steve@sfbg.com

San Francisco’s future is in the process of being written, once again using lines of computer code and blips on the screens of electronic gadgets, the same as during the last dot-com boom. Its proponents insist it will be different this time — that Boom 2.0 won’t displace the working class, that the bubble won’t burst — but critics have their doubts.

After all, the city completely screwed up the last boom by favoring flashy tech development and growth over the needs of existing, often vulnerable residents. There are already signs that displacement is creeping back, rents are soaring, housing prices are driving people out of town — and even the city’s own economist admits that nobody knows whether the tax-cut driven development will pay for itself.

In many ways, Zendesk, which recently moved to the area, is a poster child for the main obsession of Mayor Ed Lee and other city leaders, who are pushing policies that will make San Francisco the center of a new high-tech expansion. They hope to use that economic growth to create good jobs and address challenges such as revitalizing the mid-Market area.

Lee and Sups. David Chiu and Jane Kim a year ago led the creation of a business-tax exclusion zone intended to keep Twitter from leaving town. The company’s planned growth and relocation to mid-Market, they argued, would be a magnet for more tech companies. The city would give up payroll taxes on the new jobs and provide other taxpayer-financed incentives — but big companies in the zone would be required to enter into community benefits agreements that would help low-income residents and small businesses benefit from the influx of well-paid tech workers.

In fact, a Guardian review of documents (“Behind the tweets,” 3/15/11) found that Twitter resisted the city’s efforts to get a substantial community benefits package, and that deal was pushed back to a later time. The agreement isn’t actually due until the company occupies the new site, and Twitter officials are upbeat about their interactions. Twitter spokesperson Robert Weeks told us by email that the company is working with others to improve mid-Market: “Based on early meetings we’re having with various entities, it’s clear there’s great collective energy that can bring positive change to the neighborhood.”

But Zendesk — a Danish company that makes help-desk support software from an airy third floor office near Market and Sixth streets — seems to be offering a lot to the gritty neighborhood where it opened up shop last year. In January, Zendesk became the first company to take advantage of the tax break and sign a community benefits agreement with the city.

“This is about forming a longstanding relationship with the neighborhood,” said Tiffany Maleshefski, the company’s community benefits manager who negotiated with the city.

The agreement has both general goals and a number of specific requirements. The company will contribute $5,000 to mid-Market community gardens, use local businesses for at least 40 percent of its events, hire two paid interns from the neighborhood, donate equipment to local groups, coordinate several specific outreach events a year, help staff the Tenderloin Tech Lab, and participate in local nonprofit organizations and ventures.

Avoiding payroll taxes on the 66 new employees it’s hired will save the company about $30,000 in its first year, Maleshefski said, and the company plans to grow from about 110 employees in San Francisco now up to about 200 employees by the end of the year.

But CEO Mikkel Svane told us the tax break wasn’t a big factor in choosing this location. He knew they wanted to be in San Francisco and he just liked the space. “The people here want to be a part of a dynamic culture and not on a big campus in Silicon Valley,” he said. “For a technology company, being here where everything is happening is important.”

And even though the new bubble has yet to reach its full proportions, small businesses and nonprofits in the area are already finding landlords jacking up rents in anticipation of the well-heeled new arrivals.

As with the last dot-com boom, some people are going to make a lot of money and spend it around town, and some of it will probably trickle down to the rest of us. But what price will the city and its residents pay for that bump, and what kind of city will this become? Have we really learned anything from the disaster of the first tech boom?

DUELING ECONOMISTS

The question of whether this tech bubble — and Mayor Lee’s focus on jobs — is good for San Francisco involves many realms, but at its center is a question of economics. Does it make economic sense to offer public subsidies and other incentives to boost the tech sector?

We consulted three San Francisco economists with expertise on the situation and a range of perspectives: Tapan Munroe, a business-oriented economist and the author of Dot-Com to Dot-Bomb: Understanding the Dot-Com Boom, Bust, and Resurgence; Peter Donohue, a longtime consultant to cities and unions and principal of PBI Associates; and Ted Egan, the city’s economist.

“I think San Francisco is sitting pretty right now,” Munroe said, noting that tech companies and employees are naturally drawn to this vibrant, culturally rich city. “Young people like to be in San Francisco more than the Silicon Valley…It’s such a unique place, we are so fortunate to live here.”

Monroe said San Francisco is in a league of its own and it doesn’t really have any direct competitors in the region, so tax breaks and other incentives to lure businesses here don’t make much of a difference. High rents and living costs are a factor, he said, but “the main thing the city can provide is quality of life.”

He also doesn’t believe this current tech bubble is going to burst like last time, when the Internet was still new and venture capitalists were throwing money at every kid with a good idea or cool URL. “We’re not seeing anything like that this time,” he said. “Last time, people went crazy.”

This time around, the seemingly crazy stock valuations on tech companies might make more sense: “The global economy is very much being guided by mobile technology. The world is moving to mobility so the valuations have some justification,” he said.

But he added: “The market will speak. If they can’t make money in the next five years, they’ll be gone.”

That’s precisely the concern that many people have voiced, that Twitter will avoid paying taxes to the city as it beefs up and goes public — creating another litter of young millionaires in the process — and that it may fold before its six-year tax holiday ends, leaving little in city coffers. And along the way, the bubble will raise rents and displace the working class.

“Rising prices displace people, that’s just a fact of life,” Monroe said. “That’s the way the market works, but it has social impacts.”

More progressive thinkers dispute that kind of fatalism, saying it isn’t some all-powerful “market forces” that are threatening to remake San Francisco but a certain brand of speculative, monopolistic capitalism that is being aggressively pushed by a handful of wealthy investors and their political partners.

In the latest Harper’s Magazine cover story, “Killing the Competition: How the new monopolies are destroying open markets,” writer Barry Lynn argues that the consolidation of wealth and dismantling of fair trade and pro-labor laws has allowed the Bay Area tech industry to unfairly dominate small competitors and control the labor market.

That trend has been masked by political euphemisms that fool the public. “Corporate monopoly? Let’s just call that the ‘free market.’ The political ravages of corporate power? Those could be recast as the essentially benign workings of ‘market forces,'” Lynn wrote.

Donohue has been calling out such rhetoric for decades. He told us the city’s economic development policies are mostly a boon to politically connected landlords and investors, and there’s been remarkably little discussion at City Hall about gentrification, increased demand for city services, or other problems created by economic bubbles.

“People say it’s different this time, but they say that every time. It’s not different,” Donohue told us. He said economic bubbles usually hurt the poor and working class by driving up the cost of living. And he also said, “Even the most conservative economists don’t like the idea of subsidizing businesses because they think it’s a distortion of the market.”

Yet the “jobs” rhetoric and assumption that government should actively promote and subsidize the private sector has broad support in City Hall these days, even though Donohue said few people are stopping to ask whether a new tech bubble is actually good for the city.

“When you bring a lot of people into an area, you’re going to create a demand for public services,” Donohue said. “I don’t think anyone has done a very good assessment of what this will cost the city.”

Donohue worked on a political campaign in the mid-’80s to require a study of the costs to the city of serving commercial growth that was occurring in the Financial District at the time, but he said it was bitterly opposed by then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein and her downtown allies. “Nobody seems to want to know what that figure is,” Donohue said. “Nobody at City Hall is even asking the question.”

City Economist Ted Egan confirmed that his analysis of the mid-Market tax break and other economic development schemes doesn’t include the cost of increased demands on city services. “I’ve never dealt directly with that argument,” Egan told us.

Based on his assumption that Twitter’s move to the SF Mart building (owned by the politically connected Shorenstein family) on Market between Ninth and 10th Streets will fill up commercial vacancies throughout the area and generate increased sales, property, and payroll taxes, Egan concluded the city will more than make up for the lost business tax revenue over the long run.

He minimized the importance of costs to the city, such as increased police or sanitation services, and impacts to city infrastructure from water and sewer to roads and public transit. “It can’t be that running more transit is bad in a transit-first city,” Egan said, noting the relatively fixed cost of operating a Muni station.

Yet Donohue and others say the fact that the city and San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency have huge budget deficits to close every year, even after years of cutting services and raising fees, indicates the city has a structural budget deficit that will only get worse as growth places more demands on government.

“I don’t think these things are well-thought-through, ever,” Donohue said.

Lee, Kim, and representatives from the Mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development didn’t return our calls, but Chiu did and he said he believes in actively courting the tech industry with public incentives: “My support for these policies is a belief that it will broadly benefit San Franciscans.”

Yet when asked why the city doesn’t consider its costs or the impacts of rising rents and living costs, Chiu spoke only in generalities, saying that he’s been engaged in many recent meetings “to make sure we do heed the lessons of the last tech boom and make sure a rising tide lifts all boats.”

RISING TIDE

One of the most obvious negative impacts of the last tech boom was residents, nonprofits, and small businesses being hurt by rising rents and other costs, and there are some indications that’s already happening again.

The director of a venerable local nonprofit in the mid-Market area that is in the process of renewing its office lease told us their landlord is trying to nearly double the rent of $18 a square foot. “There’s all this venture capital now and people are willing to pay $33 per square foot, so landlords are just seeing green,” said the director, who asked not to be identified because negotiations are ongoing. “The speculation is hitting us big time. The neighborhood is all aTwitter, and they’re treating us like junk mail.”

Egan said he predicted those rising rents, but he didn’t think they would happen so quickly. “In principle, it doesn’t surprise me, but it does surprise me that it’s happened that far and that fast,” Egan said. “The idea was to create employment, rather than rising rents.”

Chiu said he was also surprised. “Jane Kim and I very much want to monitor the situation. We will look into city policies that will mitigate this trend,” he said. When asked what the city can do, he made several vague statements before saying, “If we’re serious about diversity, we may want to talk about rent subsidies at some point.”

That would be one more cost to the city, adding to a toll that Donohue and others say is being ignored. Chiu, Egan, and other city officials seem to think growth is the only way forward. As Egan said, “If we don’t do development in a city like San Francisco, what happens?”

But others say San Francisco should take care of its own first to maintain the city’s diversity. Asked what the city’s approach to economic development should be, Donohue said, “I’d presume you want to serve the people who live here already.”

It was an idea echoed by Chris Daly, who was a housing activist during the last dot-com bubble before being part of wave of progressive politicians its backlash propelled onto the Board of Supervisors. He is now political director for SEIU Local 1021, which represents city workers.

“If your priority is to care for the fabric of the city as it’s been built, you invest in what’s here now,” Daly told us. “My view is when the city courts the high-tech industry to try to jumpstart the city’s economy, there are significant ramifications to what kind of city you’re building.”

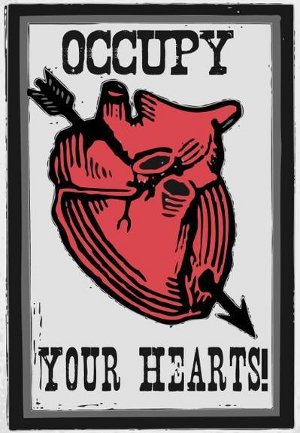

Local progressive activists, people who often work to counter the impacts of those who see San Francisco as simply a place to make money, agree that there is a perverse logic at play these days.

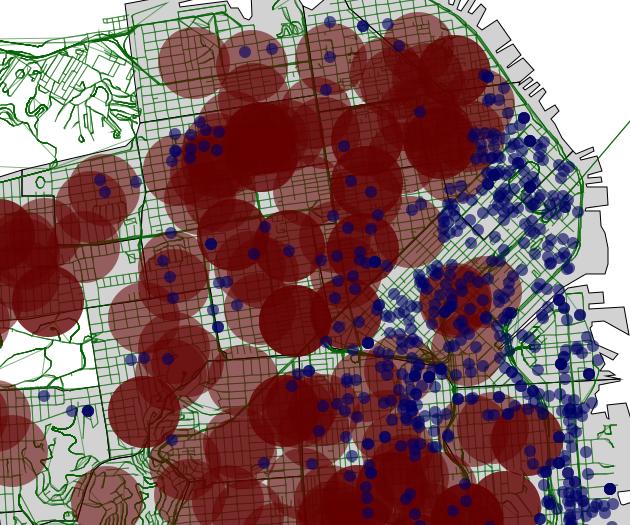

“We already have more jobs than people,” said Marc Salomon, a computer programmer and longtime community activist, noting that the city has about 800,000 residents and about 1.3 million people who work here. “And we have lots of unemployed San Franciscans, and we have a budget deficit.”

Tom Radulovich, executive director of Livable City, said the simplistic rhetoric coming out of City Hall masks the more complex realities that the city faces. “When they say ‘jobs,’ everyone’s critical thinking sensibilities are supposed to shut off,” Radulovich said

Rather than focusing solely on whether a proposal creates private sector jobs, he said that a more complete analysis involves what he calls the “three Es: equity, environment, and economy.” In other words, does the proposal have broad, leveling benefits (equity), what are its impacts to the natural and built worlds (environment), and what are its fiscal implications (economy).

“But,” he said, “we’ve been privileging that third ‘e’.”