news@sfbg.com

San Franciscans are poised to vote this November on two important, complicated, and interdependent ballot measures — one a sweeping overhaul of the city’s business tax, the other creating an Affordable Housing Trust Fund that relies on the first measure’s steep increase in business license fees — that were the products of intense backroom negotiations over the last six months.

Mayor Ed Lee and his business community allies sought a revenue-neutral business tax reform measure that might have had to compete against an alternative proposal developed by Sup. John Avalos and his labor and progressive allies, who sought around $40 million in new revenue, although both sides wanted to avoid that fight and find a compromise measure.

Meanwhile, Mayor Lee was having trouble securing business community support for the housing trust fund that he pledged to create during his inaugural address in City Hall in January. So he modified his business tax proposal to bring in $13 million that would be dedicated to the Affordable Housing Trust Fund, but that didn’t satisfy the Avalos camp, who insisted the city needed more general revenue to offset cuts to city services and help with the city’s structural budget deficit.

Less than a day before the competing business reform measures came before the Board of Supervisors on July 24, a compromise was finally struck that would bring $28.5 million a year, with $13 million of that set aside for the affordable housing fund, tying the fate of the two measures together and creating a kumbaya moment at City Hall that was reminiscent of last year’s successful pension reform deal between labor and the business community.

But there was one voice raised at that July 24 meeting, that of Sup. David Campos, who asked questions and expressed concerns over whether this deal will adequately address the “crisis” faced by the working class in a city that will continue to gentrify even if both of these measures pass. Affordable housing construction still won’t meet the long-term needs outlined in the city’s Housing Element that indicates 60 percent of housing construction would need public subsidies to be affordable to current city residents.

It’s also worth asking why a business tax reform measure that doubles the tax base — just 8.4 percent of businesses in San Francisco now pay the payroll tax, whereas 16.4 percent would pay the gross receipts tax that replaces it — doesn’t increase its current funding level of $410 million (the $28.5 million comes from increased business license fees). Some industries — most notably the technology and restaurant industries that have strongly supported Mayor Lee’s political ambitions — could receive substantial tax cuts.

Politics is about compromise, and Avalos tells us that in the current political climate, these measures are the best that we can hope for and worthy of progressive support. And that may be true, but it also indicates that San Francisco will continue to be more welcoming to businesses than the working class residents struggling to remain here.

SOARING HOUSING COSTS

As Mayor Lee acknowledged during his inaugural speech, the boom times in the technology industry has also been driving up commercial and residential rents, he sought to create “housing for the 100 percent.”

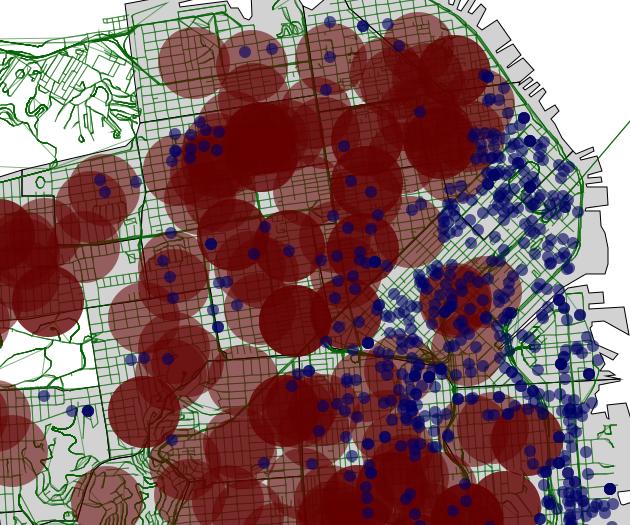

The median rent in San Francisco has been steadily rising, jumping again in June an astounding 12.9 percent over June of last year, according to real estate monitor RealFacts, leaving renters shelling out on average an extra $350 a month to landlords.

Driven by a booming tech industry and a lag in new housing, the average San Francisco apartment now rents for $2,734. That’s an annual increase of $4,000 per unit over last year, in a city that saw the highest jumps in rent nationally in the first quarter of 2012. Even prices for the average studio apartment have edged up to $1,800 a month.

The affordability gap between housing and wages in the city is stark. Somebody spending a quarter of their income on rent would need to be making $85,000 a year just to keep up with the average studio. With a mean wage of $64,820 in the San Francisco metro area, even middle class San Franciscans have a difficult time affording a modest apartment. For the city’s lowest paid workers, even earning the country’s highest minimum wage of $10.25 an hour, even devoting every earned dollar to rent still wouldn’t pay for the average small studio apartment.

For those looking to buy a home in the city, it can be a huge hurdle to put aside a down payment while keeping up with the city’s high rents. Almost 90 percent of San Franciscans cannot afford a market rate home in the city. The average San Francisco home price was up 1.9 percent in June over May, climbing to $713,500, or a leap of $50,000 per unit over last year’s prices.

In the 2010 census, before the recent boom in the local real estate market, San Francisco already ranked third in the nation for worst ratio between income and home ownership prices, behind Honolulu and Santa Cruz.

But as the city leadership grapples to mitigate the tech boom’s effects, the lingering recession and conservative opposition to new taxes have gutted state and federal funds for affordable housing. Capped off last December by the California Legislature’s decision to dissolve the State Redevelopment Agency, a major source of money for creating affordable housing, San Francisco has seen a drop of $56 million in annual affordable housing funds since 2007.

Trying to address dwindling funding for affordable housing, the Board of Supervisors voted 8-2 on July 24 to place the Affordable Housing Trust Fund measure on the fall ballot. Only the most conservative supervisors, Sups. Sean Elsbernd and Carmen Chu, opposed the proposal. Sup. Mark Farrell, who has signaled his support for the measure, was absent.

“Creating a permanent source of revenue to fund the production of housing in San Francisco will ensure that San Francisco is a viable place to live and work for everyone, at every level of the economic spectrum. I applaud the Board of Supervisors,” Mayor Lee said in response.

At the heart of the program, the city hopes to create 9,000 new units of affordable housing over 30 years. The measure would set aside money to help stabilize the ongoing foreclosure crisis and replenish the funds of a down payment assistance program for those earning 80 to 120 percent of the median income.

To do so, the city anticipates spending $1.2 billion over the 30-year lifespan of the program, with a $20 million annual contribution the first year increasing $2.5 million annually in subsequent years. It would fold some existing funding in with new revenue sources, including $13 million yearly from the business tax reform measure. Language in the housing fund measure would allow Mayor Lee to veto it is the business tax reform measure fails.

The board was forced to delay consideration of the business tax measure until July 31 because of changes in the freshly merged measures. That meeting was after Guardian press time, although with nine co-sponsors on the board, its passage seemed assured even before the Budget and Legislative Analysts Office had not yet assessed its impacts, as Campos requested on July 24.

“I do believe that we have to ask certain questions when a proposal of this magnitude comes forward,” Campos said at the hearing, later adding, “When you have a proposal of this magnitude, you’re not going to be able to adjust it for some time, so you want it to be right.”

The report that Campos requested, which came out in the late afternoon before the next day’s hearing, agreed that it would stabilize business tax revenue, but it raised concerns that some small businesses exempt from the payroll tax would pay more under the proposal and that it would create big winners and losers compared to the current system.

For example, it calculated that between the gross receipts tax and business license fee, a sample full service restaurant would pay 69 percent less taxes and a supermarket 33 percent less taxes, while a commercial real estate leasing firm would pay 46.7 percent more tax and a large engineering firm would see its business tax bills more than double.

Board President David Chiu, who has co-sponsored the business tax reform measure with Mayor Lee since its inception, agreed that it is a “once in a decade reform,” calling it a “compromise that reflects the best sense of that word.” And that view, that this is the best compromise city residents can expect, seems to be shared by leaders of various stripes.

BACKING THE COMPROMISE

The business community and fiscally conservative politicians have long called for the replacement of the city payroll tax — which they deride as a “job killer” because it uses labor costs to gauge the size of company’s size and ability to pay taxes — with a gross receipts tax that uses a different gauge. But the devil has been in the details.

Chiu praised the “dozens and dozens and dozens of companies that have worked with us to fine-tune this measure,” and press reports indicate that representatives of major corporations and economic sectors have all spent hours in the closed door meetings shaping the complicated formulas for how they will be taxed, which vary by industry.

When the Guardian made a Sunshine Ordinance request to the Mayor’s Office for a list of all the business representatives that have been involved in the meetings, its spokespersons said no such list exists. They have also asked for a time extension in our request to review all documents associated with the deliberations, delaying the review until next week at the earliest, after the board approves the measure.

But the business community seems to be on board, even though some economic sectors — including real estate firms and big construction companies — are expected to face tax hikes.

“The general reaction has been neutral to favorable, and I expect we’ll be supportive,” Jim Lazarus, the vice president of public policy for the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, who participated in crafting the proposal but who said the Chamber won’t have an official position until it votes later this week.

Lazarus noted the precipitous rise in annual business license fees — the top rate for the largest companies would go from just $500 now to $35,000 under the proposal, going up even more in the future as the Consumer Price Index rises — “but some of it will be offset by a drop in the payroll tax,” Lazarus said.

He also admitted that the new tax system will be “hugely complicated” compared to the payroll tax, with complex formulas that differ by sector and where economic transactions take place. But he said the Chamber has long supported the switch and he was happy to see a compromise.

“I’m assuming it will pass. I don’t believe there will be any major organized opposition to the measure,” Lazarus said.

Labor and progressive leaders also say the measure — which exempts small businesses with less than $1 million in revenue and has a steeply progressive business license fee scale — is a good proposal worth supporting, even if they didn’t get everything they wanted.

“We fared pretty well, the royal ‘we,’ with the mayor starting off from the position that he wanted a revenue-neutral proposition,” Chris Daly, who unsuccessfully championed affordable housing ballot measures as a supervisor before leaving office and becoming the political director for SEIU Local 1021, the largest union of city employees.

Both sides say they gave considerable ground to reach the compromise.

“Did we envision $28.5 million in new revenue? No,” said Lazarus, who had insisted from the beginning that the tax measure be revenue-neutral. “But we also didn’t envision the Affordable Housing Trust Fund.”

Daly and Avalos also said the measures need to be considered in the context of current political and economic realities.

“We were never going to be able to pass — or even to craft — a measure to meet all of the unmet needs in San Francisco,” Daly said. “Given the current political climate, we did very well.”

“If we had a different mayor who was more interested in serving directly the working class of the city, rather than supporting a business class that he hopes will serve all the people, the result might have been different,” Avalos said. “But what’s significant is we have a tax measure that really is progressive.”

Given that “we have an economic system that is based on profits and not human needs,” Avalos said, “This is a good step, better that we’ve had in decades.”

THE HOUSING CRISIS

The tax and housing measures certainly do address progressive priorities — bringing in more revenue and helping create affordable housing — even if some progressives express concerns that conditions in San Francisco could get worse for their vulnerable, working class constituents.

“I don’t know if the proposal before us is aggressive enough in terms of dealing with a crisis,” Campos told his colleagues on July 24 as they discussed the housing measure, later adding, “As good as this is, we are truly facing a crisis and a crisis requires a level of response that I unfortunately don’t think we are providing at this point.”

Not wanting to let “the perfect be the enemy of the good,” Campos said he still wanted to be able to support both measures, urging the board to have a more detailed discussion of their impacts.

“I wish this went further and created even more funding for critically needed affordable housing,” Sup. Eric Mar said before joining Campos in voting for the proposal anyway. “I think they need to build 60 percent of those units as below market rate otherwise we face more working families leaving the city, and the city becoming less diverse.”

Yet affordable housing advocates are desperate for something to replace the $56 million annual loss in affordable housing the city has faced in recent years, creating an immediate need for action and potentially allowing Lee to drive a wedge between the affordable housing advocates and labor if the latter held out for a better deal.

Many have heralded the mayor’s process in bringing together developers, housing advocates, and civic leaders to build a broad political consensus for the measure, particularly given the three affordable housing measures crafted by progressives over the last 10 years were all defeated by voters.

“One of the goals of any measure like this is for it to gain broad enough support to actually pass,” Sup. Scott Wiener said at a Rules Committee hearing on the measure.

In the measure’s grand bargain, developers receive a reduction in the percentage of on-site affordable housing units they are required to build, from 15 percent of units to 12 percent. The city will also buy some new housing units in large projects, paying market rate and then holding them as affordable housing — the buying power of which could be a boon to developers while creating affordable housing units.

At its root, the measure shifts some of the burden of funding affordable housing from developers to a broader tax base and locks in that agreement for 30 years, which could also spur market rate housing development in the process.

A late addition to the proposal by Farrell would create funding to help emergency workers with household earnings up to 150 percent of average median income buy homes in the city, citing a need to have these workers close at hand in the event of an earthquake or other emergency.

While some progressives have grumbled about the givebacks to developers and the high percentage of money going to homebuyer assistance in a city where almost two-thirds of residents rent, affordable housing advocates are pleased with the proposal.

“Did we gain out of this local package? Yes, we got 30 years of local funding. We came out net ahead in an environment where cities are crashing. We essentially caught ourselves way early from the end of redevelopment funds,” said Peter Cohen, executive director of the San Francisco Council of Community Housing Organizations.

Without it, Cohen says many affordable housing projects in the existing pipeline would be lost. “This last year was a bumpy year, and we will not be back to the same operation level for a number of years,” Cohen said. “There was a dip and we are coming out of that dip. It will take us a while to get back up to speed.”

The progressive side was also able to eliminate some of the more controversial items in the original proposal, including provisions that would expand the number of annual condo conversions allowed by the city and encourage rental properties to be converted into tenancies-in-common.

With ballot measures notoriously hard to amend, the Affordable Housing Trust Fund measure is a broad outline with many of the details of how the fund would be administered yet to be filled in. If passed, it will be up to Olson Lee, head of the Mayors Office on Housing and former local head of the demised redevelopment agency, to fill in the details, folding what was essential two partnered affordable housing agencies into a single local unit.

But even the most progressive members of the affordable housing community said there was no other alternative to addressing affordable housing in the wings — which is indeed a crisis now that redevelopment funds are gone — making this measure essential.

As Sara Shortt of the Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco told the Rules Committee, “We lost a very important funding mechanism. We have to replace it. We have no choice.”