Mayor Ed Lee say they aren’t worried.

“Everybody’s having fun with this now, but at the end of the day, voters are going to prefer a proven leader like Mayor Lee and his successful jobs agenda to some kind of strange masked comic book character,” a source in the Mayor’s Office told us. “Whatever this thing is, it’ll be a footnote in the mayor’s race.”

The source cited internal polling indicating the Mayor Lee’s approval rating holding steady at more than 70 percent and unaffected by the last three months’ worth of headline-grabbing antics by Candidate X and his or her campaign. The polls also found the public is turned off by the candidate’s mask and secret identity.

The source cited internal polling indicating the Mayor Lee’s approval rating holding steady at more than 70 percent and unaffected by the last three months’ worth of headline-grabbing antics by Candidate X and his or her campaign. The polls also found the public is turned off by the candidate’s mask and secret identity.

Candidate X has certainly proven adept at using social media and other technological tools to generate support, but Angel investor Ron Conway and his sf.citi collaboration of technology industry leaders have pledged to help make tech-driven outreach and voter identification a centerpiece of Lee’s reelection campaign.

“Entrepreneurs have made this city what it is, and we’re not going to let this Candidate X creature undermine our agenda for San Francisco,” Conway said. “Let them have their fun for now, we’re not worried.”

Sometimes, revealing the fakers in politics can be easy.

Sometimes, revealing the fakers in politics can be easy.

And so it goes with the so-called “Candidate X.” The self-stylized Progressive Hero is a multi-racial, gender ambiguous second coming of Christ for the city’s super-lefties. The narrative began with a PR move that undoubtedly had Willie Brown weeping into his Wilkes Bashford handkerchief.

Brown promised to fix Muni in 100 days, and Candidate X fixed it with one glorifyingly stupid stunt.

Masked and spandex clad, Candidate X straddled two Muni buses while doing the splits, Van Damme style, between them. X rode the buses spread eagle, laughing like a demented Santa Claus, as streams of San Franciscans ran behind them down Geary Boulevard. Using the ploy to call for Kickstarter of America’s Worst Transit System, millions of streaming video gawkers nationwide flocked to and knocked out the crowd funder’s website.

The silliness ended before you could say “back door!”

It was seemingly successful. Defying the history of failed fixes from every ex-San Francisco mayor since forever, X single-handedly raised enough money to “expand Muni for the next three decades,” progressives claimed.

Some played it as a progressive spurning of Mayor Ed Lee’s proven political tactic — ignore Muni’s issues and glorify the Google buses. Some portrayed it as a socialist takeover of an already red or dead leaning City by the Bay. Your humble narrator knew better.

X is a ludicrous candidate no sane citizen would back, and that stunt was clearly that — a stunt. But still the quixotic charade marched on.

X is a ludicrous candidate no sane citizen would back, and that stunt was clearly that — a stunt. But still the quixotic charade marched on.

Last week, X sat Mark Zuckerberg and a team of star studded tech oligarchy down with progressive activists. The previously evicted Lee family was there, arm-in-arm with former Mayor Art Agnos and a cadre of lefty power in San Francisco, or what’s left of them anyway. With Candidate X in the center of the two contentious camps, the tableau was vaguely reminiscent of the Last Supper, save for the presence of Mission District burritos.

San Francisco’s problems were tastily tackled one by one.

Housing problems? Hacked and solved. The homeless? Software solutions streamlined shelters in a day. Even hunger among the city’s poor was licked, as the techies and lefties together crafted solutions mind-melding the best ideals of both. All throughout, a time bomb ticked away like a demented clock ready to strike “I told you so!” at midnight.

It’s difficult to watch impending doom stare well-meaning people in the face. Literally staring, as the problem came the person posing for all the cameras: Candidate X.

Last week the candidate’s violent history was revealed, and although the SF Weekly doesn’t have a stock of X-ray glasses, your humble narrator still saw this coming a long way back. X is a fraud. A charlatan. A wannabe in progressive clothing. And now we all know why.

In police records obtained by the City Attorney’s Office, Candidate X was revealed to be one of the Occupy San Francisco and Oakland protesters, maybe even from the pernicious Black Bloc. Way back when, the Bay Area was captivated by martyred rallier Scott Olsen and others who were wronged by the not-so-mighty Oakland Police Department. OPD tear gassed and grenaded the Occupy pests. At the same time, a more intimate, frightening drama played out across the bay in San Francisco’s Embarcadero.

The SFPD was mostly kind to their own Occupy camp, but one boy in blue was not: Officer Alex Murphy. He paid dearly for it. One night, sleeping in his tent at the Occupy camp, Candidate X was roused by Murphy and ushered to leave. Does that translate into the officer deserving a beating within an inch of his life? It seems Candidate X thought so, although he also seems to have got as good as he gave, and ended up in the hospital.

The Black Bloc folks aggressive ways led the public to link Occupy with violence, from hippies to rage rousers. Black Bloc and Candidate X were kindred souls. Even his heart was black.

X yanked Murphy behind the fountain at Justin Herman Plaza, and punched him repeatedly, savagely, in the face, Murphy said in police reports, eventually pinning the officer to the ground before he got his.

Candidate X put up the usual defenses. “Murphy was near murderous with protesters all night, he’d gone vigilante,” Candidate X told scads of TV crews in Aaron Sorkin-esque walk and talks, last week. Protesters said he saved their lives, hailing his heroism. San Francisco shouldn’t buy the story. It’s malarkey, plain and simple.

But good reasons or no, is a violent wacko the kind of candidate you want leading the new progressive movement? Not surprisingly, it seems the new progressive era is like the old one. Big dreams, empty promises, and a lot of rhetoric that will soar nowhere.

And no one, especially not your humble narrator, was surprised.

The electoral landscape today is much different than it was only last week, when the revelation of Candidate X’s brawl with police had pulled the mayoral hopeful’s poll numbers into the ground.

The electoral landscape today is much different than it was only last week, when the revelation of Candidate X’s brawl with police had pulled the mayoral hopeful’s poll numbers into the ground.

Now a new viral video released by members of the San Francisco Occupy camp from 2011 confirms X’s side of the story: Officer Alex Murphy broke ranks with the generally peaceful SFPD. Police Chief Greg Suhr had a mostly “hands off” policy, allowing the Occupiers their right to free speech.

Murphy did not follow those directives, however, and the video shows the officer swinging his baton wildly, throwing punches, and injuring several protesters in the night, only to be fought off by Candidate X.

The story of X’s fight with an SFPD officer during the Occupy encampments had many saying the candidate’s campaign was over.

“That’s not someone I’d trust to be the leader of San Francisco,” said Mayor Ed Lee Press Secretary Christine Falvey.

The release of the video casted doubt on Murphy’s side of the story, and changed the electoral climate in the city going into next month’s election, when five seats on the Board of Supervisors are on the ballot.

Progressives in San Francisco scored big victories in last night’s election, winning seats on the Board of the Supervisors that a year ago seemed secure for the incumbents, thanks largely to a populist surge triggered by the mysterious Candidate X mayoral campaign.

Progressives in San Francisco scored big victories in last night’s election, winning seats on the Board of the Supervisors that a year ago seemed secure for the incumbents, thanks largely to a populist surge triggered by the mysterious Candidate X mayoral campaign.

Although neither Mayor Ed Lee nor Candidate X will appear on the ballot until next year, this year’s legislative races clearly got caught up in the enthusiasm of that race, with David Campos defeating David Chiu in their Assembly race and three members of the Board of Supervisors replaced by progressives.

Attorney David Waggoner took Sup. Scott Wiener’s District 8 seat and previous political unknowns Jennifer Wong and Betty Jones scored improbable victories in the Districts 2 and 10, defeating Mark Farrell and Malia Cohen.

District 6 incumbent Jane Kim appears to have narrowly won reelection after being strongly challenged by three candidates to her left, who criticized her ties to Mayor Lee and her sponsorship of the big tax break for Twitter and other mid-Market businesses almost four years ago. But Kim appeared to blunt that criticism by leading this year’s repeal on that and other business tax breaks and firmly aligning herself with Candidate X.

Kim’s vote in favor of raising fees on Ellis Act evictions and more than tripling the fees charged to office developers for Muni and affordable housing almost certainly saved her seat — and the refusal of Farrell and Cohn to support the tenant and economic fairness agenda were major factors in the campaigns that unseated them.

Candidate X defies easy categorization, and confusion surrounding this political dynamo’s gender identity is just the tip of the iceberg.

Candidate X defies easy categorization, and confusion surrounding this political dynamo’s gender identity is just the tip of the iceberg.

Since announcing her candidacy, she’s been the subject of rampant speculation among the city’s political insiders. Is she a native Spanish speaker, or did she grow up speaking Cantonese? Was she born and raised in San Francisco, or is she a transplant from the Midwest, or a foreign-born resident? Which supervisorial district does she live in? What is her annual income? Does Candidate X have any tattoos?

For all the questions this rollercoaster-like campaign has raised, Candidate X has left little doubt about his stance on certain issues. He frequently spouts a philosophy of “radical inclusion,” which he says could be put into practice in San Francisco city government by creating an online platform where all residents could log in and vote directly on discretionary funding allocation. He’s proposed eliminating the system of mayoral commission appointments altogether, instead allowing residents to digitally cast votes for commissioners. And he’s floated the idea of making every single public document tagged, searchable, and readily available, to anyone, the moment it’s created.

Candidate X’s unique method of campaign fundraising has spurred several economic studies. She’s created partnerships with a wide network of independently owned, San Francisco small businesses to allow customers to chip in a bit extra when they make a purchase, then used her considerable social media reach to encourage supporters to shop at those businesses. The approach has helped her tap a broad pool of donors, while sending new clientele through the doors of struggling proprietors in every corner of the city, many of whom have been losing ground in the face of rising rents and competition from national chain stores.

Candidate X has also organized campaign fundraising events with sliding scale admission fees. They are rumored to draw large, diverse crowds and occasionally last until sunrise, with attendees lingering for impassioned political discussion long after the performers have left. The events tend to start early in the evening with talks by local artists and authors, followed by aerial circus arts performances and live sets by Bay Area bands spanning a wide range of musical genres.

Candidate X has met with experts on climate change and used their input to produce a comprehensive plan for developing city-owned renewable energy infrastructure, which she says could be staffed with graduates of a job-training program created for at-risk youth. She’s also undertaken a project of identifying every abandoned property in the city that could be converted to residential use, as part of a plan to open up new transitional housing for homeless residents, to be staffed with a veritable army of substance abuse counselors and mental health professionals.

Earlier this month, when baristas organized a citywide protest against gentrification — by withholding coffee and shutting down Wi-Fi networks — Candidate X rode his bike from café to café to stand with the aproned employees while bleary-eyed patrons lined up outside the doors in confusion, clutching their laptops.

“Today, you are going to have to make your own coffee and work from home,” Candidate X told the bewildered patrons, after baristas shared personal stories of facing eviction or anxiety over losing rental housing.

“These baristas have taken a courageous stand for economic justice, to defend San Francisco against real estate speculators and developers who hold no regard for this city’s long tradition of inclusion and equality. They will not make your Ethiopian pour-over coffee with complex flavors of lilac and lavender while you connect to their free Wi-Fi — until you join in the fight against real-estate speculators whose actions have threatened this city as a haven for people of all incomes and identities.”

Since then, rumors have surfaced that someone in the tech community who heard the baristas’ stories that day has since started collaborating with the San Francisco Tenants Union, to create an app to help apartment-hunting tech workers boycott landlords who are known to carry out evictions and harassment — and to track evictions and alert house-hunters to join in refusing to bid on properties emptied by eviction.

So it seems that Candidate X has done the unthinkable, and gotten the younger voters of San Francisco to actually give a damn.

So it seems that Candidate X has done the unthinkable, and gotten the younger voters of San Francisco to actually give a damn.

In his (her? their?) latest headline-grabbing move, Candidate X registered nearly 100 percent of voters age 18-30 in San Francisco just in time for the next election.

How’d X do it? The SF Examiner explains:

“In what could become a regular afternoon ritual, Candidate X stopped by college campuses, hip coffee shops, and Dolores Park this week with representatives of the tech industry and every San Francisco constituent group in tow.

The elderly, the homeless, new immigrants and others volunteered their time to convince every young voter, one by one, why it was worth their time to register to vote.

“I’ve never felt like I had a reason to give a damn, really,” said Martin Collins, 22. “Maybe it was X’s energy, which felt like (President) Obama’s campaign… or maybe it was because Macklemore was there. Either way, I’m voting next election.”

There you have it folks. X is so revolutionary. All you have to do is bring famous people to your voting drive, or you know, tout “hope and change.”

That always works. Last time Ed Lee ran for mayor, only around 30 percent of San Franciscans turned out to vote. Now Lee really has something to worry about.

Candidate X has been an enigma from the beginning, a vessel of progressive hopes for finally winning the Mayor’s Office. And at tonight’s triumphant election night party, we learned that we’re all Candidate X.

Candidate X has been an enigma from the beginning, a vessel of progressive hopes for finally winning the Mayor’s Office. And at tonight’s triumphant election night party, we learned that we’re all Candidate X.

As exciting as the political victory was the hope that the masked Candidate X would reveal her or his identity after winning the race, which the current 15-point margin all but assures. That made for a big moment when Candidate X came onstage in Bill Graham Civic Auditorium to address the large crowd.

“This election was a fight for the soul of San Francisco and beyond. It was a referendum on the belief that we should leave this great city and others like it to the mercies of market forces, and the people have now said they want to be in control. Politicians often claim their victories are really victories for the people, but tonight, that’s finally true,” Candidate X said.

At that moment, dozens of nearly identical Candidate Xs — with the ubiquitous mask, cape, and costume, that image that has so captivated the country over these last 22 months — streamed out from backstage and filled the stage.

“1, 2, 3,” they all said in unison, all of them pulling off their masks at the same moment, revealing themselves to be a broad cross-section of city residents: young and old, men and women, attractive and plain, black and white and every shade in between.

“You see,” said the Candidate X who had originally come to the microphone, who appeared to be an Asian woman around 40 years old. “From the very beginning of this campaign, there’s never been a single Candidate X. We’ve all worn the mask at different times, we’ve all stood on the stump to proclaim the progressive values that this election was about, and we’ve all run this race.”

“Some of us have been doing this for a long time,” said a costume-clad Tom Ammiano, the longtime local legislator who last ran for mayor in 1999, “and we knew this moment needed to be about more than just one leader. So we created a vehicle that we could all ride into Room 200.”

Ammiano told the Guardian that he had been part of the large team that conceived of Candidate X during a series of secret meetings in late 2013. He said the campaign hopes and believes that its entire X Factor Leadership Team will be allowed to legally govern the city, but that just in case the Lee team challenges the unconventional arrangement in court, Ammiano last year legally changed his name to Candidate X and that he will serve as the figurehead for that governing structure if necessary.

“To turn this city around and restore it as an example for the world is a job for all of us, not any one person or faction,” said another Candidate X, who appeared to be African American woman in her early 20s. “We face challenges ranging from unaffordable rents here to global warming and loss of biodiversity everywhere. And it’s going to take all of us, working and standing together, to solve these problems and create a just and inclusive society, today and for future generations.”

“Todos somos Candidate X,” declared an elderly Latino Candidate X. “We are all Candidate X.”

*All new items written by Steven T. Jones, Rebecca Bowe, and Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez

One-time fares may jump to $2.25. Muni’s monthly passes would see an increase by $2 next year and more the following year. The “M” monthly pass will be $70 and the “A” pass (which allows Muni riders to ride BART inside San Francisco) will be $81.

One-time fares may jump to $2.25. Muni’s monthly passes would see an increase by $2 next year and more the following year. The “M” monthly pass will be $70 and the “A” pass (which allows Muni riders to ride BART inside San Francisco) will be $81.

A mysterious, masked figure calling himself or herself (nobody is quite sure) Candidate X used social media on New Year’s Day to announce bold plans to “disrupt the streets of San Francisco,” calling for vaguely defined meet-ups at a dozen key spots around the city on the morning of Jan. 3.

A mysterious, masked figure calling himself or herself (nobody is quite sure) Candidate X used social media on New Year’s Day to announce bold plans to “disrupt the streets of San Francisco,” calling for vaguely defined meet-ups at a dozen key spots around the city on the morning of Jan. 3.

The source cited internal polling indicating the Mayor Lee’s approval rating holding steady at more than 70 percent and unaffected by the last three months’ worth of headline-grabbing antics by Candidate X and his or her campaign. The polls also found the public is turned off by the candidate’s mask and secret identity.

The source cited internal polling indicating the Mayor Lee’s approval rating holding steady at more than 70 percent and unaffected by the last three months’ worth of headline-grabbing antics by Candidate X and his or her campaign. The polls also found the public is turned off by the candidate’s mask and secret identity.