arts@sfbg.com

FILM It’s a bit difficult from hereabouts to get a hold on what kind of star Paprika Steen is in Denmark, beyond being a kinda huge one. Here, she’s at most a familiar face from the Dogme 95 movies of a decade or more ago, having appeared in such significant entries as Thomas Vinterberg’s The Celebration (1998), Lars von Trier’s The Idiots (1998), and Susanne Bier’s Open Hearts (2002), as well as subsequent non-Dogme films by those and other leading directors. From those you might figure she’s a leading light in a sort of loose stock company of people who constantly work in each others’ emotionally unruly, sometimes outrageous, usually satisfying movies.

But at home it seems she’s more ubiquitous, in various media and as an all around personality. There they’ve gotten to see her in films we haven’t (particularly envied is 2007’s The Substitute, in which she plays a space monster posing as the world’s worst elementary school teacher), in TV series, as a skit comic, stage actress, and god knows what else — there’s a mystifying YouTube clip of her gyrating through a “Single Ladies” cover on some awards show, and it does not appear intended as a joke.

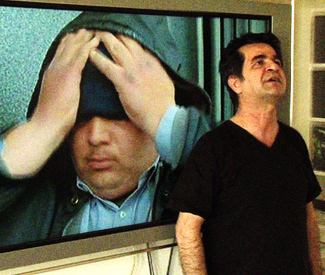

The new-ish (it’s taken its sweet time crossing the Atlantic) Applause distills what we might already know and guess at about this skillful, somewhat larger-than-life actress. She plays Thea Barfoed, a duly larger than-life actress undeniably skillful at her job — a flunky gushes she’s “one of the best in the whole country,” causing Thea to bristle not just at “one of,” but at the dinkiness of said country — but a floundering mess everywhere else.

We first see her playing Martha, natch, in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? onstage (sequences shot during a real-life production of the Albee play Steen starred in), boozing and yelling, reeling and lashing about. It’s typecasting: offstage, Thea is just out of rehab, having hit a bottom that ended her marriage and handed her husband (Michael Falch) sole child custody. Yet she’s still sneaking booze, even during performances; attending AA meetings she yawns and smokes through while others bare their souls. Snapping “I hate ordinary people” — no one is convinced when she claims that was a joke — she has that unpleasant brat-egomaniac’s manner of suggesting everyone else is wasting her time with their stupidity, and that any attempts to be civil on her part require a Herculean exercise in acting. It’s hard to pity her evident self-loathing when she’s such a complete asshole.

Still, she wants to be better, sort of, and others are trying to help. Ex spouse Michael and his infuriatingly reasonable new partner (Sara-Marie Maltha) have decided it’s best for all that she have visitation rights to her young sons, despite the past (which included unspecified maternal physical violence). When Thea sees the boys for the first time in 18 months, they’re understandably skittish. Struck by their fearful distance, she goes home and pours every intoxicant down the drain. But she still has the overpowering and impulsive needs of an addict — whether exercised in her way-too-soon demands for custody, a weird and unwise bar pickup (Shanti Roney), or the rant directed at a dim Toys R Us salesgirl who momentarily gets between Thea and the impossible dangling carrot of happiness.

Rather incongruously nostalgic in its Dogme-style aesthetic of shaky camera and jump cuts (editor-turned-director Martin Zandvliet has since made a much more classically polished second feature), Applause is a good movie that’s unimaginable without Steen. Yet it might have been better still if less overwhelmed by her. Like a salad plate supporting an entire roast turkey, its narrative framework is underscaled for such a glistening mass of banquet-sized acting meat.

With her great mane of hair looking magnificent one minute and Medusa-like the next, she’s a glam gorgon, both utterly credible and nearly Joan Crawford-esque in determination to stare the medium down. Paprika Steen is the kind of actress who revels in making herself unattractive, though the ravaged result is less “plain” than its own kind of masochistic spectacle. (Thea is the very picture of a proud 25-year-old beauty two decades and umpteen cosmos later.) It’s a flamboyant, arresting, faultless star turn — even if Applause itself is finally just a vehicle. To really gauge what she’s capable of, we’d probably need to see that Virginia Woolf? in its entirety.

APPLAUSE opens Fri/13 in Bay Area theaters.