Pianofight takes on Tchaikovsky — and the death of theatre — and Boxcar’s Hedwig has us humming in the shower.

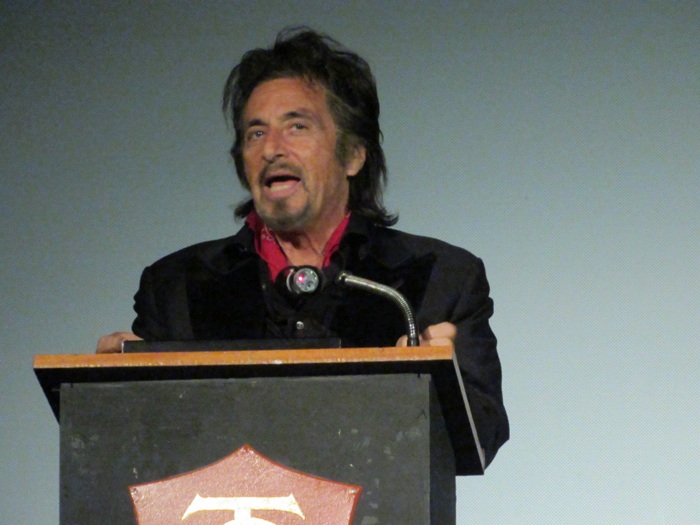

Zombies are so over. The next monster movie massacre sensations are totally going to be murderous waterfowl, so props to PianoFight and Mission CTRL for jumping on that bandwagon before it even rolled out of the studios with their ensemble-created, ballet-horror-comedy, Duck Lake. When Raymond Hobbs as theatre director Barry Canteloupe (sic) boasts “no one has ever done what we are about to do,” while tweaking his own nipples, you get the feeling he’s talking about more than the production he is supposedly directing — a musical theatre adaptation of Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake.”

“Duck Lake” opens innocuously enough with a series of scenes focused on Canteloupe’s directing methods, which includes literally suckling his wary charges on the “teat of creativity.” These last perhaps a smidge too long, and fail to foreshadow the eventual horrors that await the hapless cast, but they do drive home the sheer awfulness of being cast in a Canteloupe production. Shades of Waiting for Guffman’s Corky St. Clair color Hobbs’ turn as the narcissistic Canteloupe, whose singular theatrical vision has seen him voted the “best up-and-coming director” 10 years in a row, mainly for previous remixes of the iconic ballet, including a scat porn. Isolated on the banks of Duck Lake for a weekend rehearsal intensive, Canteloupe’s misfit cast members work hard to keep their simmering doubts from derailing the “process,” even when their prima donna “Prince” (Sean Conroy) mysteriously disappears, leaving only a bloody scrap of his cranium behind.

Cue encroaching pandemonium. Murdered park rangers! A groundskeeper with a terrible secret! Obnoxious jet-skiers! An awkward love story tangent! Tortured showtunes! Bloodthirsty, vengeful ducks! And the indescribable horror known only as the Harem Master (Rob Ready); a drama camp kid gone oh so very wrong. In the best tradition of Hollywood villains everywhere, the Harem Master gets to deliver a stirring speech regarding his motivations, which diverges into a reflection on the long slow decline of attendance in theatres, attributed by the loincloth-clad duck enthusiast in part to directors’ insistence on mining the classics for inspiration rather than creating new work. So meta! Truthfully “Duck Lake” itself is probably not in danger of being remounted 400 years from now, but it may yet prove itself useful to future generations, at a minimum for its handy tips on how to drive away angry flocks of mutant ducks. The day may be coming that such information will prove indispensable.

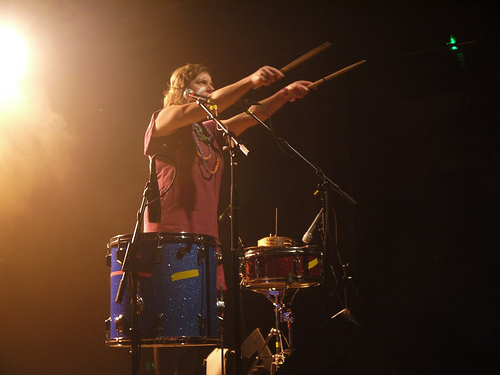

Speaking of classics, though, Boxcar Theatre’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch, sizzled for a scant, two-weekend run, like an incandescent streak of showbiz lightning. Hitting upon a novel way to fully embellish each distinct facet of Hedwig’s somewhat fractured personality, director Nick Olivero cast twelve separate actors as the would-be rock star, adding a free-for-all twist to the already anarchic, transgendered glam-rock musical. From the fierce, punk snarl of Brionne Davis, to the coyly nude antics of Ste Fishell, to the Aretha Franklin-esque majesty of Michelle Ianiro, a dozen Hedwigs reenacted the tragic events of their backstory to the patrons of “Bilgewater’s,” with grace, guts, and a staggering array of platinum wigs. If you missed its too-short summer run, all hope is not lost. Rumor has it that a late autumn remount is not out of the question. Hopefully by then I’ll have stopped incessantly humming “Wig in a Box” in the shower, though honestly I’d rather be humming Stephen Trask than Tchaikovsky any day, so there’s that.

DUCK LAKE

$25, through July 28

The Jewish Theatre

470 Florida, SF

www.pianofight.com

www.missionctrlcomedy.com