joe@sfbg.com

San Francisco’s overheating housing market has polarized the city. While progressive activists push to protect rent-controlled apartments and encourage construction of new below-market-rate housing, moderates, Realtors, and developers say any new housing helps keep prices in check, calling on the city to build 5,000 units per year.

But there is a hidden side to the housing issue in San Francisco, one that offers both complex challenges and enormous potential as a source of housing for low-income city residents, and it’s getting a fresh look with desperate eyes.

Secondary units — also known as granny flats or in-law housing — dot the city by the thousands, and are for the most part illegal. They’re tucked behind garages, in basements, or in backyards, most of them single serving sized and largely ignored.

Such units are legal under California law, and the reasons they’re quasi-legal in San Francisco are complex. It mostly boils down to the fact that often these units aren’t up to Building or Planning codes, but there have also been decisions to deliberately limit density in some neighborhoods, sometimes driven by concerns about more competition for street parking spaces.

Tenants in such units can be reluctant to report housing code violations for fear of losing cheap apartments in this rapidly gentrifying city, even if that means living in substandard housing. And the owners of those units often can’t afford to bring them up to code or pay the fines. It remains an underground industry with few watchdogs.

Caught between conflicting realities of housing shortages, poverty, and safety, the city has largely turned a blind eye to in-law units, adopting what housing advocates call a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy around inspecting in-law units. Now that may change.

Board of Supervisors President David Chiu and Sup. Scott Wiener have plans in the works that could spur development of secondary units in the city. San Francisco has been there and done that though, and the bodies of failed past granny flat campaigns litter the political wasteland.

“In-law legalization has been for a lot of housing advocates the holy grail, but for a lot of politicians, it’s been a third rail,” said Tom Radulovich, executive director of Livable City, a nonprofit group that advocates for a more walkable, livable San Francisco.

Despite the many failed jump starts over the years, Radulovich sees hope in the prospects of legalizing more secondary units because “it’s a good, cheap, and green way to add housing.”

BUILD SMALL

So what’s different now? First off, unlike past efforts, the politicians involved are taking some small but significant steps.

Wiener’s plan could directly spur the creation of new secondary units, but it’s limited to only the Castro District. It basically lifts caps on the number of units that can be built in a single residence, waiving some density and other Planning Code requirements.

Wiener views his plan as a pilot program. “I decided to try a more limited geographic area to show that it can work,” he told us, saying that the past failed campaigns tried to force the issue citywide.

The Castro is a prime candidate for more affordable housing. The neighborhood has many tenants who are single, Wiener said. And as gentrification slammed the Castro, the vulnerable were hurt as well. Jeremy Mykaels, a 17-year Castro tenant living with AIDS, recently fought back an Ellis Act eviction that would have cost him his home.

“I am not looking for pity,” Mykaels wrote on his website, addressing his eviction. “I just want to shed a light on a growing problem in this city for many senior and disabled tenants like myself.”

Wiener’s office declined to say how many secondary units could be built. But as he introduced the legislation to the Board of Supervisors on Oct. 22, he said that many longtime residents in the Castro, in terms of housing, “are living on the edge.”

Castro residents like Mykaels have lived under rent control for years, and once folks like him are pushed out, they often can’t afford to stay in the city.

Fair market rent in the Castro for a two-bedroom apartment is $3,295 a month, according to the Department of Public Health. According to its rental affordability map, a tenant would need 6.2 full-time minimum wage jobs to afford to live there.

“It’s a neighborhood in desperate need of additional housing options,” Wiener said.

Enter in-law units, which are often more affordable. Though there have been no citywide studies of their affordability, a study this year by the Asian Law Caucus, “Our Hidden Communities,” said the average cost of those units in the Excelsior neighborhood is between $1,000–$1,249 a month, way below average rents.

Wiener’s legislation was turned over to the Land Use and Economic Development Committee, where it will be evaluated for impacts to the neighborhood. The supervisors will hear it again in 30 days.

GO BIG

One housing advocate thinks Wiener is thinking too small and needs to expand his vision.

“I think Wiener’s proposal is creating a patchwork of regulation, but this will create a mess, which the board is accomplished at doing,” Saul Bloom, head of Arc Ecology, told the Guardian. He thinks a citywide proposal to legalize in-law units is the only way go to — because the city is in a housing crisis right now, he said, and we don’t have time for just a pilot.

One big advantage is the units are far cheaper to construct than traditional houses or condominiums. Bloom notes the Lennar Urban will be spending about $400,000 for each of the thousands of homes it will build at Hunters Point Shipyard and surrounding areas, but that small secondary units can be built in existing neighborhoods for $75,000 to $200,000 each.

“We’re not expanding units in affordable housing through existing strategies,” Bloom said, and he’s right.

San Francisco has mostly built about 1,500 new housing units a year, which is much less than needed to keep up with demand, according to San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) and the Housing Action Coalition.

To keep up with the frantic demand, San Francisco would need to build 5,000 new units a year, the groups argue. If the city could keep up with demand for housing, the price of housing itself could go down — meaning lower rents for everyone.

“If we want to actually make the city affordable for most people — a place where a young person or an immigrant can move to pursue their dreams, a place a parent can raise kids and not have to spend every minute at work — we have to fix the supply problem,” SPUR Executive Director Gabriel Metcalf wrote in a recent article for The Atlantic (“The San Francisco Exodus,” Oct. 14).

Yet progressive housing activists have long said that the city can’t build its way to affordability, arguing that demand for market rate units is essentially insatiable, and that what the city needs to do is build housing specifically for low-income residents.

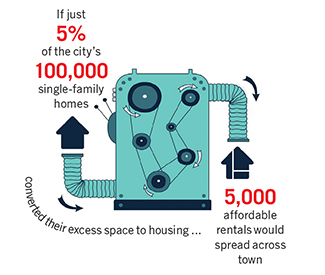

Bloom put out a study from Arc Ecology, suggesting that if just 5 percent of the city’s 100,000 single family homes converted their excess space into in-law units, an additional 5,000 affordable rentals would spread across town.

Wiener’s proposal looks at making new units in just a slice of the city, but another proposal will look at the issue citywide. Chiu’s legislation seeks to take that sea of hidden and unlawful granny flats and bring them up to code, but it wouldn’t look to build new ones.

“The big picture is that we’re exploring legalizing existing [in-law] units that are illegal, to make sure they become safe and protect residents there,” said Amy Chan, an aide in Chiu’s office.

UP TO CODE

Safety isn’t the only consideration, as this could also help the housing supply in the city, those involved told the Guardian. Often these in-law units are rented out to friends and family, and once up to code they’d open up to the market.

But safety is important because these units also often lack city permits because they’re dangerously constructed. Sometimes that can lead to death.

“A lot of time (the units) may not have proper egress for an emergency,” said Dan Lowrey, deputy director of inspection services at the Department of Building Inspection. “We just had a fire last month where three people died because of that.”

Lowrey is part of Chiu’s workgroup that’s navigating the complexities of his new legislation. Just how do you make these units legal? There’s a number of challenges, he said.

When looking at a unit, housing inspectors have a checklist to look through, and some of it is real garden variety stuff. Smoke detectors? Check. Proper floor covering? Check. Those are easy. The real challenge is when there are ceilings that are too low, hallways not wide enough to navigate in an emergency, or the unit has no windows from which to escape in a fire.

That’s when you have an in-law apartment that requires total reconstruction to be brought up to code, a straight up illegal unit. As the law stands now, the only recourse for the city in that case is to evict the people living there.

“That’s the challenge, what do we do with the [in-law apartments] that can’t be legalized?” said Bill Strawn, a spokesperson for DBI. Those are some of the questions that Chiu’s workgroup is tackling now.

The good news, he said, is that there are a good number of units that are up to the Building Code, but not the Planning Code — that’s a much easier hurdle to clear.

The Planning Code basically separates neighborhoods of the city into zones for one, two, or three families in a housing unit. This looks at the amount of available free space, sunlight, air, and parking. With those lifted, many units could be more easily converted to living use.

But finding the units that aren’t up to code is important, said Omar Calimbas, a senior staff attorney at the Asian Law Caucus.

He led the “Our Hidden Communities” study that revealed 33 percent of homes in the Excelsior district contained in-law units, far above the city’s estimates.

His team went door to door and found out for itself. What Calimbas saw was that those living in unregulated units often lived in substandard conditions with nowhere to go for help.

There are some units with no heating, he said. Other times the in-law unit is in a basement barely renovated for use as a living space. Sometimes the bathrooms and shower are really tiny cubes. There are mold and dampness problems.

“You’re living in a space that doesn’t make you feel protected from the elements,” he said. And when the units are made without permits, tenants feel they can’t go to the city for help.

To put it in a nutshell, they are in dire need of regulation. Calimbas is also working with Chiu on his legislation to do just that. But ultimately, each of the two ordinances around secondary units takes small bites out of the housing pie.

Bloom is calling for the city to move aggressively on this issue. “We’re rapidly becoming a more expensive city to live in, more and more so every year.” As more and more San Franciscans are priced out of their homes, time may soon run out.