news@sfbg.com

California voters are about to be bombarded by more than $50 million in political advertising designed to convince them to approve a pair of measures desperately sought by two powerful corporations with a long history of lies and political corruption.

Will this brazen and transparently self-serving effort work? And what does it say about the state of modern politics — particularly California’s money-driven initiative system — that these deceptive campaigns just might convince voters to cast ballots against their own interests?

The corporations have every incentive to try to buy the election — and if they win, it could encourage others to follow. By spending tens of millions of dollars on a campaign today, they will potentially save and earn many times that over the long run. It’s a business decision, plain and simple.

If Pacific Gas & Electric Co. can pass Proposition 16, which requires a two-thirds vote for any municipalities to do renewable energy projects and deliver that power directly to consumers, that will kill the chances of government-backed rivals popping up to compete. It will save the company the tens of millions of dollars it regularly spends to defeat public power campaigns across the state.

If Mercury Insurance is successful with Proposition 17, which overturns part of the landmark insurance reform measure Prop. 103 and would allow companies to increase the car insurance premiums for new drivers and those whose coverage has lapsed, a company notorious for mistreating customers and defying regulators will be able to greatly increase its market share and profits.

Both measures are strongly opposed by legitimate consumer rights groups, public interest advocates, and almost all of San Francisco’s elected officials. But both corporations have proven to be unusually effective over the years at using lavish spending — with money extracted from consumers — to convince private groups and public officials from both major parties to do their bidding.

And plenty of public officials who ought to be opposing the measures are either on the wrong side or silent.

Will Mercury-backed Californians for Fair Auto Insurance Rates (which calls itself Cal-FAIR) be able to convince voters that Prop. 17 is really about saving drivers money? And will PG&E-financed Californians to Protect our Right to Vote succeed in making the case that supermajority thresholds are a needed safeguard against the electricity schemes of elected officials?

That all depends on how informed voters are when they cast their ballots.

MERCURY RISING

Mercury Insurance founder and chairman George Joseph became a billionaire by offering car insurance policies to California drivers who were at a higher risk for accidents than most other companies would accept, charging them expensive rates and then challenging their claims.

When Forbes magazine named Joseph the 283rd richest American in 2005, with an estimated worth of $1.2 billion, it wrote laudably about the practice in describing him: “Numbers guru earned Harvard math and physics degree in three years. Began as actuarial trainee at Occidental Life for $225 a month, quit after realizing salesmen made more. Created own property and casualty insurance company. The Mercury General 1962: targeted customers having trouble getting auto insurance; aggressively investigated suspicious claims. Took public 1985.”

Mercury currently has about $2.3 billion in market capital and a stock price that has roughly doubled in the year since the company began funding a $3.5 million signature-gathering effort to place Prop. 17 on the June ballot. That may be a coincidence, but it’s certainly true that Mercury’s fortunes are tied up with California motorists.

The company’s most recent annual report, filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission last month, shows California car insurance policies are the lion’s share of the company’s business. Almost 80 percent of its premiums are in California (followed by Florida, Texas, and New Jersey), and 83.2 percent of its $2.6 billion in total premiums cover private passenger cars (as opposed to commercial auto, homeowners, and other insurance products). In California, 81 percent of Mercury customers earned “good driver” discounts, while 19 percent are in higher-risk categories, paying much higher monthly premiums.

California’s car insurance regulation system was created almost entirely by the 1988 pro-consumer ballot measure Prop. 103. That initiative established a system of regulatory oversight and financial transparency, cutting premiums by about 20 percent and limiting what companies could consider when assigning rates.

The main rating factors, in descending order of importance, are customers’ driving safety records, number of miles they drive each year, and the number of years they have been driving — which all have a direct relationship to the odds of having an accident.

Before Prop. 103 went into effect in 1990, insurance companies could pretty much charge whatever they wanted, based on whatever criteria they saw fit. And that freedom became a gold mine in 1984 when the California Legislature required all drivers to have car insurance.

“After that, everyone in the marketplace is required to buy insurance and there’s no protection against how much insurance companies could charge you for it, or even if they refused to sell it to you because of where you lived or the color of your skin. There were just no protections,” said Harvey Rosenfield, founder of Consumer Watchdog.

So Rosenfield wrote Prop. 103 and he’s been battling Mercury Insurance ever since. They’ve tangled in the halls of the Legislature, where politicians from both major parties have received millions of dollars in campaign contributions to push bills to undermine Prop. 103. They’ve fought in court in countless hearings over more than two decades, most recently on March 12 in a dispute over Prop. 17 ballot language and arguments. And they’ve fought in the court of public opinion, right up to today, as Rosenfield leads the fight to defeat Prop. 17.

“One of the most pernicious practices after the Legislature said you have to buy insurance was that when you went to the insurance companies and said, ‘OK, I’m required by law to buy insurance, now sell it to me.’ They’d say, well you didn’t have it before, so we’re not going to sell it to you now. Or, you didn’t have it before so therefore we’re going to surcharge you and double the price of insurance. Talk about a Catch 22,” Rosenfield said.

Rosenfield and other consumer advocates appealed to legislators, but, he said, “Of course, the Legislature was too beholden to the insurance lobbyists to do any of the proposals that we were offering, so we went to the ballot box in 1988.” And despite an $80 million campaign financed by the insurance industry, Rosenfield’s group won — sort of.

“No longer would your ZIP code be the dominant determinant for how much you pay,” Rosenfield said. But the struggle to implement the law continued. “That battle, just to get that put it in place, we didn’t win that until 20 years after [Prop.] 103 began. We won basically in 2006, 18 years later, after court challenges and going to the [insurance] commissioner.”

INSURANCE POLITICS

Mercury was one of the major industry players challenging Prop. 103 in court. The company also deftly worked the political system, most scandalously through former Senate President Pro Tem Don Perata, a Democrat now running for mayor of Oakland. Mercury not only gave extensive political contributions to Perata, who then carried legislation for Mercury, including a bill to basically do what Prop. 17 would do, but a San Francisco Chronicle investigation in 2004 found that Mercury’s cash allegedly went into Perata’s personal account in a money-laundering scheme that reportedly triggered an FBI investigation and raid on Perata’s house (no charges were ultimately filed).

Rosenfield described how the company operates in the political arena: “Mercury realizes it’s going to lose the civil suit, goes to Sacramento, spreads a fortune in campaign contributions, and lo and behold, gets a bill passed overriding this provision of Prop. 103, legalizing its surcharges. [Gov. Gray] Davis vetoes it in 2002 on the grounds it violates Prop. 103. Another year goes by, Mercury spreads even more money around, and this time Davis is in a recall election and needs Mercury’s money. So he takes the money — it’s $100,000 or more — and Davis signs the bill. We have to go to court and challenge the bill as an unconstitutional amendment to Proposition 103, which we finally succeed in doing and it’s upheld by the Court of Appeals in 2005. All that time, Mercury is overcharging people. Ultimately, Mercury is told that the law you sponsored is invalid and you can’t do it anymore, so it stops in 2005 — 10 years of wanton, brazen violation of the law. And that brings us to the Mercury initiative.”

Joseph refused to talk to us (he grants almost no press interviews) and Mercury spokesperson Coby King referred questions to Kathy Fairbanks, who heads the Mercury-sponsored Cal-FAIR.

But when we noted that this group is supposedly independent of Mercury, and that my questions were about the company’s history of hostility to Prop. 103, King finally made this comment: “Prop. 103 is the law of the land, but to the extent there are improvements that can be made that are pro-business and pro-consumer, Mercury has not been shy about acting in the public interest.”

POWER PLAYS

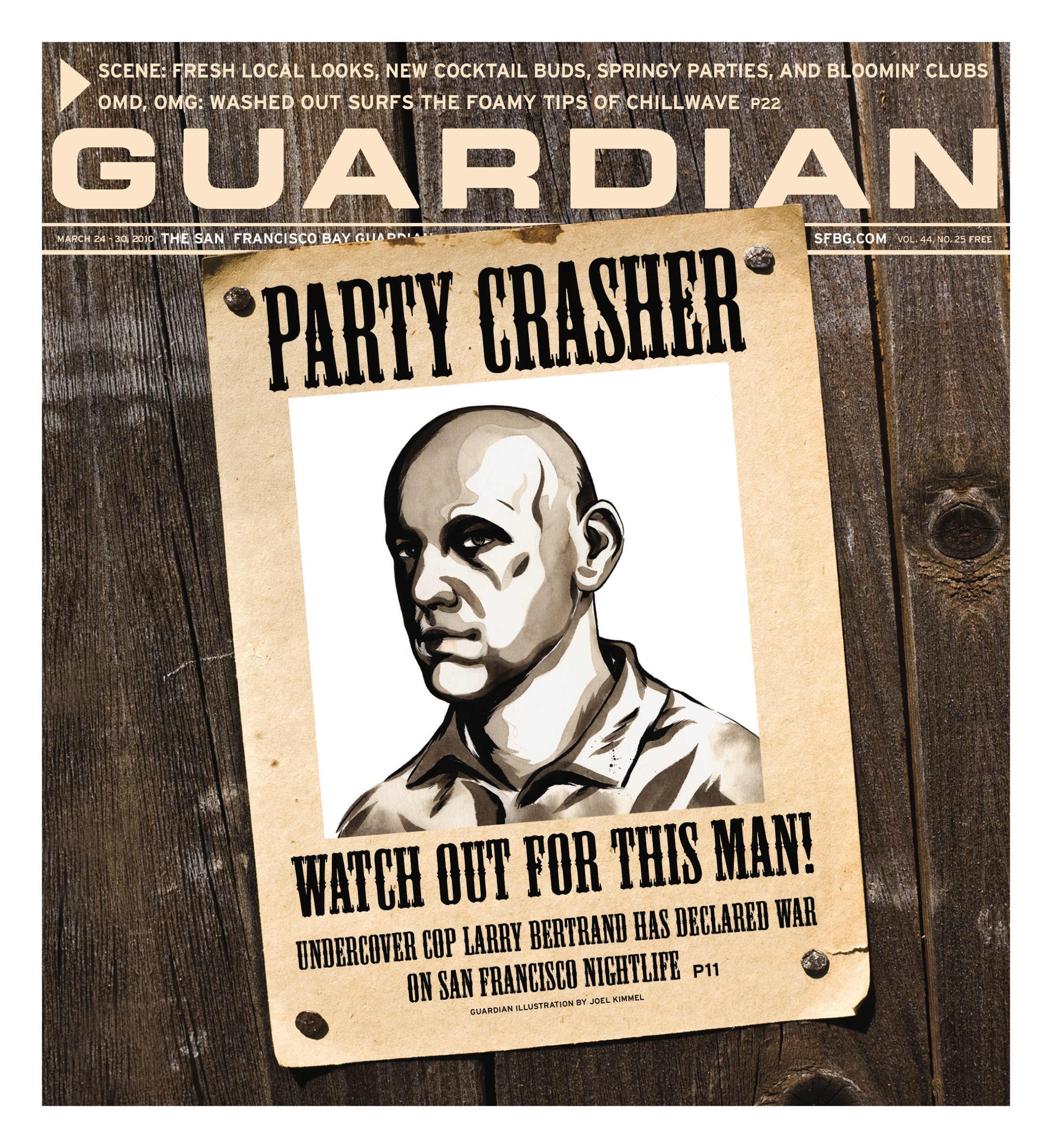

Another corporation that has not been shy about flexing its muscle in the political arena is SF-based PG&E, California’s largest and most influential utility company. It is single-handedly bankrolling the Yes on 16 Campaign. Dubbed the “Taxpayers Right to Vote Act,” Prop. 16 was crafted by a Sacramento public relations outfit and law firm that have long histories with PG&E. Its goal: end the expansion of public power in California.

The utility has amassed a war chest of funding to sink into passing Prop. 16, which would make it difficult for municipal governments to break into the electricity business by requiring a two-thirds vote at the ballot before any such efforts could get underway.

Last month, PG&E executives notified shareholders that the estimated $35 million expenditure for the Prop. 16 campaign would affect individual share values by 6 cents to 9 cents. Following on the heels of this news brief was the revelation that PG&E CEO Peter Darbee received a total compensation of $9.4 million in 2009, reflecting a 9 percent pay spike from the previous year, according to the Associated Press.

Since PG&E Corp., the parent corporation, derives 100 percent of its revenue from PG&E Co., the utility company regulated by the California Public Utilities Commission, critics have argued that PG&E is using ratepayers’ money to finance a campaign ultimately designed to limit ratepayers’ ability to choose their electricity provider.

As the utility seeks to alter the state constitution with Prop. 16, it is also boldly pursuing a rate hike of roughly 20 percent by 2011. Winning the Prop. 16 campaign could trigger an economic boon for PG&E since it would dramatically decrease the potential for municipal competitors to spring up and win over customers with lower rates, cleaner power, and more reliable service. Locking in such a monopoly would leave consumers with little choice but to endure rate hikes.

If Prop. 16 fails, however, the utility company’s financial outlook will be dicey. If twin efforts at green, community choice aggregation (CCA) programs moving steadily forward in San Francisco and Marin County prove successful, PG&E could see a depletion of its customer base from those territories and any other municipalities that follow suit.

What this means is that the stakes are high — and PG&E is prepared to pull out every trick in the book to win the Yes on 16 campaign. And yes, there actually is a playbook for how to use deceptive tactics to win these campaigns, a copy of which was obtained by the Guardian.

PG&E’S PROPAGANDA MANUAL

The San Francisco public relations firm Solem & Associates, which has worked with PG&E for nearly 30 years, has produced a step-by-step guide tailored specifically to its anti-public-power campaign needs. This hefty insiders’ playbook is titled “Defending Your Shareholder-Owned Electric Company Against New Municipalization Threats: A Tactical Guide.”

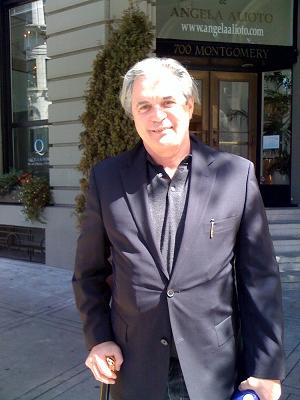

Jonathan Kaufman and Anne Solem, both executive vice presidents, are listed as coauthors. Kaufman is a white-haired guy with owl-like spectacles who can be seen regularly in the public seating section in meetings at City Hall, furiously scribbling notes, whenever the city’s green CCA program is up for discussion. He did not return the Guardian’s calls for comment.

The key strategy explained in Solem & Associates’ playbook is to create the impression that there are influential community leaders and a grassroots coalition agitating independently for the company’s agenda — when in fact the entire campaign is funded, organized, and run by one corporation.

Although the playbook never comes out to state just how the utility should go about persuading these “community allies” to see things their way, it makes it clear such allies are crucial to convince legislators, voters, and the general public that electricity programs run by municipal entities are “fraught with financial risks and other hazards.”

The playbook even recommends seeing to it that “independent” studies are published with findings that support this claim. “To provide third-party credibility to your company’s point of view … develop various reports and studies that analyze the risks and costs involved in a new public power takeover,” the playbook suggests. “It is preferable that the studies come from an independent group rather than your company.”

At certain junctures, Kaufman and Solem blatantly encourage the electric company to engage in misleading practices to hide the influence of campaign consultants working to advance a corporate agenda. “Develop opinion editorials and draft letters to the editor,” the playbook instructs. “Then ask your community supporters to personalize them and submit them to local newspapers.”

It’s interesting, given this advice, that a Twitter feed posted recently by Californians to Protect Our Right to Vote, a PG&E-bankrolled front group set up to promote the Yes on 16 campaign, highlights two different op-eds in the Fresno Bee and Sacramento Bee published within two days of one another. Both editorials were written in support of Prop.16 — one from a former sheriff of Sacramento, and the other from a former city council member of Fresno. Both editorials mention budget cuts to police and fire departments in the second paragraph. Both express surprise at the publications’ editorials against Prop. 16 in the fourth paragraph. Both cite the same statistic in the second-to-last paragraph. And both conclude with the words: “Taxpayers Right to Vote Act.” Is it a strange coincidence?

The playbook contains specific instructions for media-relations techniques, too. “Identify several community and business leaders who are willing to serve as spokespersons for your company,” the playbook recommends. “Try to keep the community leadership out in front of the reporters. Your community supporters can be much more effective with the media than perhaps your company’s own spokesperson.”

In other words: Try not to let anyone know that this is nothing more than a special-interest campaign.

Solem & Associates also suggests planting people at key local government meetings (in case of public comment, “provide them with talking points,” Solem & Associates recommends).

ON THE GROUND

How these tactics get played out in real life can be seen this year in the fight between the PG&E and Mercury front groups, and the eclectic coalition of grassroots organizations and public officials who are opposing them.

Jeff Shields, general director of South San Joaquin Irrigation District, a body governed by five elected board members, described how PG&E operates in testimony to a legislative hearing in Sacramento last month.

“PG&E attends every board meeting of SSJID, often taking video and tape recordings of our meetings, and they fund political consulting firms to campaign against our efforts and pepper us with Public Records Act requests,” he said. “Never once has a voter in our service area had the opportunity to cast a vote to allow PG&E to provide service and never have our citizens been afforded an option to vote for a PG&E Board member or attend — let alone record — a PG&E meeting.”

Yet all of the rhetoric by PG&E’s Californians to Protect the Right to Vote perversely casts the measure as about voting rights, even though this undemocratic measure protects an unelected power provider and is promoted with money that ratepayers didn’t approve for the purpose. “I am a California veteran,” Shields said. “I defended this country in uniform and I am appalled that PG&E has stated in no uncertain terms that its shareholders are paying to amend our constitution. If that is true, then it is important to examine who those shareholders are.”

He pointed out that Barclays Global Investors U.K. Holdings, Ltd., a U.K. bank, owns roughly 4 percent of PG&E shares, while JP Morgan Chase & Co. owns around 2.5 percent. “If these foreign banks and Wall Street institutional investors are truly at will to manipulate the California Constitution and this legislature has no ability to prevent that, God help us all, for the greed that motivates PG&E’s Proposition 16 is only the first thread to be pulled from the fabric that binds our society.”

John Geesman, a former member and director of the California Energy Commission, raised the possibility that if the utility is able to amass so much funding for a ballot initiative, its rates are too high. “The indisputable truth is that PG&E’s rates are set by the CPUC to provide capital to invest in needed infrastructure. If rates are so generous that PG&E can create a $35 million slush fund for political adventurism, something is seriously wrong.”

Indeed, Sup. Ross Mirkarimi, who shepherded the creation of this city’s CCA, Clean Power SF, told a recent Harvey Milk Democratic Club forum that the campaign raises larger concerns about corporate power.

“Know what? If we’re gonna lose, we go down as warriors. And if we win, then we win not for San Francisco or Marin, but we win to address the very fact that Washington is not moving in the direction we would like addressing climate change,” Mirkarimi said. “The complete corporate hubris and arrogance in that they think they can continue to operate in the way that they have is unimaginable.”

The people representing these corporations and their front groups, such as Cal-FAIR director Kathy Fairbanks, stressed to us the “broad coalitions” that support their measures. Those coalitions include “consumer groups” such as Consumers First and Consumer Coalition of California — each which seem to be comprised of only single individuals that back business-friendly measures each election.

Fairbanks defends claims that Prop. 16 would lower rates for most Californians, citing state figures that 80 percent of drivers in the state have continuous coverage and therefore could quality for the discount even if they change carriers to a provider like Mercury that generally offers lower rates than many of its competitors.

And while she grudgingly acknowledges that premium discounts for some are always offset by increases for others, she said the measures would create more “competitive markets” that would cause insurance companies to lower costs and decrease rates across-the board. “They’re going to do whatever they need to do to get more customers,” she said.

Asked whether Mercury’s bad reputation, and the difficulty many voters will have in believing that they’re spending millions of dollars to lower the premiums they collect, hurt the campaigns chances of winning, she said, “Voters are not going to do anything more than read the measures and vote in their interests.”

Rosenfield agreed that this campaign could turn on who can convince voters where their interests lie. “Here’s the issue in a nutshell: will California voters be duped by a $20 million insurance initiative campaign in which the insurance company has to hide behind a phony front group?”

COMPLICIT DEMOCRATS?

After Prop. 17 qualified for the ballot last year, the struggle to defeat it moved into the office of Attorney General Jerry Brown — who is running for the Democratic Party nomination for governor — and again Rosenfield was frustrated by the unwillingness of powerful Democrats to challenge Mercury Insurance.

The Attorney General’s Office writes the ballot title and summary for all initiatives. Given the complexity of insurance law and attractiveness of claims by proponents that the measure would save consumers money (“as much as $250 per year” for “your family,” proponents claim in their ballot arguments), the language of the summary could decide the outcome of the election.

Initially, last August, the AG’s office summarized the measure as “allows insurance companies to increase or decrease the cost of auto insurance based on a driver’s coverage history,” something that seemed to accurately capture what it would do.

“Mercury went crazy because I guess their polling showed that if voters read that it allowed insurance companies to raise your premium, they wouldn’t vote for it. So Mercury made a completely cosmetic change to the ballot measure, refiled it, and this time, magically, the title and summary comes back from Jerry Brown’s office: ‘allows insurance companies to discount your premiums.’ Nothing about raising them, nothing about surcharges. It was outrageous,” Rosenfield told us when we met with him on Feb. 9.

Consumer Watchdog formally challenged the language and issued press releases shaming Brown, which resulted in a minor scandal in which a Brown aide got fired for illegally recording a telephone conversation he had with Chronicle reporter Carla Marinucci about the issue. By Feb. 5, Brown’s office had retreated slightly, including the line “may allow insurance companies to increase costs of insurance to drivers who do not quality for a discount,” but it came below the emphasis on the discount and had weak language that didn’t reflect reality.

Eventually, after Rosenfield submitted studies proving this reality to the AG’s office, it issued language that Consumer Watchdog finds fair and accurate: “Permits companies to reduce or increase cost of insurance depending on whether driver has a history of continuous insurance coverage.”

Then something strange happened. Due to what AG’s spokesperson Christine Gaspara labeled a “clerical error,” the office inadvertently sent the old, weaker “may allow” language over to the Secretary of State’s Office. And because they didn’t realize this before the deadline passed, the AG had to sue the state and its ballot printer to get the correct language in the voter guide.

On March 12, Judge Allen Sumner ruled against Mercury, so the language will read: “Will allow insurance companies to increase costs of insurance to drivers who do not have a history of continuous coverage,” which the official ballot argument against Prop. 17 says will be “$1,000/year (based on Mercury’s numbers).”

Meanwhile, Rosenfield has also been jousting with Assembly Member Dave Jones (D-Sacramento), who is running for Insurance Commissioner this year, trying to shore up his opposition to Prop. 17 over the last few months. When we spoke last month, Rosenfield said Jones privately said he opposed the measure but had yet to do so publicly.

But Jones, who has a strong voting record supporting consumer rights, told us the criticism wasn’t accurate, and that he has consistently opposed the measure. “As I campaign throughout the state, I point to Prop. 17 as a measure that we should defeat … Certainly what Mercury is proposing in Prop. 17 would be bad policy and I oppose it. It undermines Prop. 103.”

Like Rosenfield and other critics of the measure, Jones said the measure is bad for all Californians because it makes insurance more expensive for those who haven’t had coverage. “The danger here is that the dramatic price increases could cause these drivers to drive without insurance — and that is dangerous for all of us,” reads a statement on his Web site.

But the cached Web site function on Google shows that statement was the only one of nine issue statements that wasn’t on the site as of Jan. 30. Asked when the statement was posted, Jones told us he directed staff to include it “some time ago, but we’ve had some issues with our site. It may have gone up recently for all I know.”

Jones’ Democratic primary challenger, Assembly member Hector de la Torre (D-Los Angeles County), has made an issue of his stand on the measure, telling us, “I came out very clearly and strongly on the measure and I wasn’t calculating or cautious … I came out against it months ago and I’m working within the Democratic Party to have them oppose it.”

The state party has yet to take a stand on the measure, and neither Democratic Party executive director Bob Mulholland nor chair John Burton returned our calls on the issue, just as Rosenfield told us he “can’t get Burton to return my calls.” But he remains hopeful the party will oppose the measure at its April convention and put money into defeating it.

“I’d like to think the Democrats will stand up against this insurance company, but Mercury Insurance is very politically connected and the Democratic Party, as we know all too well lately, doesn’t seem to have that kind of backbone,” Rosenfield said.

San Francisco Democratic Party chair Aaron Peskin said he’s confident the state party will join the fight to defeat it: “This is a complete abuse of the initiative process and the voters of California should not be fooled.”

BAD ACTORS

Rosenfield isn’t the only one who has battled with Mercury for many years. “I’ve been after them for 20 years, so this is not a new issue for me,” said U.S. Rep. John Garamendi (D-East Bay), who served as California’s first Insurance Commissioner from 1991 to 1995 and then again from 2003 to 2007. “He [Joseph] has refused to accept the fact that the world has changed around him.”

Beyond just trying to change the rules, Mercury has blatantly ignored them, as a decade’s worth of documents from the Department of Insurance that were released last month show, triggering upcoming legislative inquiries. In 275 pages unearthed by the Chronicle and then obtained by the Guardian, Mercury documents show the company illegally discriminating against certain professions, including soldiers, artists, bartenders, and traveling salespeople.

The Department of Insurance, now headed by a Republican, singles out Mercury as an especially bad actor with a history of hostility to regulation. As Rosenfield told us Feb. 9, “Here’s what California Insurance Commissioner Steve Poizner said about Mercury in a case that’s actually going to be heard tomorrow in Oakland. This is a quote: ‘Mercury’s lengthy history of serious misconduct and its attitude, contempt towards and/or abuse of its customers, the commissioner, its competition, and the Superior Court are all relevant to determining the penalty needed to best ensure the protection of the public for future violations and wrongdoing.’ In my 22 years of working on insurance stuff, I’ve never heard the Department of Insurance refer to a company like that.”

And here in San Francisco, the Guardian has a long history of exposing political corruption by PG&E, from essentially bribing local officials to give it control of the city electricity system — in direct violation of the Raker Act, the federal legislation that authorized the city to construct O’Shaughnessy Dam — to illegally funneling money into anti-public-power campaigns (one such violation in 2002 resulted in the largest fine ever issued by the San Francisco Ethics Commission).

The record on both companies is clearly malevolent, their political dealings utterly corrupt. Good government advocates say Props. 16 and 17 represent a clear litmus test on the power of corporations to push their interests ahead of the general public’s in California.

“To me, it’s a classic case study of what’s going on with the initiative process in California and politics in general,” said Derek Cressman, western regional director of Common Cause. “These are two initiatives literally sponsored by corporations to push very narrow interests.”

“They are laws designed to give a financial advantage to a specific industry or company,” Garamendi said, adding that he is afraid the effort may be successful. “Money talks. It always has, particularly in propositions, and the odds are money will talk again.”

Sen. Mark Leno (D-SF), who also opposes both measures, was a bit more hopeful: “Californians have been savvy in the past, and I do believe they’ll be able to see through the tens of millions of dollars in misleading ads.”