Jennie Ottinger’s last solo painting show at Johansson Projects, “ibid,” presented an assortment of ghostly figures — ballerinas, nurses, schoolchildren, businessmen — lifted from found photographs. The less-is-more aesthetic of Ottinger’s small oil and gouache canvases underscored the fact that, save for the recovered images used as source material, the everyday people depicted in them had long been lost to history.

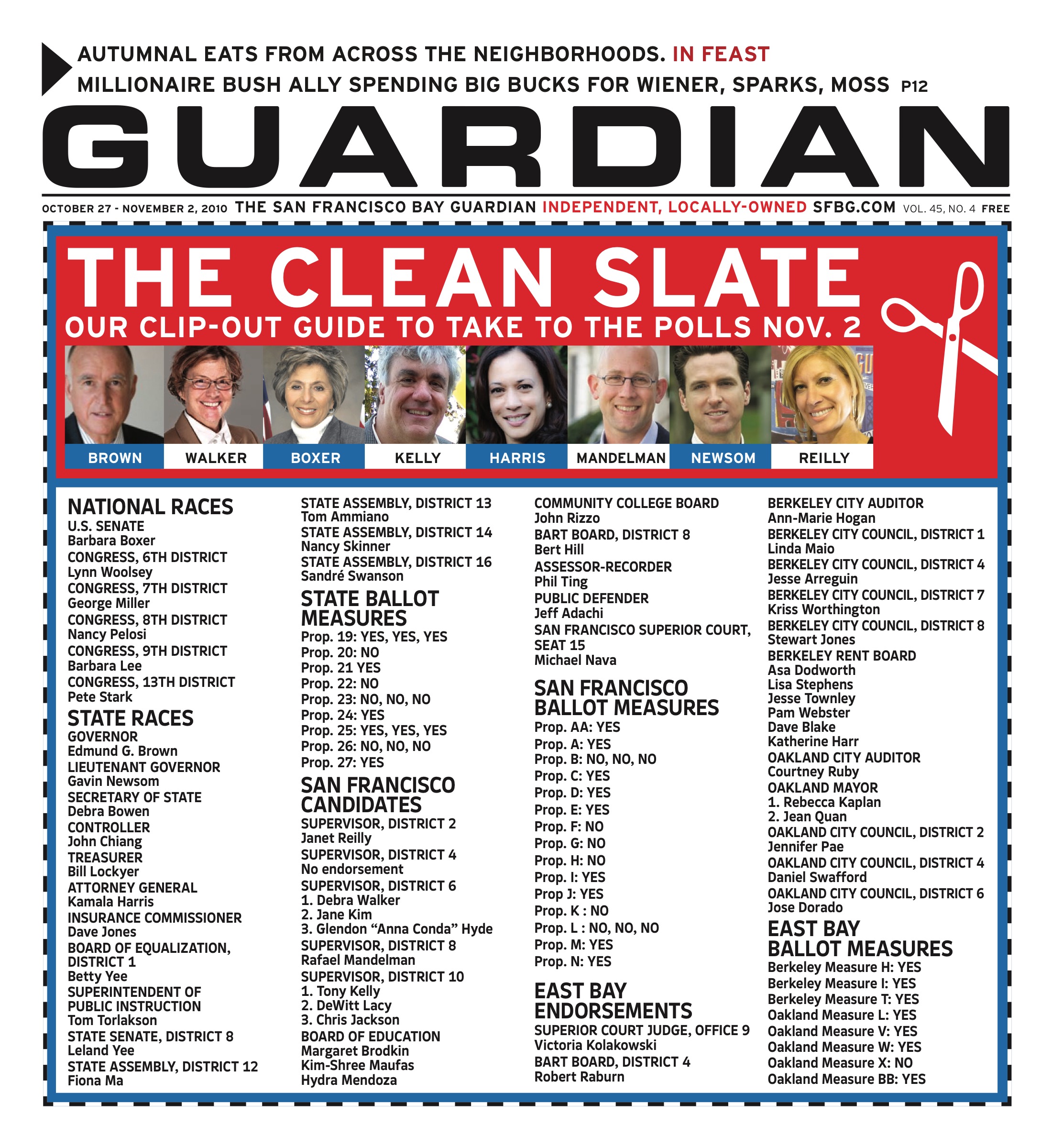

The same could hardly be said of the authors Ottinger breezily engages with in her latest show, “Due By,” in which she casts a gimlet eye on William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, David Foster Wallace, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Harper Lee, John Updike, and Leo Tolstoy, among other notable figures of the modern Western literary canon.

Ottinger has essentially remade these authors’ best-known works in her own image with her own images. In addition to painting scenes from titles such as The Loved One and To Kill A Mockingbird, she has also created new covers for them (based on the design of older editions) enfolding her art around actual books. The contents of the books don’t match their titles. Their plastic slipcases, though, are a clever nod at authenticity.

On one wall these new-old books have been stacked horizontally into humorous thematic groupings whose titles frequently double as groan-inducing punchlines: the Madame Bovary, Couples, and Anna Karenina stack is called Why Buy the Cow When You Can Get the MILF For Free? Another short stack that includes Lolita, Sons and Lovers, and Oedipus Rex is titled, appropriately enough, Inappropriate Lovers.

Also throughout the gallery are single volumes, propped open on shelves. Ottinger has glued together the books’ pages and carved out small rectangular spaces into which she has placed her own summaries of the re-covered work, which you are allowed to pick up and leaf through.

Ottinger’s retellings — handwritten in a tiny, tidy scrawl that resembles birdtracks across fresh snow — are by far the best thing in “Due By.” Her observations are pithy, and at times, flash an understated brilliance. Ottinger is also, on occasion, not above proclaiming her ignorance of the text she’s writing on and doesn’t hesitate to quote Wikipedia and SparkNotes for backup.

Here she is on Anna Karenina‘s titular doomed heroine: “We will soon see evidence of her extraordinary relationship skills.”

Or the protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: “Much like tofu, he adopts the qualities of those around him.”

And I challenge any English PhD to come up with a more perfect gloss on As I Lay Dying‘s Budren clan as, “Holy shit! This family is cursed. Very National Lampoon’s Vacation.”

If Ottinger were a high school student, she would be the bright kid who always makes wisecracks in class because she’s bored with or understimulated by her surroundings, and not necessarily by the assigned reading (I wonder, in fact, if Ottinger was that student). Her writing, for all its glibness and front-loaded superficiality, carries a palpable amount of affection for the texts. Ottinger’s sassiness is an informed sassiness; it lacks the underlying vitriol of true snark.

In other words, Ottinger’s armchair criticism is the sort that the Internet — and blogs, in particular — has made us more accustomed to. At the same time, educators attempting to teach any of the texts featured in “Due By,” have had to become more adept at sniffing out the lines in their students’ papers lifted from the same Wikipedia and SparkNotes entries that Ottinger playfully quotes. You can read Anna Karenina in its entirety online, or you can find a million ways to get around reading it and still turn in a term paper on “the death of the heart.”

Mind you, I don’t think Ottinger is clutching her pearls over the fate of the literary canon (or the book as object, or the coarsening of pedagogy, etc.) in the age of Google. If the smart, funny, and lovingly crafted objects she has created in “Due By” must be burdened with a takeaway message about the way we read now, I’d like to quote one of the great antiheros of television, Don Draper: “Change isn’t good or bad. It just is.”

MAGIC EYES

With Ed Moses’ dazzling acrylics, what you see is what you get. That’s not a diss by any means. Rather, don’t expect something else to emerge if you give into the temptation to slowly cross and uncross your eyes while staring down one of the textile-like paintings in “Wic Wac,” Moses’ current show at Brian Gross Fine Art.

Moses — a L.A. veteran who had his first show at the city’s legendary Ferus Gallery in 1958 — identifies as an abstract artist, even though paintings such as Anima Kracker can’t help but cause pattern recognition: their fractal-like smears of off-set yellows and purples are in fact made up of the morphed stripes, spots, and other tell-tale markings of zebras, giraffes, and tigers.

JENNIE OTTINGER: DUE BY

Through Jan. 8, 2011

Johansson Projects

2300 Telegraph Ave, Oakland

(510) 444-9140

www.johanssonprojects.com

ED MOSES: WIC WAC

Through Dec. 23

Brian Gross Fine Art

49 Geary, SF

(415) 788-1050

www.briangrossfineart.com