- No categories

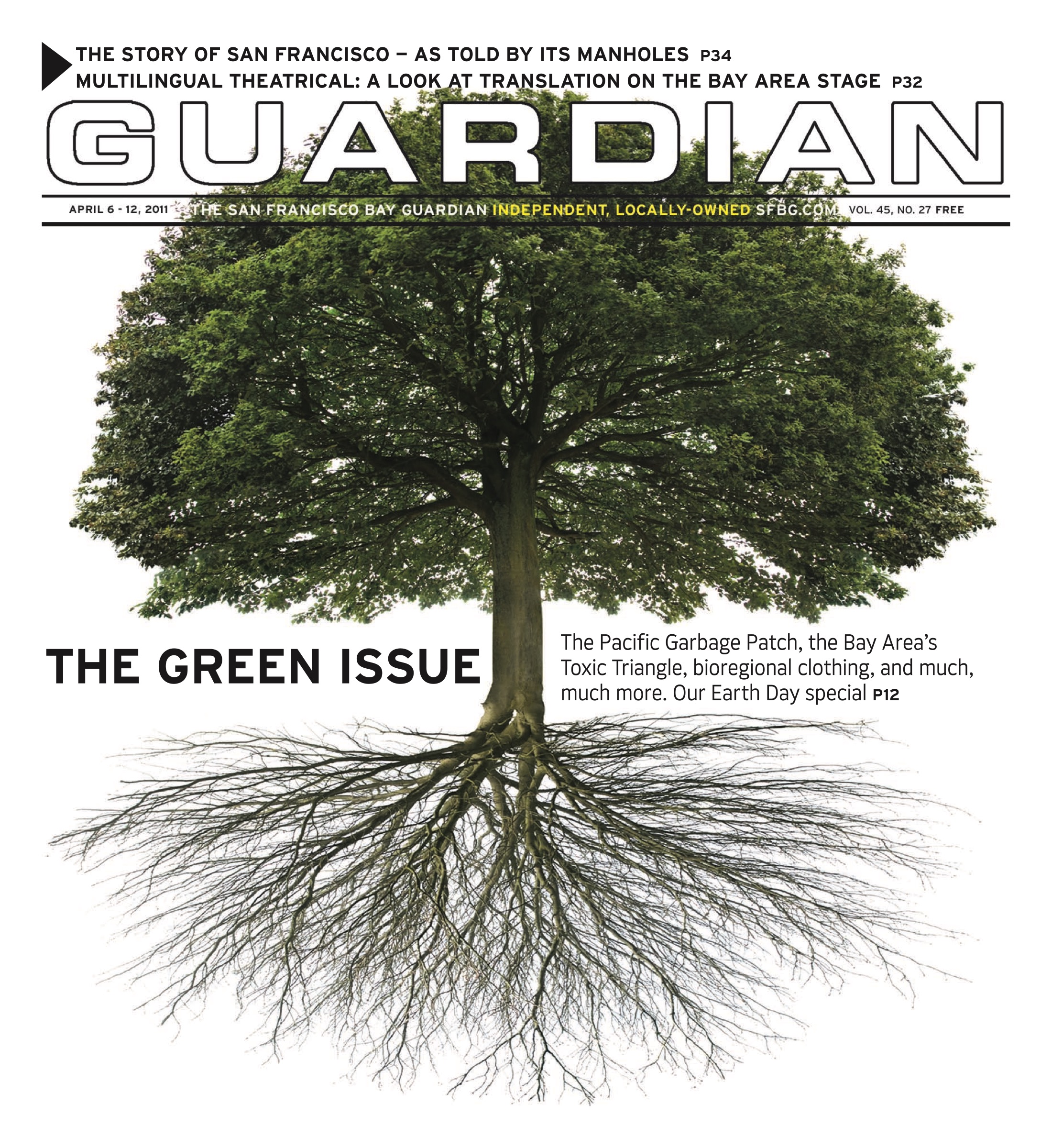

Green City

Beyond 420

steve@sfbg.com

GREEN CITY When the clock or the calendar hits 420 — and particularly at that magical moment of 4:20 p.m. on April 20 — the air of Northern California fills with the fragrant smell of green buds being set ablaze. But this year, some longtime cannabis advocates are trying to focus the public’s attention on images other than stoners getting high.

“I hope the house of hemp will replace the six-foot-long burning joint as the symbol of 420,” says Steve DeAngelo, executive director of Harborside Health Center, an Oakland cannabis collective, and one of the organizers of an April 23 festival in Richmond dubbed Deep Green that offers an expanded view of cannabis culture.

In addition to big musical acts, guest speakers, and vendors covering just about every aspect of the cannabis industry, the event will feature a house made almost entirely of industrial hemp. That exhibit and many others will highlight the myriad environmental and economic benefits of legalizing hemp, as California Sen. Mark Leno has been trying to do for years, with his latest effort, SB676, The California Industrial Hemp Farming Act, clearing the Senate Agriculture Committee on a 5–1 vote April 5.

Public opinion polls show overwhelming support for ending the war on drugs, particularly as it pertains to socially benign substances like industrial hemp, a strain of cannabis that doesn’t share the psychoactive qualities of its intoxicating sister plants. Yet DeAngelo said that after 40 years of advocating for legalization, he’s learned to be patient because “unfortunately, our politicians are lagging behind public opinion.”

In San Francisco and many other cities, marijuana dispensaries have become a legitimate and important part of the business community (see “Marijuana goes mainstream,” 1/27/10), spawning offshoots like the edibles industry that provide more safe and effective ways of ingesting marijuana (see “Haute pot,” 1/25/11).

But the proof that the medical marijuana is about more than just getting people high also continues to grow, from the endless touching tales of cancer, AIDS, and other patients who have been saved from suffering by this wonder weed to the lengths that the industry is going to cultivate cannabidiol (CBD), a compound found in marijuana that doesn’t get people high but offers many other benefits, including acting as an antidepressant and antiinflammatory medicine.

CBD and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive compound in marijuana, generally have an inverse relationship in cannabis plants, so the efforts by generations’ worth of pot cultivators to breed strains with higher THC content have almost completely bred the CBD out of the plants. “In the underground markets, it didn’t have any value,” DeAngelo said.

When Harborside Health Center first started laboratory-testing marijuana many years ago, DeAngelo said that of 2,000 strains tested, only nine had “appreciable quantities of CBD.” In addition to efforts by Harborside and the San Francisco Patient and Resource Center (SPARC) to work with growers on bringing back CBD-heavy strains, modern scientific techniques are allowing CBD to be extracted from the strains that do exist.

“It’s not psychoactive, but let me tell you, it is mood-altering,” says Albert Coles, founder of CBD Sciences in Stinson Beach. “A lot of people, when they smoke pot go inward, but that often isn’t good for social interactions.”

His company makes laboratory-tested cannabis tinctures called Alta California that have been increasingly popular in San Francisco, offering three different varieties: high THC/low CBD, low THC/high CBD, and a 50-50 mix. “It’s good for creative thinking because it just clears out all the noise,” Coles said of CBD.

But even when talking about THC, many in the industry dispute the criticism that most marijuana use is merely recreational drug use. Vapor Room founder Martin Olive has said most pot use isn’t strictly medical or recreational, but a third category he calls “therapeutic,” people who smoke pot to help cope with the stress of modern life.

DeAngelo agrees, although he puts it slightly differently: “The vast majority of cannabis users use it for the purpose of wellness.”

DEEP GREEN FESTIVAL Saturday, April 23. Performances by The Coup, Heavyweight Dub Champion, and more; speakers include pot cultivation columnist Ed Rosenthal, Steve DeAngelo, and business owner David Bronner. $20 advance/$30 door ($20 for bicyclists and carpoolers, $100 VIP).

Craneway Pavilion, 1414 Harbour Way South, Richmond. www.deepgreenfest.com

Green today, gone tomorrow

culture@sfbg.com

URBAN FARMING Green thumbs may soon be mourning the partial removal of Hayes Valley Farm. The urban agriculture education project is facing the prospect of condos being built on one of its two sections of city-issued property by Bay Area development company Build Inc., as early as February 2012. The company has been slated to build on the property since before the farm project began in January 2010, but was delayed by the recession of 2008 and its wet-blanket effects on new construction projects.

Today the farm sits on 2.2 shady acres near the heart of the Hayes Valley neighborhood. Visit on a typical day and you’ll find volunteers planting fava beans, school-age kids wandering through crops and trees on a school tour, perhaps a instructor teaching a beekeeping class, and on Sundays, a group of volunteers distributing free produce to anyone who stops by. All the while, plant and animal life buzz amid the fertile urban enclave.

But while volunteers have put hundreds of hours into making the farm what it is today — even going so far as to purify the car exhaust-infused soils to make the land arable — this green space was never intended for long-term use. Hayes Valley Farm is among a handful of ventures around the city — another one is interdisciplinary collective Rebar’s Showplace Triangle, a street at the base of Potrero Hill that has been turned into a pedestrian zone with repurposed benches and planter beds as part of the group’s Pavement to Parks project — that are aimed at making interim public space out of underutilized properties.

The current story of the land that the farm occupies starts with the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. The quake’s damage to the Central Freeway resulted in the city acquiring major parcels of land where the thoroughfare once stood. Since then, the city has relied on sales of those properties — which it designated as Parcels A to V — to build Octavia Boulevard and redevelop the Hayes Valley-Market Street neighborhood. Half the land was to be made into affordable housing.

But at one point, the neighborhood noticed that some of the parcels awaiting sale were attracting crime, graffiti, dumping, and otherwise unsavory activities. The Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association teamed up with the Mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development to go looking for potential projects that could put these spaces to constructive use during the time that they awaiting development.

“We went out and actually sought a user for this. We got in contact with Jay Rosenberg and Chris Burley, who were interested in doing the farm, and we brought them here and asked them if this was doable,” says Rich Hillis of the Office of Economic and Workforce Development. “We were 100 percent clear that it was going to be for interim use only, and they embraced that.” Hillis and colleague Ken Rich ensured that Hayes Valley Farm received a $50,000 grant from the Mayor’s Office to get started on the work of clearing the property and setting up community programming on the land.

While it’s clear that the farm project was meant from the get-go to be an interim use for Parcels O and P, some members of the community are upset to see Parcel P turned over so soon to Build Inc. “As a citizen, I have the freedom of being able to ask what’s better for the community, this farm or more developments?” says Morgan Fitzgibbons, head of the neighborhood sustainability group the Wigg Party and farm volunteer. “The farm is an anchor of a burgeoning sustainability movement, and after seeing all the good it can do, are we still going to go in there and build? I think the issue is bigger than one city block.”

But Booka Alon, who is part of the 10 core farm volunteers who manage and run the farm, says they will not be putting up a fight. “We are very grateful to the Mayor’s Office and we’re ready to leave when asked. That’s part of our agreement.”

Alon says that the farm gives a sense of hopefulness and accomplishment to many young volunteers who are otherwise underemployed during the economic downturn, but turning Hayes Valley Farm into a long-term career commitment is not something many volunteers are itching to take on. “Planting and farming are hopeful acts, but not very lucrative in an urban setting.”

Many community members who championed the farm in the first place hope that the transition of Parcel P to Build Inc. will go smoothly so that other interim-use projects will be supported in the future. “We love the farm,” says Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association member Jim Warshell. “What they’ve done has been spectacular and wonderful, but that doesn’t mean that you don’t honor your commitment. The way we respond to Parcel P will affect how people trust us with future deals.” And while the farm’s popularity among city residents can’t be denied, some look forward to the fruition of the city’s promise that the area will be converted into homes that residents can afford.

But the sun hasn’t set on the work of Hayes Valley Farm. The group is collaborating with the city on finding another location to continue planting and teaching. And the future of Parcel O appears to be some shade of green. For now, there are no imminent development plans for the space and, unlike Parcel P, Parcel O is under the auspices of the city’s Redevelopment Agency, not a private company.

Alon says that some of the plant beds and flowers on Parcel O might someday be incorporated into the mixed-income housing developments that will eventually stand around — and possibly on — it. As for the permaculture soil that the farm hands have diligently created, she hopes it can be recycled along with the knowledge that was shared through the project. “Maybe we’ll give the soil to neighbors when it’s over. They can use it in their own gardens.”

For more information on how to support the farm, visit www.hayesvalleyfarm.com.

Working on it

caitlin@sfbg.com

GREEN ISSUE With the recession fast seeping into the everyday fabric of American life (or at least Monday through Friday’s fabric), the enthusiasm that the term “green jobs” generates can be well understood. But can we really call a $10 hourly pay rate for installing solar panels sustainable? And what would be the bigger of the two triumphs: creating a carbon-free country or a more equitable nation? With partnerships springing up across the country like the Blue Green Alliance, created by the United Steelworkers and the Sierra Club, maybe the two goals aren’t so separate after all. Here are some West Coast organizations fighting to make sure that the environmentally-friendly jobs that do exist — and have yet to be created — pay a decent wage.

OAKLAND GREEN JOBS CORPS

Created by the long-time civil rights champions at the Ella Baker Center and other community partners, this program recruits poor young adults to a 38-week course of study that recognizes what it takes to break the cycle of unemployment. Participants begin with classes in basic job skills, literacy, and substance abuse counseling, then continue on to classes at Laney College in basic construction skills, eco-literacy, and specialized green building practices. At graduation, participants are hooked up with well-paying jobs in the green construction sector or traditional building trade union apprenticeships — where their newfound environment-saving skills will make them leaders in the years to come.

CALIFORNIA INTERFAITH POWER AND LIGHT

Pray for change — or change the way you pray? Created 10 years ago in SF, CIPL, whose work has since spread to 38 state affiliates, aides faith communities of all denominations in greening their place of worship. Greatest hits include installing a geothermal heating system in a Berkeley synagogue, work on First Chinese Baptist Church in San Francisco, and tricking out a Bayview-Hunters Point church with solar panels on the congregation’s extremely limited budget. Workers hired to make the holy places sing a song of sustainability are usually sourced from organizations like Richmond Build, which provides training to many people living in public housing and with criminal records.

APOLLO ALLIANCE

Apollo Alliance, another nationwide coalition-building organization that got its start in SF, is making green jobs happen in Los Angeles — with or without federal dollars. The group sponsored the city’s Green Retrofit and Workforce ordinance, which required that municipal buildings achieve LEED certification at the silver level or higher, prioritizing updates on the buildings that were near areas with low income and high unemployment rates. Linked directly to workforce training programs, the ordinance is already under attack in Washington by H.R.1, a bill that would strip its funding. But L.A. is making the first move on the threat — the city is hoping to fund the successful program through energy conservation bonds.

GREEN FOR ALL

Erstwhile Obama appointee, environmental rock star, and Ella Baker Center founder Van Jones started this organization in 2008 to place the war on poverty at the heart of the sustainability movement. Sure, with offices around the country, it’s not exactly local. But the group plays an important role supporting nationwide policies that will make green jobs fair and just for workers. Plus, it led the charge against last year’s Prop. 23 challenge to the growth of green technologies, taking to the road in a bus that interviewed community members and green energy experts in 10 Californian cities. Plus, it kicked ass with a media campaign smart enough to best the bummers at PG&E and other public utilities.

Threads of change

rebeccab@sfbg.com ; caitlin@sfbg.com

GREEN ISSUE Planting indigo seedlings in a leaky greenhouse in the mist of a cold Marin County afternoon, Rebecca Burgess thinks about what she’s going to wear. She’s not a fashion model, or a clotheshorse, but she is on a yearlong quest to attire herself only in garments that were sourced and produced bio-regionally — or within a 150-mile radius of home — an area she calls her local fibershed.

Why take on such a challenge? “If we don’t want BP oil spills, it’s about more than just not fueling our cars with it,” Burgess says. While many activists seeking to unplug from oil dependency have worked to encourage bicycles, local agriculture, and reusable shopping bags, her approach takes on the materials we use to clothe our bodies.

Half of all jeans sold annually in the United States — around 200 million pairs — are produced in the Xintang township in China’s Pearl River Delta, where a Greenpeace study found hazardous organic chemicals and acidic runoff in the watershed, both of which may contribute to profound health risks for factory workers and their communities.

Of course, oil is consumed in the transport of factory-made garments halfway across the globe. But as Burgess notes, that’s only part of the reason for her project, which so far has yielded a book on the making of natural dyes and a plan for a community cotton mill in Point Reyes.

She’s also concerned about the synthetic fibers mass-manufactured clothes are made of. “We’re wearing a lot of plastic,” she notes. Not just plastic: petrochemicals, formaldehyde, and carcinogenic polycrylonitriles can all be used to produce your outfit— materials that seep into your pores when you’re active and can hardly be considered ideal to wear against your skin.

To limit support of the oil-reliant garment industry, Burgess envisions a collaboratively created source of clothing made from materials and processes that are — unlike the heavy-metal laden industrial effluent from denim dyes flowing into China’s Pearl River — completely nontoxic. To that end, she’s linking natural fiber artisans and raw material providers throughout the region with the fibershed project, which aims to bolster local clothing production.

Today, she’s the poster child for her effort. Burgess sports striped alpaca kneesocks, an organic cotton skirt sewn by a friend, and a wool sweater her mom knitted with handmade yarn, sourced from a sheep farmer they know. The clothes look well-loved, which makes sense: relying on one’s fibershed for a wardrobe is not easy. When Burgess first embarked on her yearlong bioregional clothing challenge, there wasn’t much in her dresser. “I lived out of three garments for weeks,” she laughs. “People were like, ‘You’re wearing the same thing over and over and over again.'<0x2009>”

But she found that she wasn’t the only one who believed that a change was possible in our closets. Friends, family, and a wider community of shepherds, cotton growers, knitters, seamstresses, and artisans all pitched in to help her along with the project. Burgess says this growing network underlies what it will take for communities to transition to a more sustainable lifestyle. “All this is about encouraging more relationships.”

There’s Sally Fox, whose non-genetically modified colored cotton operation in the Capay Valley is the culmination of years of seed-selecting for natural color tones. There’s the 96-year old sheep farmer in Ukiah. Not to mention the hip fiber artisans based in Oakland and the young fashion students in San Francisco who were inspired by her project.

“It’s not just of value to an old spinster community, it’s of value to a young, hip generation of people who want to live in a carbon-free economy,” Burgess notes. “A bunch of urban young people are really into fibers.” Most, she adds, are women.

Burgess makes her own clothing, too, and to research her book (Harvesting Color, Artisan, 180 p., $22.95) traversed the country learning from female “wisdom-keepers,” women whose craft practices were based on passed-down traditions encouraging the health of their ecosystems.

Today is part of her latest endeavor: growing her own indigo dye so that locally made garments can be dyed blue sustainably. Her day’s work entails planting 400 indigo seeds in flats filled with soil from a ranch down the road. This spring and summer, she plans to raise 1,000 indigo plants in three garden plots just outside the greenhouse. The day the Guardian came to visit, sheep lounged in the pasture beyond her garden plots, as if to illustrate the point that this process won’t require any long-distance transport.

She realizes that few people have a greenhouse to plant indigo in, much less the time necessary to produce their own clothing — or the money needed to dress in handcrafted pieces. But by proving that it’s possible to wear clothes that were created by your own community, she hopes that people will at least “settle for second best, which in this case is wearing organic, American-made materials.”

Even that would be something — right now clothes just aren’t on most of our sustainability compasses. As an example, Burgess recalls a panel discussion she attended at which sustainable food champions Michael Pollan and Joel Salatin were speakers. Someone (“And it wasn’t even me!” she insists) asked them what role garments played in a sustainable lifestyle. “And they were speechless. They didn’t have a thing to say.”

It was a PR challenge Burgess was happy to assume — she has since struck up an e-mail correspondence with Pollan, which she hopes will spread her message further. “Clearly we need some education.”

Join Burgess and other yarn producers for a locally made fashion show and to see plans for their community mill May 1 at Toby’s Feed Barn in Point Reyes. For more information call (415) 259-5849 or visit www.rebeccarburgess.com

Drawing a line in the toxic triangle

rebeccab@sfbg.com

GREEN ISSUE California is often viewed as being among the brightest shades of green. The Golden State’s landmark climate-change legislation has proven magnetic for green-tech startups, while Northern California is defined in part by its longstanding love affair with natural foods and solar power. San Francisco boasts a well-used network of bike routes, a ban on plastic bags, mandated composting of kitchen scraps, and a host of urban agriculture projects.

While much of the Bay Area’s environmental reputation is well-deserved, things look different from poor neighborhoods where homes are clustered beside hulking industrial facilities and public health suffers. For years, grassroots organizations working in Richmond, Oakland, and Bayview-Hunters Point have sought to improve air quality and promote environmental justice in neighborhoods plagued by higher-than-average rates of respiratory disease, cancer, and other preventable illnesses.

The Rev. Daniel Buford of Oakland’s Allen Temple Baptist Church told the Guardian that he began talking about the polluted areas of Richmond, Oakland, and San Francisco as a “toxic triangle” two decades ago. It was an analogy, he explained, that plays off the mysterious deaths that the Bermuda Triangle is famous for. Yet the label also served a purpose — to unite three communities of color that were fighting separate yet similar battles against health hazards associated with their surroundings.

“There were a lot of things that weren’t in place with public consciousness that are in place now,” Buford said.

Today, he isn’t the only one uttering the catch phrase. A host of community organizations banded together as the Toxic Triangle Coalition last year to organize three forums on environmental justice in the three cities. Advocates cast the neighborhood-specific problems as three parts of a regionwide phenomenon, highlighting how pollution from shipping, crude oil processing, freeway transportation, abandoned manufacturing sites, hazardous waste handlers, and other industrial facilities disproportionately affect communities of color, where poverty and unemployment rates are already high.

Buford views the Toxic Triangle Coalition as a strategy to mount pressure for stronger enforcement of environmental laws in disproportionately affected areas. “We live in the whole Bay Area — we don’t live in one little part of the Bay Area,” he noted. “Our coalition strongly urges our state representatives in each of the counties to call for a hearing at the state level.”

OIL WARS

In Richmond, California’s top greenhouse-gas emitter looms as an expansive backdrop of the city, a tangled network of smokestacks and machinery near a hillside cluster of large, cylindrical oil storage containers. Chevron Corporation’s Richmond Refinery was built more than a century ago. A few years ago, the oil company began making noise about how it was in need of an upgrade.

Weaving through a blue-collar residential area of Richmond in her sedan, Jessica Guadalupe Tovar recounted how Communities for a Better Environment (CBE), the nonprofit she works for, revealed that Chevron hadn’t told the whole story when it was petitioning for a permit to expand the refinery. The oil company’s long-term goals, CBE learned from a financial report, included gaining capability to process thicker crude that tends to be sourced from places like Canada’s Alberta tar sands.

“We call it dirty crude,” she said. “But it’s really dirtier crude.”

Converting thicker crude to fuel requires higher temperatures and pressures — and that translates to higher greenhouse-gas emissions and a heightened risk of flaring and fires.

The refinery expansion could have meant an air-quality situation going from bad to worse. Public health problems such as asthma and cancer have spurred campaigns led by the West County Toxics Coalition, CBE, and other environmental justice groups. Tovar explained how CBE orchestrated an air-monitoring program in 2006, collecting samples from 40 homes in Richmond and 10 in Bolinas as a point of comparison.

While trace amounts of chemicals from household cleaners were present in both, samples from the Richmond residences also contained the same toxic compounds that spew from Chevron’s refinery. “We found pollution known to come from the oil refinery settling inside people’s homes,” Tovar explained. “Once it’s trapped in your home, it starts to accumulate.”

Chevron won its expansion permit by a slim margin in 2008 with a city council dominated by officials who had reputations for being friendly to the oil giant. Yet environmental organizations filed suit, saying the environmental impact report (EIR) approval was based on was illegal because it failed to analyze the company’s likely plans for heavier crude processing. A Contra Costa County judge ruled in favor of the environmentalists, halting the expansion project in 2009. Chevron appealed, but the decision was upheld in 2010.

Stopping the expansion was a substantial victory, but environmental justice advocates remain wary of Chevron — particularly after the company attempted to blame job losses on the green coalition that filed suit. “Chevron pit workers against us,” Tovar noted. “And also started saying, ‘This is why environmental laws are bad for the economy.'”

GLOBAL TRADE, LOCAL FUMES

Each day, the Port of Oakland fills with trucks waiting to load up on goods shipped in from around the globe on massive cargo vessels. It’s a local symbol of a globalized economy. But for the West Oakland neighborhoods surrounding the port, the daily gathering of diesel rigs means an unhealthy infusion of particulate matter into the air.

A report issued by the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy (EBASE), the Pacific Institute, and the Coalition for Clean and Safe Ports found that West Oakland residents are exposed to particulate matter concentrations nearly three times higher than the regional average. Health studies have shown that asthma rates in West Oakland are five times higher than that of people living in the Oakland hills, and cancer risks are threefold compared to other Bay Area cities. For the truck drivers, the risk of cancer is significantly higher than average.

A state air-quality law that went into effect in early 2010 banned pre-1994, heavily polluting diesel trucks from the port, thanks in part to years of environmental campaigning that has publicized public-health impacts associated with the diesel pollution. Yet the new regulation brought an unintended consequence: for truck drivers who must purchase their own gas and pay for their own upgrades, the new rule was ruinous. A survey by the Public Welfare Foundation found that since the new environmental regulation went into effect, 25 percent of Oakland truck drivers had declared bankruptcy, been evicted, or faced foreclosure.

Retrofitting the trucks with new air filters is a five-figure prospect, while the cost of a new truck can clear $100,000. “At the end of the day … a lot of them will only take home about $25,000 a year,” explained EBASE spokesperson Nikki Bas. “It’s an immigrant workforce who are living in poverty.”

So the Coalition for Clean and Safe Ports, which pushed for tougher air-quality regulations, is now pressuring for a reform of the trucking industry to place the cost of clean upgrades onto powerful trucking companies instead of low-wage drivers. The coalition’s campaign has sought to link the needs of the drivers and the surrounding community, organizing rallies with blue-green signs bearing the motto “Good Jobs & Clean Air” to call for a change to the truckers’ employment classification from independent contractors to employees, which would shift the cost of compliance onto employers instead of drivers.

West Oakland isn’t the only East Bay area inflicted by excessive levels of diesel particulate matter from trucks entering the Port of Oakland. The fumes also affect East Oakland neighborhoods bisected by the big rigs’ primary thoroughfares. In addition to truck traffic and freeways, East Oakland is also the site of numerous hazardous-waste handlers and abandoned industrial sites.

Nehanda Imara, an organizer with CBE who also helped put together the Toxic Triangle Coalition forums, described how her organization recruited volunteers to count the number of trucks passing through a heavily traveled East Oakland strip as a way to quantify the source of particulate matter pollution. They reached a tally of around 11,700 over the course of 10 days.

Some progress has been made to limit the exposure of diesel pollution for East Oakland residents. The city is working on a comprehensive plan to assess trucking routes, and a campaign to limit truck idling is helping to limit unnecessary tailpipe emissions.

Yet youth hospitalizations for asthma in East Oakland are 150 percent to 200 percent higher than Alameda County taken as a whole, and an air-monitoring project in that area revealed high levels of particulate matter exceeding state and federal standards.

“That’s also an environmental injustice,” Imara said. “When the laws are there, but not being enforced.”

TOXIC SOUP

In San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood, environmental justice groups have spotlighted the toxic stew associated with the naval shipyard and other pollution sources for years. A 2004 report produced jointly by Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice, the Bayview-Hunters Point Mothers Environmental Justice Committee, and the Huntersview Tenants Association outlined a “toxic inventory” of the area. The inventory depicts a more complicated web of toxic sources than the asbestos dust and naval shipyard cleanup that have been focal points of news coverage surrounding Lennar Corp.’s massive redevelopment plans for that neighborhood.

“Over half of the land in San Francisco that is zoned for industrial use is in Bayview-Hunters Point,” this report noted. “The neighborhood is home to one federal Superfund site, the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard … a sewage treatment plant that handles 80 percent of the city’s solid wastes, 100 brownfield sites [a brownfield is an abandoned, idled, or underused commercial facility where expansion or redevelopment is limited because of environmental contamination], 187 leaking underground fuel tanks, and more than 124 hazardous waste handlers regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.”

The shipyard, meanwhile, has been the central focus of controversy surrounding plans to clean up and redevelop the area. People Organized to Win Employment Rights (POWER) and Greenaction are currently challenging the EIR for Lennar’s massive redevelopment plan for the neighborhood, charging that the study is inadequate because a cleanup effort on the part of the U.S. Navy has yet to determine the level of toxicity that will need to be addressed, so the assessment is based on incomplete information. Asthma is commonplace in the Bayview, and health surveys have shown that the rates of cervical and breast cancer are twice as high as other places in the Bay Area.

“Our environmental issues are massive still, and it’s not just Bayview- Hunters Point,” notes Marie Harrison, a long-time organizer for Greenaction and a Bayview resident.

Harrison recalled the many times she’d gotten out of bed in the middle of the night to drive a friend’s or neighbor’s asthmatic child to the hospital. “That story has repeated itself tenfold in Richmond and in Oakland,” she added. Nor is the problem simply limited to those Bay Area cities, she said, noting that communities of color throughout the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 9 face similar issues.

As awareness about the scope of the problem has increased over the years, she said, “We start to say, my God, this triangle has to become a circle.”

Green days

news@sfbg.com

1892: The Sierra Club is established by John Muir and a group of professors from UC Berkeley and Stanford in San Francisco. In its first conservation campaign, the club leads efforts to defeat a proposed reduction in the boundaries of Yosemite National Park.

1902: After two years of intense lobbying and fundraising, the Sempervirens Club, the first land conservation organization on the west coast, is successful in establishing Big Basin Redwoods State Park — the first park established in California under the new state park system.

1910: The first municipally owned and operated street car service commences in San Francisco.

1918: Save the Redwoods League is established in San Francisco. A leader in proactive land conservation, SRL would go on to assist in the purchase of nearly 190,000 acres to protect redwoods and help develop more than 60 redwood parks and reserves that old these ancient trees in California.

1934: The East Bay Regional Park is established as the first regional park district in the nation. This radical Depression-era idea would much set the tone as the Bay Area land conservation vision expanded.

1934: The Marin Conservation League is founded by wealthy Republican women. Three years later, at the league’s behest, the Marin County Board of Supervisors adopts the first county zoning ordinance in the state in 1937. Over the next 10 years, the league helps create State Parks at Stinson Beach, Tomales Bay, Samuel P. Taylor, Angel Island, and expand Mt Tamalpais State Park.

1956: San Francisco activists, led in party by Sue Bierman, launch a campaign to stop a freeway that would have run through Golden Gate Park. It marks the first time city residents successfully block a freeway project and launches the urban environmental movement in America.

1958: Citizens for Regional Recreation and Parks is founded. It becomes People for Open Space in 1969 and morphs in 1987 into the Greenbelt Alliance. Their efforts lead to the creation of the Mid-Peninsula Open Space District in 1972 and Suisun Marsh in 1974.

1960: Sierra Club Executive Director David Brower launches a brand new organizing and educational concept, the exhibit format “coffee table” book series, with This Is the American Earth, featuring photos by Ansel Adams and Nancy Newhalland. These elegant coffee-table books introduced the Sierra Club to a wide audience. Fifty thousand copies are sold in the first four years, and by 1960 sales exceed $10 million. The environmental coffee table book emerged as part of a campaign to persuade Congress to enact the Wilderness Bill, legislation that would guarantee the permanence of the nation’s wild places.

1961: Save San Francisco Bay Association is founded by Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr and Ester Gulick to end unregulated filling of San Francisco Bay and to open up the Bay shoreline to public access.

1961: Pacific Gas and Electric Co. announces plans to build a nuclear power plant at Bodega Bay. Rancher Rose Gaffney, UC Berkeley professor Joe Neilands and others mount what will become the first citizen movement in the country to stop a nuclear plant. The Bodega Bay campaign marks the birth of the antinuclear movement.

1965: Responding to Bay Area citizens’ demands for protection of the bay’s natural environment, the California state legislature passes the McAteer-Petris Act, which establishes the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) and charges it with preparing a plan for the long-term use and protection of the Bay and with regulating development in and around it.

1965: Fred Rohe opens New Age Natural Foods on Stanyan Street in San Francisco. He goes on to open the first natural foods restaurant in 1967, Good Karma Cafe on Valencia Street. Rohe would go on to open the first natural foods distribution company in Northern California, New Age Distributing in San Jose in 1970 and found Organic Merchants (OM), the first natural foods retailer trade group.

1967: The Human Be-in is held Jan. 14 in Golden Gate Park (as a prelude to the Summer of Love) with as a major theme higher consciousness, ecological awareness, personal empowerment, cultural and political decentralization.

1967: Alan Chadwick comes to UC Santa Cruz and establishes the Student Garden Project and training program, which would train hundreds of today’s organic farmers.

1968: The Whole Earth Catalogue, published by the Point Foundation and edited by Stewart Brand out of Gate 5 Road in Sausalito is introduced, providing tools, philosophy, and reviews to the growing back-to-the-land movement, helping promote ecological living and culture alternative sustainable culture decades before those words became mainstream.

1969: Brower, after losing his job at the Sierra Club in part because of his opposition to the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, founds Friends of the Earth, the cutting edge activist group that would eventually have affiliates in 77 nations around the globe and become the world’s largest grassroots environmental network.

1970: Peninsula resident Neil Young writes and sings the lyrics “Look at Mother Nature on the Run in the 1970s.”

1970: Berkeley Ecology Center opens.

1971: Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund is established, marking the beginning of an explosion in environmental law.

1971: Alice Waters opens Chez Panisse, serving up California Cuisine and altering the Bay Area diet helping to create a market for local fresh organic fruits and vegetables. 1971: Berkeley resident Francis Moore Lappé publishes her best-selling book Diet for a Small Planet. Two million copies are sold and as the first book to expose the enormous waste built into U.S. grain-fed meat production, for her a symbol of a global food system creating hunger out of plenty; her effort alters millions of diets.

1971: San Francisco dressmaker Alvin Duskin launches a campaign to limit high-rise office development in San Francisco, creating new allies and a new coalition for urban environmentalism.

1972: The Trust for Public Land, a national, nonprofit land conservation organization that conserves land for people to enjoy as parks, gardens, historic sites, and rural lands, is founded by Huey Johnson, Doug Ferguson and Marty Rosen in San Francisco. TPL would go on to protect 2.8 million acres of land and is key in getting land trusts started in Napa, Sonoma, Marin, Big Sur, and around the state.

1972: The Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, first urban wildlife refuge in the United States, is established, encompassing 30,000 acres of open bay, salt pond, salt marsh, mudflat, upland and vernal pool habitats located in South Bay.

1972: The Save Our Shores campaign, developed in part by Bay Area residents, results in a state initiative, the Coastal Act of 1972, which is passed by the voters and establishes the first comprehensive coastal watershed policy in the nation.

1974: Berkeley Ecology Center starts the first curbside recycling approach in California, one of first such programs in the nation.

1974: The Farallones Institute in Berkeley begins building the first urban demonstration of an ecological living center with the Integral Urban House, a converted Victorian using solar and wind technologies, a composting toilet, extensive gardens, and energy and resource conservation features. It serves as an early model for the emerging Appropriate Technology Movement.

1975: Berkeley resident Ernest Callenbach self publishes Ecotopia after a round of rejections from New York publishers; it ultimately sells more than a million copies and becomes an environmental classic.

1975: San Francisco’s first community gardens are established at Fort Mason and elsewhere.

1975: The Marine Mammal Center, a nonprofit veterinary research hospital and educational center dedicated to the rescue and rehabilitation of ill and injured marine mammals, primarily elephant seals, harbor seals, and California sea lions, is established in the Marin Headlands.

1978: Raymond Dasmann and Peter Berg coin the term Bioregionalism in the publication of Reinhabiting a Separate Country, published by Berg’s Planet Drum Foundation in San Francisco. It represents a fresh, comprehensive way of defining and understanding the places where we live, and of living there sustainably and respectfully through ecological design.

1979 Greens Restaurant opens at Fort Mason in San Francisco and quickly establishes itself as a pioneer in promoting vegetarian cuisine in the United States.

1980: The Marin Agricultural Land Trust is established by Wetland Biologist Phyllis Faber and diary farmer Ellen Straus.

1980: Berkeley resident Richard Register coins the term “depave” — to undo the act of paving, to remove pavement so as to restore land to a more natural state. Depaving begins to spread to create many inner city urban gardening projects.

1981-82: Register and other activists, bring about the first urban day lighting of a creek in Berkeley’s Strawberry Creek Park where a 200-foot section of the creek is removed from a culvert beneath an empty lot and transformed into the centerpiece of a park.

1982: Earth First, a radical environmental group founded by Dave Foreman and Mike Roselle, sponsors the first demonstration against Burger King in San Francisco for using beef grown on land hacked out of rain forests. The demonstrations spread, turn in to a boycott, and after sales drop 12 percent, Burger King cancels $35 million worth of beef contracts in Central America and announces it will stop importing rainforest beef.

1983: Local residents Randy Hayes and Toby Mcleod release the documentary film The Four Corners, A National Sacrifice Area? , which conveys the cultural and ecological impacts of coal strip-mining, uranium mining, and oil shale development in Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona — homeland of the Hopi and Navajo. The film wins an Academy Award and illustrates serious environmental justice issues 10 years before that term is coined.

1985: The Rainforest Action Network, established in San Francisco, emerges from the Burger King action.

1986: Fifteen years after Duskin’s first anti-high-rise initiative efforts, San Francisco finally passes Prop. M, the nation’s most important sustainable growth law.

1988: Register invents a stencil to be used next to street storm drains that says “don’t dump — drains to bay.” The wastewater pollution mitigation education concept spreads around the region and nation and then becomes an international volunteer effort to lessen pollution in urban runoff, which generally flows untreated into creeks and saltwater.

1989: Carl Anthony, Karl Linn, and Brower establish the Urban Habitat Program in San Francisco, one of the first environmental justice organizations in the country.

1989: Laurie Mott of the National Resource Defense Council’s SF office rattles the apple industry by engineering a suspension of the use of the pesticide Alar by the Environmental Protection Agency. A national debate ensues.

1992: Berkeley writer Theodore Roszak coins both the term and field of ecopsychology in his book The Voice of the Earth. The movement he helps found asks if the planetary and the personal are pointing the way forward to some new basis for a sustainable economic and emotional life.

1992: The first Critical Mass bike ride (initially called a “Commute Clot”) is held in San Francisco. Similar rides, typically held on the last Friday of every month, began to take place in more than in over 300 cities around the world.

1993: The U.S. Green Building Council is founded by David Gottfriend in Oakland. The council becomes the most important environmental trade organization in the world. In 1998, the council develops the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Green Building Rating System, which provides a suite of standards for environmentally sustainable construction and design.

1995: The Edible Schoolyard is established by Chez Panisse Foundation at Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School in Berkeley. It serves as a model for similar programs in New Orleans and Brooklyn, and inspires garden programs at other schools across the country.

1999: The Green Resource Center starts as a joint project of the City of Berkeley, the Northern California Chapter of Architects, Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), and the Sustainable Business Alliance.

2000: Wendy Kallins, working with the Marin Bicycle Coalition, begins a Safe Route to Schools program in Marin to encourage students to walk or bicycle to school. The program is so successful that Congress allocates more than $600 million for similar efforts across the country.

2001: The first Green Festival is held in San Francisco.

2001: Berkeley becomes first city in nation with curbside recycling trucks powered by recycled vegetable oil, thanks to a campaign by the Berkeley Ecology Center.

2002: San Francisco adopts a greenhouse gas reduction initiative that aims to reduce the city’s greenhouse gas emissions to 20 percent below 1990 levels by 2012.

2003: Bay Area Build It Green is formed by a number of local and regionally focused public agencies, building industry professionals, manufactures, and suppliers. Its activities are focused on increasing the supply of green homes, raising consumer awareness about the benefits of building green, and providing Bay Area consumers and residential building industry professionals a trusted source of information.

2005: San Francisco passes the Precautionary Principle Purchasing Ordinance, which requires the city to weigh the environmental and health costs of its $600 million in annual purchases — for everything from cleaning

supplies to computers.

2006: Bay Localize is launched in the East Bay with the aim to work to build a cooperative, inclusive movement toward regional self-reliance and increase community livability and local resilience for all while decreasing fossil fuel use.

2007: In an effort to meet the challenges of global warming, carbon pollution and job creation, East Bay activist Van Jones declares that the nation is going to have to weatherize millions of homes and install millions of solar panels. His best-selling book, The Green Collar Economy, stimulates a national movement and a new organization, Green For All.

2007: San Francisco begins collecting fats, oils and grease from residential and commercial kitchens, for free, to recycle into biofuel for the city’s municipal vehicles, the largest biofuel-powered municipal fleet in the United States.

2008: San Francisco becomes the first U.S. city to establish green building standards.

2010: The Green Building Opportunity Index names San Francisco and Oakland the top two cities in the nation for green buildings.

2010: San Francisco becomes home to the Sunset Reservoir Solar Project, the largest solar-powered municipal installation in California.

Fishing for plastic

sarah@sfbg.com

GREEN ISSUE For the past two summers, scientists and environmentalists with Project Kaisei, a Sausalito nonprofit focused on increasing public awareness of marine debris, have sailed out under the Golden Gate Bridge to survey trash in the North Pacific gyre.

A gyre is a naturally occurring system of rotating currents in the ocean that is normally avoided by sailors because of its light winds. The North Pacific Gyre is the largest of the five major oceanic gyres in the world, and the one with the biggest known accumulation of trash, most of which is plastic. Some folks call this vortex the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. But Project Kaisei founder Mary Crowley calls the vortex “the eighth continent” to convey its size and impact.

Now, as Project Kaisei prepares for its 2011 expedition, which will likely take place in June — depending on funding, marine conditions, and equipment collection — team members are taking the next steps in the project’s mission to capture the plastic in the gyre. These steps include testing for efficient ways to clean up trash mid-ocean and exploring if some captured plastic can be turned into liquid fuel to power future clean-ups.

“We’ll be focusing on testing marine debris collection equipment, doing some clean-up, further recording what’s out there, and working with ocean current experts. But we need good sponsorship,” Crowley said. “Down the line, we’re looking to have a recycling plant on deck with smaller vessels feeding it so we can do clean-ups mid-ocean. And we’re going to recycle. It’s not going to end up in a dump with plastic blowing back into the ocean.”

Crowley believes unemployed fishermen should be paid to clean up the gyres. “And we should start in our own towns and states and countries,” she said. “We need to produce a solution locally to take effect globally. Part of the response has to come from multinational corporations that are selling stuff throughout world. It’s shocking to me that 90 percent of our pelagic fish are gone and we’ve killed 50 percent of the corral reefs.”

Project Kaisei’s preparations are taking place in the wake of a tsunami that devastated Japan in March, sucking a big pulse of debris into the ocean and crippling four nuclear reactors that continue to leak radiation into the water, raising fears of damage to sea life.

Experts predict that some of the debris from the tsunami will eventually wash up on beaches in Hawaii and California, but Crowley doubts the state will be affected radiologically. “The majority [of the debris] got whooshed out by the tsunami before the leaks began,” she explained.

She says that at a marine debris conference in Honolulu shortly after the tsunami, attendees expressed concern about “land-sourced” debris — trash that flows into the ocean by way of rivers and streams or is dumped directly into the ocean from ships.

“People said that in recent years there’s also been all this debris from natural disasters, including tsunamis,” Crowley noted. “Well, I see debris from natural disasters as all the more reason to develop effective ways to get trash out of the ocean.”

But Captain Charles Moore, who founded the Algalita Marine Research Foundation in 1994 to restore disappearing kelp forests and wetlands along the California coast, thinks a moratorium on plastic production would make the most sense.

Moore’s focus shifted in 1997, when he encountered trash, mostly plastic, scattered across the North Pacific Gyre, and subsequent studies by his foundation claim that trash outweighs zooplankton in the gyre by a factor of six to one.

“Mary Crowley really wants to go out there with big boats and get big pieces of plastic out,” Moore said. “I’m not really opposed to that, but it’s a lot of time and money that could be spent trying to stop the waste getting there in the first place. It’s like having a leaking faucet and bailing out the sink rather than calling the plumber. The time has come for society to draw a line in the sand and say no more plastic. Our plastic footprint is causing more problems than our carbon footprint.”

Moore believes it’s time to withdraw from globalized production and support locavore and slow-food movements instead. “We send stuff to be produced in the cheapest locations possible, package it in plastic, then send it back here. It’s nuts,” he said.

But Crowley says not all plastic use is bad, even as she advocates for getting larger pieces of plastic out of the water, and supporting companies that use less on no packaging.

“Plastic is an amazing material for construction and railroad ties, decking, and some medical uses,” she said. “It’s just not right material for throw-away items because it lasts for centuries. I subscribe to oceanographer Sylvia Earle’s view that a plastic bottle can last for 500 to 600 years. That’s why it’s important to get out these bigger pieces of plastic. We don’t want them broken down in the belly of a whale or the stomach of an albatross.”

Studies suggest that 100,000 marine mammals — possibly more — along with thousands of sea birds die each year from debris entanglement, and that thousands more marine mammals, sea birds, fish and sea turtles die from ingesting marine debris, including plastic bags, which bear an unfortunate resemblance to jellyfish, once in water.

Crowley recalls how in 2009, when Project Kaisei had 25 people on board, including scientists, sailors, filmmakers, graduate students, and engineers, the team was surprised to find plastic in sampling taken 400 miles off the West Coast.

“We were anticipating clean water,” Crowley said. In the end, the project’s research vessel, the Kaisei, whose name means “ocean star” in Japanese, and the New Horizon, a Scripps Institute vessel that participated in the project’s first mission, found some plastic in every single trawl.

“A lot was smaller microparticulates of plastics and preproduction plastic pellets,” Crowley said, noting that she also saw Clorox bottles, plastic bags, ghost nets, toothbrushes, children’s toys, and plastic chairs floating on, or lurking up to nine feet below the surface of the ocean.

“If you’re in still water, you sometimes see confetti-like pieces of plastic. And if you’re up on the crow’s nest and going two to three knots, you see bigger pieces,” she said.

No one knows exactly how many bits of debris are already floating in the ocean or have been ground up into tiny particles on our beaches. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration notes that, to date, “there has not been a comprehensive marine debris abundance assessment for the world‘s oceans, or even for a single ocean.“

Moore‘s foundation says 80 percent of marine debris comes from land and only 20 percent from marine-related activities like fishing. To Crowley‘s mind, the main problem is that only 5 percent to 7 percent of plastics are recycled.

“Plastic was invented in the 1880s to replace ivory for pool balls and didn’t proliferate until the last 60 years,” she said. “But even when plastic is dumped into a landfill, it has this insidious way of blowing about and ending up in drains, rivers, and oceans because plastic is a very light, easy material to move around.”

Crowley grew up sailing on Lake Michigan, ran away to sea at age 19, and ended up sailing around the world and founding an international boat chartering business. Somewhere along the line, she says, she started describing the vast, continuous expanse of water that covers 71 percent of the planet and creates most of our air as “the global ocean.”

“It really is all connected,” she said. “The health of the oceanic ecosystem is very important to the health of the planet. There’s a terrible misconception that the oceans are so vast they can be used as a garbage pail.”

When she began to see trash underwater, Crowley realized that future generations wouldn’t be able to enjoy the oceans the way she has. She decided to take action four years ago when she began to see an increase in the garbage covering the North Pacific Gyre.

“I kept seeing the message that there’s a terrible problem, but there’s nothing we can do,” Crowley said, recalling how that messaging and her own sense of urgency prompted her to found Project Kaisei to increase public understanding of what’s in the gyre.

“If you’re in the area for a couple of weeks, you have days when you feel you’re voyaging through a field of scattered garbage,” she said. “And when you look out, you see garbage on the horizon.”

Desperately seeking squash bees

UPDATE! In the print version of this article, this reporter inadvertently described Anthidium maculosum as a territorial leafcutter bee. It is in fact a wool carder bee. My humble apologies to the bees and the experts who helped identify them.

Sarah@sfbg.com

GREEN This summer, I hunted squash bees. The hunt began on a sunny mid-July afternoon at the home of Celeste Ets-Hokin, an advocate for native bees who lives in Oakland and has just published a 2011 calendar on the importance of conserving bee habitats.

As Ets-Hokin explains in the forward of her calendar (available from the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation), “Most of our fruit, vegetable, and seed crops depend on bees for pollination. For bees, success depends on habitat, habitat, habitat.”

Ets-Hokin has planted her own backyard, on a sunny ridge near Lake Merritt, with lavender, basil, and other bee-attracting plants. Although her yard was abuzz in midsummer with the sound of honey, bumble, carpenter, leafcutter, longhorn, and green metallic sweat bees, there was no sign of squash bees.

That’s because squash bees only visit the blossoms of squash plants and other members of the gourd family, which Ets-Hokin doesn’t grow in her yard.

So we decided to head for the trials garden next to Lake Merritt, which is funded by the University of California and the Alameda County master gardeners program.

Ets-Hokin spent the last 18 months creating a bee-attracting zone in this garden. And now she hoped to find squash bees in the garden’s vegetable patch, where squash and other vegetables are tested for suitability to the local environment.

Clad in just shorts and T-shirt, Ets-Hokin looked rather vulnerable, considering she was about to go bee hunting. But, as she explained, there was no imminent threat of stings: female bees only sting those who threaten their nest, and male bees have no stingers.

“Male squash bees live to drink (nectar) and have sex with female squash bees,” Ets-Hokin joked, as Rollin Coville, a lanky entomologist who has photographed insects for three decades, joined the squash bee hunt.

Dressed in a hat, slacks, and vest and hauling a state-of-the art camera, Coville was hoping to get shots of the elusive male squash bees, which emerge in late summer and can sometimes be found taking naps in the squash blossoms in the afternoon.

Last year Ets-Hokin produced a 2010 native bee calendar highlighting Coville’s kickass images and informative sidebars on how to attract these native pollinators to urban yards.

This year she focused on the importance of bee habitat on farms in face of proposed food safety regulations that could undermine existing federal bee conservation programs. And she hoped to use Coville’s squash bee photographs as her August 2011 pin-up shot.

But before we could escape Ets-Hokin’s yard, Coville quickly withdrew a clear vial from his vest pocket, popped it over a bee on a nearby flower, then corked the vial.

The bee began to buzz furiously.

“I think it’s a Anthidium maculosum,” Coville declared as he uncorked the vial and let what turned out to be a territorial wool carder bee go back to its business of guarding nectar in a nearby plant.

We eventually reached the trial gardens, where Coville showed me how to pry open the fleshy yellow squash flowers that lie half-hidden below the plant’s massive prickly leaves atop budding zucchini that threaten to grow as big as canoes if left unpicked.

The first dozen squash blossoms were vacant, save for a few ants and beetles, and Coville wondered aloud if late rains and a cold snap had decimated bee populations.

But then I found a squash bee sitting inside a flower like a king on a bright yellow throne. And at the next flower, six squash bees were gently napping inside.

As I tried to hold the fleshy flower petals open so Coville could photograph these sleepy males, one petal began to vibrate loudly. I let go and a male bee unwrapped itself from the petal and zoomed away into the undergrowth.

At the end of the afternoon when I thanked Ets-Hokin for inviting me on the bee hunt, she turned to Coville and laughed, “I told you she was easily entertained.”

For information about native bees, visit www.xerces.org/pollinator-resource-center.

Complicating the simple

steve@sfbg.com

GREEN CITY San Francisco can legally give more street space to bicycles, even if it delays cars or Muni in some spots, a policy that enjoys universal support among elected officials here. So why have all the city’s proposed bike projects been held up by an unprecedented four-year court injunction, despite the judge’s clear affirmation of the city’s right to approve its current Bicycle Plan as written?

The answer involves a mind-numbing journey into the complex strictures of the California Environmental Quality Act and its related case law, which was the subject of a three-hour hearing before Superior Court Judge Peter Busch on June 22 that delved deeply into transportation engineering minutiae but did little to indicate when the city might be able to finally stripe the 45 bike lanes that have been studied, approved, funded, and are ready to go.

Anti-bike activist Rob Anderson and attorney Mary Miles have been on a long and lonely — but so far, quite successful — legal crusade to kill any proposed bike projects that remove parking spaces or cause traffic delays. They have argued that the city shouldn’t be allowed to hurt the majority of road users to help the minority who ride bikes, urging the city and court to remove those projects from the Bike Plan.

But Busch repeatedly said the court can’t do that. “That’s the policy question that’s not for the court to decide,” he told Miles in court, later adding: “I don’t get to decide that the Board of Supervisors’ policy is misguided.”

Yet city officials have offered detailed arguments that the policy of facilitating safe bicycling isn’t misguided, but instead is consistent with the transit-first policy in the city charter and with the goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving public health, and even alleviating overall traffic congestion by giving more people good alternatives to driving a car.

Busch hasn’t indicated that he has any issues with that rationale. Instead, the question is whether policymakers had enough information — in the proper manner spelled out by two generations’ worth of legal battles over land use decisions in California — to make their unanimous decisions to approve the Bike Plan in 2005 and again in 2009, after completing a court-ordered, four-volume, two-year, $2 million environmental impact report.

Miles argues that the EIR is legally inadequate in every way possible, employing such gross hyperbole in condemning it as a hollow document that does nothing to explain or justify any of its conclusions that Busch told her at one point, “That’s such an over-argument, it leaves me wondering about the rest of your argument.”

But he’s certainly considering the rest of her argument that more analysis was required, going into great detail on the questions of whether the city studied and spelled out enough alternatives and mitigation measures, how much of the voluminous traffic survey data should be in the plan, whether there was enough support for the thresholds of significant impacts, and what the remedy should be if he finds some minor errors in the methodology.

Yet even Busch said there wasn’t a clear regulatory road map for the city to follow on this project. “There probably has never been an EIR for a project like this,” he acknowledged. It was the city’s decision in 2004 to do a Bike Plan that mentioned specific projects without studying them that led to the injunction and this extraordinarily complex EIR, which did detailed analysis on more than 60 projects.

“Once you get that complexity, the toeholds are everywhere to fight it,” activist Mark Salomon, who has long criticized city officials and bicycle activists for their approach to the Bike Plan, told us.

But Kate Stacey, who heads the land use team in the City Attorney’s Office, says the city will be in a good position to quickly create lots of bike lanes once this plan passes legal muster.

“The city can now go through the specific bike projects without having another step of analysis,” she told us. “I think it’s a complete and elegant approach even if it was more time-consuming at the outset.” Busch asked both sides to submit proposed orders by July 6 and responses to those orders by July 13, with a ruling and possible lifting of the injunction expected later this summer.

From freeway to favas

Perhaps you’ve noticed a fresh mountain of fava beans arising along Octavia Boulevard as you travel toward Market Street, in the spot where a freeway used to touch down. Don Wiepert certainly has. He’s a senior citizen who lives across the street from the rows of green sprouts, and even helped to raise the crop in his own living room.

Wiepert is one of 1,500 neighborhood volunteers who have taken part in the birth of Hayes Valley Farm, an exciting experiment in participatory urban agriculture. Started in January by three young permaculture activists, the project has converted into farmland a city block whose previous harvests were auto exhaust from the freeway on-ramp, and most recently, crime and vagrancy.

Farm organizer Jay Rosenberg explains the process as we tour the fields he helped to envision. Back in 1964, neighborhood activists from Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association and other groups organized to stop the progress of the Central Freeway that would connect Highway 101 to the Golden Gate Bridge. The show of community force was impressive, but it stranded the planned highway on- and off-ramps on a block of land between Octavia and Laguna streets. “They left them here standing like ruins,” Rosenberg said. “This was a 2.2-acre forgotten space.”

“It was a place for homeless living,” Wiepert said on a recent trip to the farm’s biweekly work party, while volunteers and a handful of paid staff buzzed about replanting seedlings and erecting a homemade greenhouse. “It was fenced off, ugly, inaccessible.” He looks around. Not to resort to a cliché, but there’s a discernible twinkle in his eyes as he says, “Now it’s wonderful.”

Although the block was in a desirable central location, its soil had been damaged from years of exposure to car emissions, which can leave behind lead and other heavy metals. But the team behind Hayes Valley Farm has a plan. The ivy that threatened to strangle the farm’s trees has been stripped, piled into heaps that are covered with cardboard and horse manure to begin a turbo-fertilization process that mimics what happens on forest floors. Once this new soil has been created, it is spread and implanted with fava seedlings, which were selected for their nitrogen-producing capabilities.

Rosenberg halts his tour of the process to pluck a bean plant from the ground and finger the white nitrogen nodule its roots have produced. “Look how well they’re doing,” he says over the nascent crop, proud as a papa. Once these plants are mature, half will be harvested as food, and half chopped at the root to speed the release of their nitrogen into the rest of the soil. Already young lettuces peek beneath the rows of beans, signs that the farm is ready to experiment with other foods.

San Francisco is a weather system unto itself, rendering the city’s ideal crops the subject of much conjecture. “This is a cool, Mediterranean-like, foggy desert,” Rosenberg says. “We’re doing lots of research on species that do well here, which will be knowledge the public can use.” The farm, like the Alameda County Master Gardeners (www.mastergardeners.org) who run a similar program, is serving as a test arena to see what urban gardeners can reasonably expect to thrive here.

The farm is now home to 1,500 plants, including 150 fruit trees, most sitting in pots on the old freeway on-ramp in what Rosenberg calls “the biggest patio garden in San Francisco.” So far, all the crops have gone into the bellies of the volunteers who raised them, putting in more than 4,000 person-hours during the four months the farm has been open.

But it’s not just the free groceries that keep neighbors returning to Hayes Valley Farm. In addition to the work parties, the site has been home to popular screenings of environmentally-themed films and a locus of outdoor learning. One group of students from the Crissy Field Center painted a mural for the farm that will soon occupy one wall of its planned on-site classroom. A weekly yoga class is planned, as are daily tours for farm newbies interested in learning more about the planting going on down the street.

In a time of uncertainty about what we’re supposed to eat, people are finding something to be sure about here. “I appreciate the opportunity to hang out with the younger people and their energy,” Wiepert says, moments before flinging a stick for one of the farm’s part-time dogs to chase after. “I think this place facilitates a feeling for a lot of people that they’re doing something meaningful.” *

HAYES VALLEY FARM

450 Laguna, SF

(415) 763-7645

Loving LaHood

By Jobert Poblete

news@sbg.com

GREEN CITY U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood wowed urban cycling advocates at the National Bike Summit in Washington, D.C., in March when he climbed atop a table to praise them for their work promoting livable, bike-friendly communities. LaHood followed up that connection with a blog post in which he announced a "sea change" in federal policy, declaring: "This is the end of favoring motorized transportation at the expense of nonmotorized."

The groundbreaking post was accompanied by a DOT policy statement urging local governments and transportation agencies to treat walking and bicycling as equal to other modes of transportation. The statement concluded that "increased commitment to and investment in bicycle facilities and walking networks can help meet goals for cleaner, healthier air; less congested roadways; and more livable, safe, cost-efficient communities."

Since then, LaHood has come under fire for his pro-bike statements. The National Association of Manufacturers’ blog said that the policy would result in "economic catastrophe." At a House hearing, a representative implied that the secretary was on drugs.

But bike advocates, who were initially wary of having this key post occupied by one of the few Republicans in the Obama administration, have rallied to LaHood’s defense. In San Francisco, bike and livability advocates are optimistic that LaHood’s statements will be backed up with meaningful action.

"LaHood is not just talking the talk," San Francisco Bicycle Coalition program director Andy Thornley told the Guardian. "He seems to be actively moving federal transportation policy toward a broader, more sustainable program."

As DOT secretary, LaHood has enormous influence on how federal money is spent and on the Obama administration’s transportation policies. Thornley is hopeful the new policy direction will free more money for bikeways and other alternatives to the automobile. The federal government doles out billions of dollars for transportation, and beyond some direct funding of bike and transit projects, removing conditions that have forced recipients of federal transportation dollars to spend it on roads and highways could have a big impact on bike and pedestrian-friendly regions like the Bay Area.

"We’re already doing a good job regionally of prioritizing how we spend our money," Thornley said. "But on the federal end, the money comes out already conditioned and has to be spent on highways."

Tom Radulovich, executive director of Livable City, echoed Thornley’s enthusiasm for the DOT’s new policy direction. "If livable, walkable communities become a priority of the federal government, that could be really revolutionary," he said.

But Radulovich acknowledged that much of this depends on the outcome of a new surface transportation bill being drafted in Congress. The bill would allocate hundreds of billions in federal transportation dollars, and bike and transit advocates are already mobilizing to make sure it’s written in a way that promotes livability and sustainability. Transportation for America, a national coalition that includes a number of Bay Area groups, is lobbying Congress and the Obama administration to create a "21st century transportation system" that supports walking, biking, and sustainable development.

To succeed, advocates will have to overcome a number of other challenges. Thornley pointed out that outside of urban centers like the Bay Area and Seattle, bikes aren’t taken seriously as a form of transportation. He also warned that the industries that benefit from automobiles will be pushing back and telling the public that more bikes and transit will cost their industries jobs.

But Thornley is hopeful that other industries are getting the message that sustainable development is good for business. He said people are returning to cities and developers are taking note. "Developers are casting positive votes by investing in the city, building up residential options, and recognizing that the market wants these choices."

If new bike-friendly and pro-livability policies are to gain traction, Thornley said, "it will be about showing folks that spending money on transit, biking, and walking is just as productive for jobs and building communities. In the long run, it’s a much better investment."

Court to Chevron: consider climate change

By Adam Lesser

news@sfbg.com

GREEN CITY When a California appellate court rejected Chevron Corporation’s attempt to expand its Richmond refinery without clarifying whether it intends to process heavier, more polluting crude oil two weeks ago, planetary concerns loomed even larger than local impacts.

Environmental and local groups celebrated a ruling against a project that would have fouled Bay Area air, but legal experts have pointed out that the long-term impact of the ruling may have less to do with crude oil refining and more to do with global warming.

Justice Ignacio John Ruvolo took nine pages of the 35-page decision specifically to address the fact that the environmental impact report (EIR) failed to outline how Chevron was going to mitigate the approximately 898,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions the refinery expansion would create. The Richmond refinery is already the largest emitter of CO2 in California, clocking in at just under 4.8 million metric tons annually.

The appellate court’s ruling is the first to state that it is illegal under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to defer to a later date the mitigation of greenhouse gases. Ruvolo, representing the 3-0 ruling, wrote “incremental increases in greenhouse gases would result in significant adverse impacts to global warming, the EIR was now legally required to describe, evaluate, and ultimately adopt feasible mitigation measures that would ‘mitigate or avoid’ those impacts.”

Ruvolo goes on to point out that if the greenhouse gas mitigation is worked out later, the public wouldn’t have a chance to comment on how best to offset those emissions. Or worse: maybe adequate mitigation isn’t even possible. An amicus brief filed by the Center for Biological Diversity pointed out that mitigating 898,000 tons of greenhouse gases is equivalent to taking 160,000 cars off the road. That’s a tall order, and the appellate court wants a better EIR that lays out adequate measures to offset the added emissions.

“There was absolutely no specificity on whether the mitigation could be accomplished,” said Matt Vespa, who wrote the amicus brief. “There needs to be a clear road map of what will happen.”

Possible mitigation measures include internal efficiencies at the refinery, ranging from improved heat exchangers to carbon sequestration. But Vespa and Earthjustice attorney Will Rostov, who argued the case, are hopeful that a plan could include measures that would aid the Richmond community, such as retrofitting low income homes or installing clean sources of energy like solar panels.

The issue of mitigating greenhouse gases comes as Democrats in the U.S. Senate prepare to introduce a cap-and-trade bill. Rostov expressed concern that mitigation could occur far away from Richmond, where residents could suffer environmental harm and receive no benefits from Chevron.

Chevron has not yet said what its plans are, only that it is reviewing its options. They include cooperating with a new EIR, halting the expansion, or appealing the ruling to the California Supreme Court. On the possibility of appealing, Vespa commented, “I certainly don’t think the decision was a stretch in terms of the law.”

For now, the community waits. Richmond has a 19 percent unemployment rate and there have been mixed reactions to the project ever since a Contra Costa Superior Court halted the expansion last summer. The project had support from trade unions in need of jobs, although many residents are fearful of more pollution from a corporation it views as a bad and untrustworthy neighbor.

The political fight between the city and Chevron got worse this year as a battle over how much utility tax Chevron should pay became irresolvable. The situation is heading for a showdown in November, with both sides authoring competing ballot measures and the potential for the city to lose $10 million in revenue. A proposed 15-year agreement recently has been outlined.

The conflict over taxes is another milestone in a difficult relationship between Chevron and the citizens of Richmond. The near-term victory for those living in Richmond is a legal framework for holding Chevron responsible for pollutants it puts in the air Richmond citizens breathe.

“CEQA has been around for 40 years and it’s been protecting air and water,” Rostov told the Guardian. “This case shows that CEQA is going to protect the public health from greenhouse gases.”

Dude, where’s my car share?

By Brady Welch

news@sfbg.com

GREEN CITY Owning and storing a car in San Francisco is neither cheap nor efficient, so car-sharing companies have become increasingly popular in recent years. So why can’t individual car owners share or rent their vehicles? Right now, insurance law makes that difficult, but new legislation could make it easier for people to share their cars.

California Assembly Member Dave Jones (D-Sacramento), a candidate for Insurance Commissioner, unveiled the legislation during an April 28 press conference in San Francisco. Flanked by City CarShare CEO Rick Hutchinson and Sunil Paul, chief of a car-sharing start-up called Spride, Jones outlined legislation that would allow car owners to rent their vehicles to car-sharing organizations without risk of losing their individual auto insurance. Think of the idea as a more decentralized — but not quite DIY, at least not yet — version of other successful car-sharing organizations.