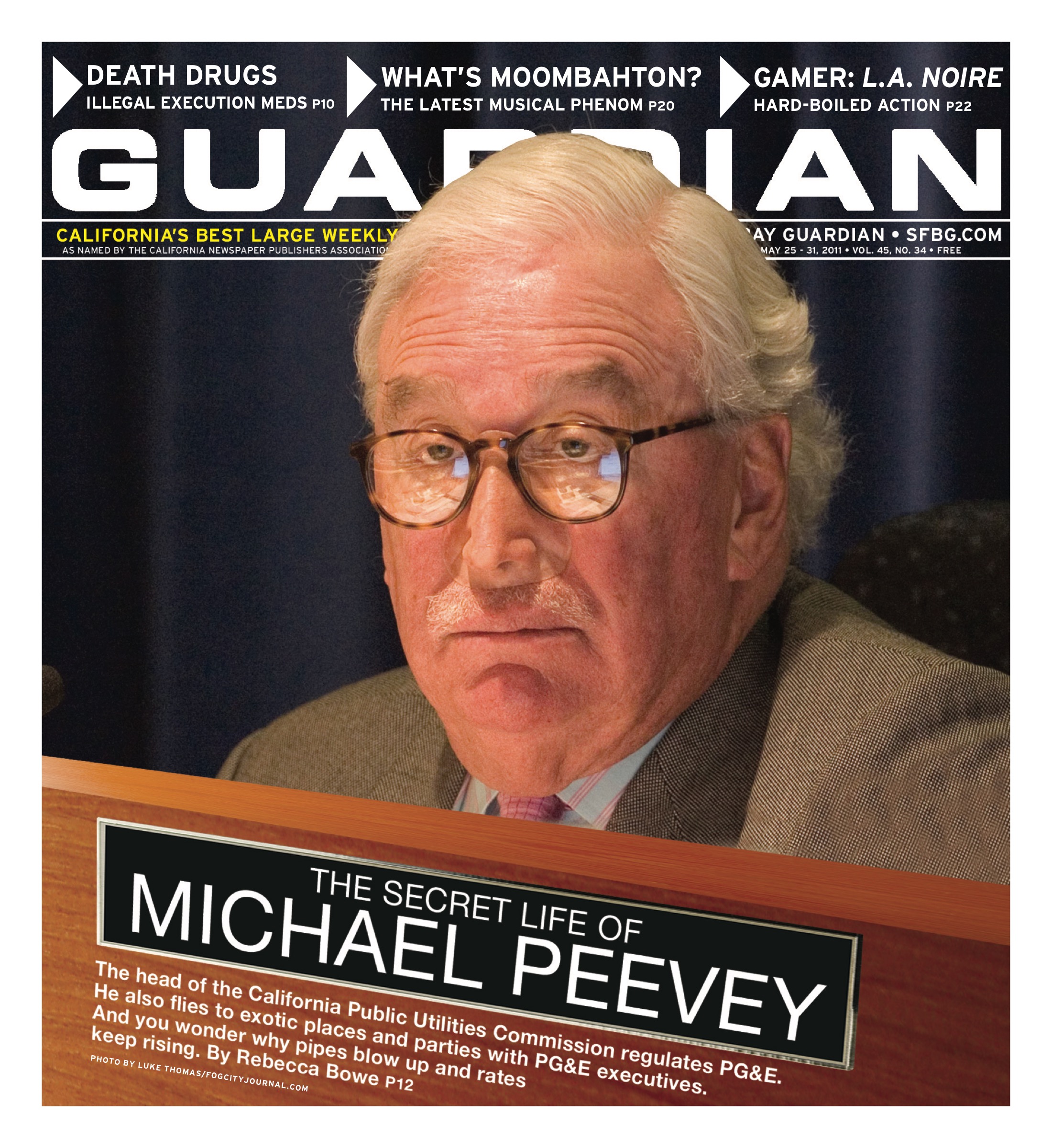

In face of mounting criticism nationwide, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security announced today changes to its Secure Communities (S-Comm) deportation program. These changes include protections for domestic violence victims, and immigrants who are pursuing legitimate civil liberties protections. They give more discretion to ICE prosecutors, create a new detainer form that stipulates in multiple languages that arrestees cannot be detained under an ICE hold for more than 48 hours, except on holiday weekends. The form also requires local law enforcement to provide arrestees with a copy, which has a number to call if they believe their civil rights have been violated. The agency also said it will provide civil rights training related to its S-Comm program at the state and local level.

Immigrant and civil rights advocates said the announcement shows that the administration acknowledges that there are serious problems with S-Comm’s design and implementation. But they charged that the announced reforms fall far short of the S-Comm moratorium that an increasing number of advocates and lawmakers, including California Assemblymember Tom Ammiano, have demanded.

And some advocates expressed concern that the feds’ insistence on expanding S-Comm, in which fingerprints taken by local law enforcement agencies are automatically shared with federal and international databases, is proof that the program is the first step towards rolling out a much larger program called the Next Generation Identification (NGI) initiative.

Under the NGI, the FBI plans to phase-in the deployment of a host of new biometric interoperability capabilities to state and local law enforcement agencies within the next five years. And NGI likely won’t be limited to non-citizens and undocumented immigrants, suggesting that US citizens charged with a crime will also find that once their fingerprints are taken, law enforcement agencies will immediately compile a huge and internationally interconnected dossier on them, regardless of whether they are innocent of the charges.

Civil rights advocates also worry that local enforcement agencies’ participation in S-Comm will become inevitable because S-Comm is simply the first of a number of biometric interoperability systems being brought online by the NGI.

In other words, S-Comm is just the first of many additional information systems that are being made available to local law enforcement agencies to fully and accurately identify suspects in their custody.

And, according to the FBI/CJIS’s own documents, the feds have adopted a three-part strategy to deal with jurisdictions that do not wish to participate:

1. Deploy S-Comm to as many places as possible in the surrounding locale, creating a “ring of interoperability” around the resistant site.

2. Deploy S-Comm selectively to state correctional system facilities, permitting identification of Level 1 offenders who may have been arrested and sentenced in the non-participating jurisdiction,

3. Ensure that the jurisdiction understands that non-participation does not equate to non-deployment.

In other words, though a local law enforcement agency is technically free to shut off, or ignore, the receipt of records related to the fed’s fingerprint-matching capabilities, the feds are already warning local law enforcement agencies that local officers may find themselves “deprived of substantive information relating to an arrested subject’s true identity, place of origin, and other pertinent data of significant law enforcement value.”

Ammiano, who is the author of California’s TRUST Act, which would allow local governments to opt out of S-Comm, said: “Today’s announcement by ICE is simply window dressing. How many more innocent people have to be swept up by the ironically named Secure Communities program before the Obama administration will change course? Talking about the need for comprehensive immigration reform is not an excuse for continuing with a flawed, unjust program that is having tragic consequences for communities across the country. It is time for a moratorium on S-Comm pending a real review of the program not just PR spin from ICE.”

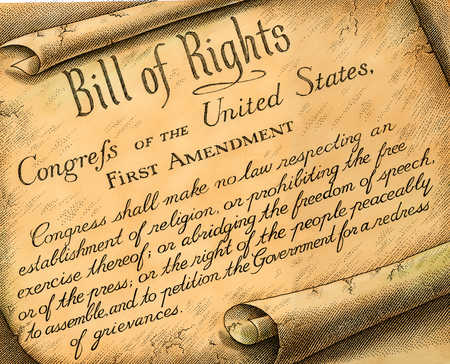

Professor Bill Ong Hing, immigration law expert at the University of San Francisco, stated, “The fact is, under our Constitution, immigration is a federal responsibility. Neither a state like Arizona, nor the federal government itself, can force local governments to act as immigration agents. Such measures compound the injustices of our deeply broken immigration system – and public safety and local resources are among the first casualties.”

And the Asian Law Caucus, the ACLU of California, the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, the California Immigrant Policy Center, and the National Day Laborer Organizing Network released the following joint statement: “We are deeply disappointed by the inadequacy of the Administration’s response to the mounting body of evidence that the ‘Secure’ Communities program is damaging public safety and ensnaring community members. The painful stories of domestic violence victims and other innocent community members facing deportation thanks to S-Comm underscore that the program has simply gone off the rails. While today’s announcement acknowledges that problems exist with the program, the measures outlined by the Administration are a far cry from workable solutions these problems. To announce “reform” before review is an exercise in politics, not policy. The administration should suspend the program and wait for the Inspector General report in order to develop fair and transparent policies.”

“Before vital relationships between local law enforcement and immigrant communities are furthered damaged, before more domestic violence victims, street vendors, family members, and workers who are merely striving for the American dream are swept up for deportation, S-Comm must be reigned in,” the coalition continued. “For the sake of public safety and transparency, we need real solutions. We strongly support California’s TRUST Act, which sets safeguards the federal government has failed to implement and allows local governments out of S-Comm, and we continue to call for a national moratorium on this fundamentally flawed program.”

In recent weeks, Illinois, New York, and Massachusetts, have either pulled out or refused participation in the program while numerous local governments have sought a way out of a deportation dragnet that harms public safety and has operated with no transparency or local oversight. And Ammiano’s TRUST Act, which also sets basic standards for those jurisdictions that do want to participate in S-Comm passed the state Assembly in May and the Senate Public Safety Committee this week.

During today’s press conference, ICE Director John Morton told reporters that “it makes sense to prioritize resources. We don’t have enough resources to remove everyone who is here unlawfully.”

But when the Guardian asked if the reforms address the community criticisms that S-Comm was rolled out as a way to catch serious criminals, but has been largely used to deport non-felons, Morton maintained the S-Comm has always focused on serious criminal offenders, but was never limited to that.

“We remove felony offenders at a higher rate than are convicted in the general population,” he stated. ‘But federal law does not provide that you can come here unlawfully and then commit crimes other than violent crimes.”

True, but local law enforcement agencies have repeatedly observed that you break vital trust with immigrant communities if they believe that contact with police, including being arrested for crimes they did not actually commit, or arrests for very low-level misdemeanors, will lead to deportation.

“This feels like a non-announcement, and it’s far from reform,” said B, Loewe of the National Day Laborers Organizing Network. “You don’t put a collar around a snake and call it a pet.”

And SF Police Commissioner Angela Chan, a staff attorney at the Asian Law Caucus, said the reason ICE and the FBI, “are so crazy for S-Comm is because it’s the first step in a much bigger loop that will include citizens and non-citizens alike.”

NDLON and the Asian Law Caucus are part of the coalition that is calling on the Obama administration to publicly oppose and terminate all programs that create partnerships between state and local law enforcement and the Department of Homeland Security; halt the development of the vast data gathering infrastructure that houses S-Comm, and inform the public of the current scope and purpose of its data collection and dissemination activities; and allow state and local jurisdictions to opt-out of S-Comm.

After today’s press conference, ICE issued a press release stating that through April 30, 2011, more than 77,000 immigrants convicted of crimes, including more than 28,000 convicted of aggravated felony (Level 1) offenses like murder, rape and the sexual abuse of children were removed from the U.S. after identification through S-Comm.

“These removals significantly contributed to a 71 percent increase in the overall percentage of convicted criminals removed by ICE, with 81,000 more criminal removals in FY 2010 than in FY 2008,” ICE stated. “As a result of the increased focus on criminals, this period also included a 23% reduction or 57,000 fewer non-criminal removals.

ICE also observed that the agency currently receives an annual congressional appropriation that is only sufficient to remove a limited number of the more than 10 million individuals estimated to be in the U.S. unlawfully. “As S-Comm is continuing to grow each year, and is currently on track to be implemented nationwide by 2013, refining the program will enable ICE to focus its limited resources on the most serious criminals across the country,” ICE stated.

ICE further noted that it is creating a new advisory committee that will advise ICE on ways to improve S-Comm, including recommending on how to best focus on individuals who pose a true public safety or national security threat. This panel will be composed of chiefs of police, sheriffs, state and local prosecutors, court officials, ICE agents from the field and community and immigration advocates. The first report of this advisory committee will be delivered to the Director of ICE within 45 days.

ICE Director Morton also issued a new memo that directs the exercise of prosecutorial discretion to ensure that victims of and witnesses to crimes are properly protected. The memo clarifies that the exercise of discretion is inappropriate in cases involving threats to public safety, national security and other agency priorities.

And ICE and the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) have created an ongoing quarterly statistical review of the program to examine data for each jurisdiction where S-Comm is activated to identify effectiveness and any indications of potentially improper use of the program. “Statistical outliers in local jurisdictions will be subject to an in-depth analysis and DHS and ICE will take appropriate steps to resolve any issues,” ICE stated.

.