steve@sfbg.com

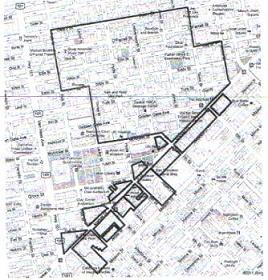

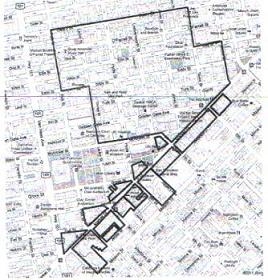

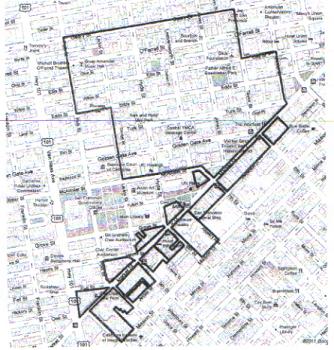

A Guardian review of the voluminous e-mails and other public records behind the proposed Mid-Market tax exclusion zone shows how public officials and private power brokers promised millions of dollars in benefits to Twitter and greatly expanded the tax-exclusion zone to unrelated properties with little explanation, concern over impacts, or understanding of how it would affect city finances.

The result was a proposal that could cost the cash-strapped city more than $17 million — a cost that even the city’s fairly conservative economist Ted Egan told the Guardian isn’t justified for many of the properties that were included in the proposal, particularly the large commercial office buildings along Market Street and the small businesses in the Tenderloin.

“It’s giving taxes away to properties that are going to fill up anyway,” said Egan, who recommended several changes to lessen the proposal’s cost, even though he supports giving a tax break to Twitter and thinks the deal will be a net positive if it stimulates business development as much as its backers hope.

The proposal would exempt companies in Mid-Market and the Tenderloin from paying the city’s 1.5 percent business payroll tax on any new jobs they create for six years. It was sweetened even more for Twitter — city officials promised the company a new Muni line, police foot patrols, and various other tax credits and exemptions to improve Twitter’s cash flow, the documents show.

The Mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development worked almost full-time on the deal for several months to keep Twitter from following through on its threat to leave town. Indeed, OEWD staffers don’t even acknowledge that the tax break is a loss to city coffers, arguing the city would lose money if Twitter leaves and keeping the company here will increase property taxes and rents in the Mid-Market area.

Yet there is little in the documents to indicate how real that threat is or whether the legislation will convince the company to stay here, and Twitter hasn’t responded to inquires from the Guardian or other media outlets.

Egan pointed to a reason for Twitter to leave that hasn’t been part of the public discussion to date. The city’s payroll tax applies to stock options — and Twitter would be on the hook for as much as $40 million in taxes if the company goes public. But he said that could be addressed more directly without the broader giveaway.

OEWD head Jennifer Matz said she trusts Twitter executives and “they are out the door if we don’t do this.” She also said she disagrees with Egan that the city is giving away more than it needs to and “there is no question in my mind it will bare its fruits.”

Yet she also acknowledged the difficult precedent this deal is setting and said she’s already fielded regular calls from other companies asking for their tax break. “I’ve had multiple conversations like that,” she said. “We tell the other businesses, ‘we’re sorry.'”

Not everyone shares her faith in the power of tax breaks, with progressives and the city’s biggest public employee union opposing the deal. Critics have said Twitter is a rich company that is essentially trying to shake down city taxpayers, despite previous assurances to remain here. After then-Mayor Gavin Newsom made one of many visits to the company on March 10, 2009, Twitter officials wrote on the company blog, “We assured Mayor Newsom that as Twitter grows, we’ll continue to keep our headquarters here in San Francisco.”

That all changed the next year as Twitter officials looked to expand and relocate into the SF Mart building at Market and Ninth streets.

“OEWD staff has been actively engaged with Twitter since February of 2009,” Matz wrote in a Jan. 18 memo to Sup. Jane Kim soliciting her support for the tax breaks.

But it wasn’t until October 2010 that records show the deal really taking shape. According to memos from Matz, Twitter CFO Ali Rowghani met with Newsom and told him that the company’s top choice for a new headquarters location was SF Mart (which also happened to be where Newsom’s campaign for lieutenant governor was headquartered at a discounted rent) but Twitter’s concerns were “public safety, transportation, neighborhood conditions, [and] cost.”

The memos show Newsom returned to Twitter on Oct. 29 with his chief of staff, Steve Kawa, Police Chief Jeff Godown (then assistant chief), and Matz — promising not just the payroll tax break and enterprise zone tax credits but 18 hours a day of police foot patrols in the area and the creation of a new Muni express line, 47A, between the Caltrain Station and the Twitter headquarters.

None of those costs are being figured into the deal. Matz said the new Muni line was a service restoration that has already been approved but not yet funded, and that the foot patrols would simply be absorbed into the police budget. These are just a few of the many guesstimates and unaccounted for costs in this highly complex deal.

EXPANDING THE GIVEAWAY

Throughout the month of January, new properties kept getting added to the district by various people, from OEWD staffers to Sup. Jane Kim — who greatly expanded the district and refuses to answer Guardian questions about why — and Randy Shaw, who runs the Tenderloin Housing Clinic and the Beyond Chron blog and has been a vocal tax-break supporter.

“Payroll tax thing is going to happen and Randy Shaw wants us to add the Uptown Tenderloin Historic District!” OEWD’s Amy Cohen wrote on Feb. 2 to a real estate consultant with the Northern California Community Loan Fund.

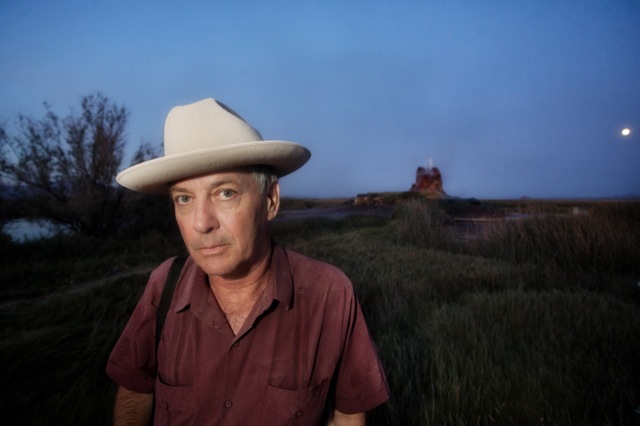

None of the requests for expanding the tax exclusion zone included an explanation of why that property should be in — and in each case they were added to the area without question. The only possible exception was when the Warfield Building was added Jan. 7 after OEWD learned Burning Man was seeking to rent headquarters space there. Yet Burning Man founder Larry Harvey told us it planned to move to mid-Market with or without the tax break, and that it is now negotiating for a different building, although the Warfield remains in the tax exclusion district.

“Can you add 875 Stevenson to the boundaries and send the revised map? Thx,” one OEWD staffer wrote to another on Jan. 13.

“I want to add one more area: I want to go halfway down the block between Fifth and Sixth grabbing everything heading east up to the Cityplace properties,” Matz wrote to another OEWD staffer on Jan. 14.

New properties were being added right up to the point that the legislation was introduced on Feb. 9. The day before, Shaw wrote to Matz and OEWD’s Amy Cohen telling them that the owner of the Hastings Law School garage “should get the exemption if he thinks it might help,” and that property was added. Cohen then gave Shaw credit in an e-mail to UC Hastings CFO David Seward: “We’re going to put your properties in. Randy is good with it!”

Even some OEWD staffers seemed surprised that the tax exemption area had grown so far beyond its original borders. “Wow, when did the entire TL get thrown in?” OEWD Project Manager Lisa Pagan wrote to Cohen in a Feb. 8 e-mail.

But Matz defended the expansion and said it wasn’t as willy-nilly as it appears. “There was a lot more conversation than was reflected in those e-mails,” she told us. “The boundaries evolved due to more thorough thinking.”

Yet she acknowledged it’s tough for skeptics of the deal to determine why properties were included, whether political favoritism played a role, or who stands to benefit from the decisions.

As OEWD staff prepared memos for the mayor and supervisors on Jan. 13, they also discussed talking points for the media and how to share credit for those outside City Hall. As Cohen wrote to another OEWD staffer, “Randy Shaw — we are crediting him with coming up with the idea. He told me he talked to a bunch of people, including supervisors, and got lukewarm reception.”

That assessment runs contrary to how proponents have publicly claimed the idea has enthusiastic support in City Hall. Indeed, it wasn’t until Egan’s report came out one day before the first public hearing that proponents of the deal started discussing why they had expanded the boundaries so far.

QUESTION OF ALLEGIANCE

For those who aren’t simply fiscal conservatives who automatically support corporate tax breaks, the wisdom of this deal relies on whether people believe Twitter is headed to Brisbane if its demands aren’t met.

“The real question is do you believe Twitter is leaving if they don’t get this,” Egan said. “It’s impossible to say.”

He’s convinced that the high stock option price tag would be enough to cause most companies to leave town. But OEWD seems to just take corporate claims at face value, as it did when Oracle CEO Larry Ellison said he needed $128 million in public subsidies to hold the America’s Cup boat race here (see “The biggest fish,” Nov. 30, 2010) only to later agree to a greatly reduced public subsidy.

Even the two supervisors who are sponsoring the legislation, Kim and Board President David Chiu, don’t seem to have had the opportunity to assess the deal free of OEWD’s advocacy for a company that has refused to share any financial records with the city.

Matz set up phone conversations between Twitter’s Rowghani and Chiu and Kim on Jan. 21, sending the two supervisors an e-mail that day recommending they ask three questions of Twitter: why the company needs the tax break, whether it would commit to keeping its entire headquarters here, and what community partnerships it would commit to.

She then sent Rowghani an e-mail that same day letting him know what the supervisors would be asking and what they wanted to hear. Matz told him both supervisors support the deal “but need to hear from you how and why payroll taxes moves the needle for you.”

Matz told us she sees nothing wrong with coaching Twitter.

“It was more like facilitating a first date between friends,” Matz said of sharing information with Twitter. “I was simply trying to facilitate a productive conversation.”

Drafts of a community benefits package were watered down to please Twitter, the documents show. Language claiming that Twitter will try to hire more San Franciscans who don’t have four-year college degrees became a pledge to work with city officials on “a mutually agreeable program to train” those individuals.

In the end, even Matz admits that the community benefits agreement is too weak and vague: “We want to work with them in making that stronger,” she said.

Shaw, the records show, functioned almost as a de facto member of the OEWD staff, strategizing with officials while writing articles in Beyond Chron.org that tried to retain a thin veneer of journalistic objectivity, such as “Landmark Measure Would Revitalize SF’s Mid-Market and Upper Tenderloin Area,” which he wrote and forwarded to Matz on Feb. 8.

“Article is perfect. This is game-changing, largely for the signal it sends about the city’s commitment to improving the area,” she wrote in response.

FACTS AND FICTIONS

In addressing progressive critics of the deal, Kim said she greatly improved the proposal before agreeing to sponsor the legislation, insisting that its duration be reduced from eight years to six, its boundaries be expanded, and the payroll tax exclusion be limited to new jobs that a company creates rather than all its employees.

Yet the documents show that OEWD had been developing two options for the legislation, total jobs and “net new jobs,” since well before Kim got involved.

The OEWD also sold the deal to supervisors and the public during the month of January with figures it couldn’t support — such as repeatedly claiming that the creation of 300 jobs at Twitter would create 400 additional jobs and $174 million in economic activity. Yet when the OEWD finally checked those figures with Egan on Feb. 2, he wrote that “it is only 100 additional jobs” and “not sure where you get $290,000” as the economic value per job.

Yet for the OEWD and the other proponents of this deal, the record shows a determination to get the deal done — and then make it sound good. “Make the narrative as strong as possible,” Cohen wrote to Matz on Feb. 1, passing on the concerns expressed by Kim’s office. “Ultimately, we need to be able to show that this is not a net loss, it is a net gain.”

But behind the scenes, the actual cost to taxpayers of retaining Twitter is being obscured by a variety of financial mechanisms and budget decisions by city departments.

Even Kim’s shortening of the program brought new demands by Twitter. In a Feb. 9 e-mail from Matz to Chiu and Kim, she wrote, “Twitter told me that they agreed that the six-year time frame works only if 1) their short term cash flow issues are addressed and 2) the exemption for stock options is extended to eight years.” So Matz said she would “noodle on other financial mechanisms, including Mills Act Historic Tax Credit and New Market Tax Credits.”

The public won’t get a chance to weigh in on these details. On Feb. 4, when an OEWD staffer wrote to Matz that the City Attorney’s Office recommended the legislation call for another public hearing after OEWD develops rules and regulations for implementing the policy, Matz replied simply, “No!”