Years ago, the San Francisco Chronicle handed Willie Brown a megaphone, but now that he’s officially recognized as a paid lobbyist, isn’t it time to yank it back?

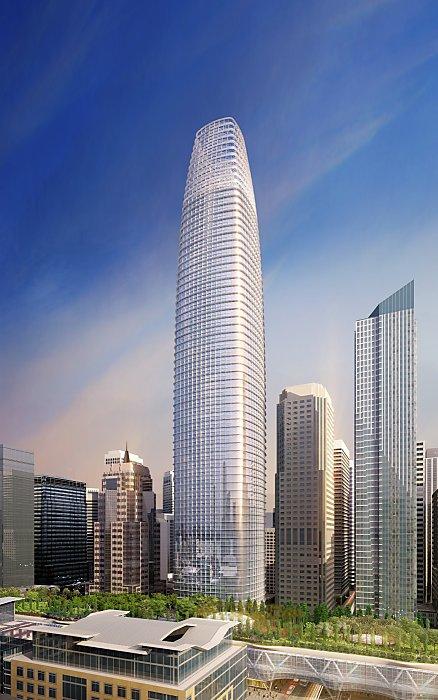

Weekly Chronicle columnist and former Mayor Brown’s newest Ethics Commission filings show he’s been paid $125,000 to lobby the city on behalf of Boston Properties, negotiating for the developers who are threatening to sue the city over a tax deal worth up to $1.4 billion to San Francisco. Boston Properties were told going into the deal they’d pay taxes based on property values in the South of Market district, where the high-rise Salesforce Tower (formerly the Transbay Tower) and other developments will soon be built.

The loss of funding in the special tax zone known as a Mello-Roos District (which, in a twist of another sort, was created when Brown presided over the California Assembly) could jeopardize the high-speed rail extension from the Caltrain station at 4th and King streets to the new Transbay Terminal, possibly downgrading it into a very expensive bus station. We left an interview request with Brown’s assistant for this piece, but received no reply.

Brown has long sold his influence to the highest bidders, although he claimed to be their lawyer and not their lobbyist, but now Brown is legally out in the open as an advocate against the city’s interests. He’s now officially a registered lobbyist (finally).

But the Chronicle still publishes Brown’s column, Willie’s World, giving “Da Mayor” a weekly space in its prominent Sunday edition to charmingly joke away his misdeeds (which raised the eyebrows of the Columbia Journalism Review for its maddeningly obvious ethical concerns). In his newest column, Brown kiddingly brags about taking bribes:

“John Madden got off a great line the other night when we were sitting in the St. Regis lobby.

I was reading off my itinerary for the evening when he stopped me, turned to another guy and said, pointing my way, ‘He’s the kind of politician who goes everywhere. As a matter of fact, he’ll show up for the opening [sic] an envelope.’

It all depends on what’s in it.”

In his column the week before, he trumpeted a potential political ally while taking pot-shots at high speed rail, the very same project that Boston Properties seeks to defund by depriving the city of tax dollars for the Salesforce Tower project:

“There is a very impressive star on the horizon. Her name is Ashley Swearengin. She is the mayor of Fresno, and she’s running for controller against Democrat Betty Yee.

She is also a Republican who is being pilloried by other Republicans for her support of Gov. Jerry Brown’s high-speed rail project. Unlike some politicians, Swearengin has a concrete reason for backing what some are calling the ‘train to nowhere.’ It means a ton of construction jobs for Fresno.

Supporting high-speed rail, however, has cost her in the fundraising department because many potential Republican donors hate the project.”

And maybe because he’s digitally disinclined to use Twitter, in July he used the Chronicle as his own personal communications service to contact federally indicted and alleged-gun-running Sen. Leland Yee:

“Where’s Leland Yee? I’ve got everybody in town looking for our indicted and suspended state senator, and no one can find him. Leland, if you read this, call me.”

We reached out to Chronicle Managing Editor Audrey Cooper to ask her if San Francisco’s paper of record would consider retiring Brown’s column now that he’s a registered lobbyist, but didn’t hear back from her before we published. But you know, they could always go the other way: Why stop with Willie? Just give up guys, and give editorial space to BMWL (who are pushing against the Soda Tax), to Sam Singer (the high-powered public relations flak), or Grover Norquist (he could write about the virtues of libertarianism and Burning Man at once!).

But Brown is a special case all on his own. He’s no ordinary lobbyist: He has the ear of the mayor (and helped elect the mayor), and his influence cuts a swath through the city’s biggest power players, from PG&E to Lennar Corporation. He helped many current city politicians and staffers get their jobs in the first place.

The average reader not steeped in wonky political backdoor deals may not understand why giving him a column is such a bad idea. Journalist Matt Smith has long-written on Brown’s SF Chronicle conflict of interest, first for the SF Weekly and then for the now-defunct Bay Citizen. In 2011, an anonymous Chronicle staffer told this to Smith:

“‘Should the newspaper be in the business of helping an influence peddler peddle?’ the journalist asked.

‘If you believe him even 50 percent of the way, Willie Brown has a big say in San Francisco politics, which he reminds us of every week. He has a certain self-deprecating style that makes him even more charming, which kind of hides the fact that what he is really doing is bragging about all the people he knows, and all the influence he peddles. What that does is it has a multiplier effect.'”

That multiplier effect works in a few ways. First, it works almost as information-laundering: When Brown “jokes” about taking bribes, it makes any accusations of impropriety seem quaint. After all, it’s just Willie Brown, we already know he’s a wheeler-and-dealer, right? What harm could he do?

Second, it amplifies his already formidable position as a kingmaker in San Francisco politics, possibly allowing him to charge even more cash to special interests for his influence. Since he registered as a lobbyist, Brown has met five times with Mayor Ed Lee over the Salesforce Tower tax issue. And until the Chronicle’s surprising and incredibly rare editorial stance against Mayor Ed Lee’s deal, Brown almost succeeded in negotiating hundreds of millions of dollars out of city coffers and into the pockets of Boston Properties.

The Chronicle wrote scathingly in their editorial:

“The deal is baffling — and infuriating. The group of developers had already gotten special favors from City Hall.”

Swap the words “the group of developers” with “Willie Brown,” and you could say the exact same thing about Brown’s Chronicle column.

Brown even used his San Francisco Chronicle headshot in his lobbyist registration with the Ethics Commission. If that’s not a “fuck you” to the Chronicle’s sense of journalistic ethics, I don’t know what would be. The Chronicle’s photo editor told us in an email that Brown did not have permission to use the photo.

I don’t think he cares.