arts@sfbg.com

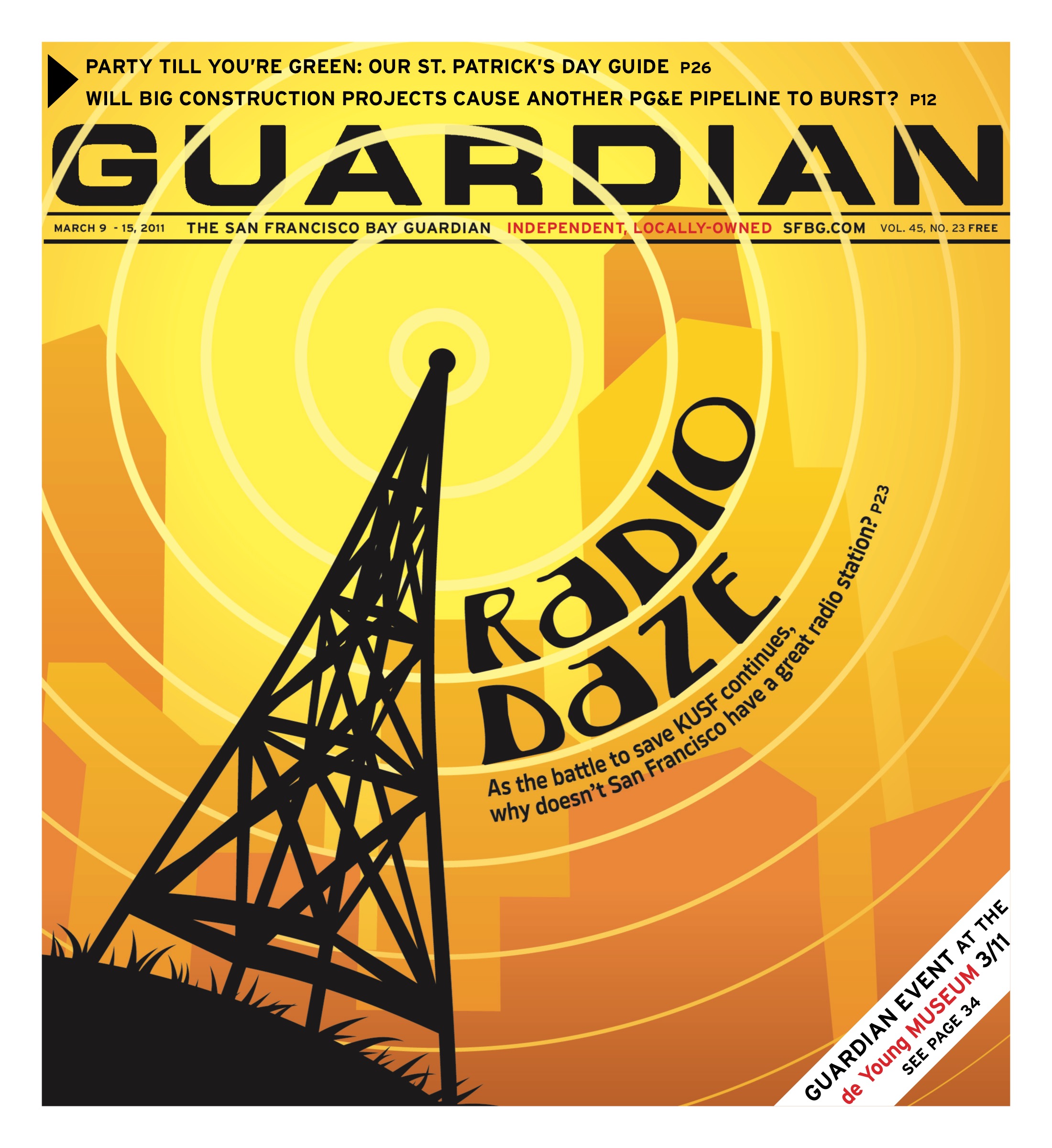

Do you remember rock ‘n’ roll radio, as the Ramones once quizzed us, ever so long ago? If not that “Video Killed the Radio Star”-era iteration, a leather-clad punky nostalgia for Murray the K and Alan Freed, then do you remember college rock when it became the name of a musical genre in the early 1990s?

I’m trying to make out its faint strains now: a sound nominally dubbed rock, but as wildly eclectic and widely roaming as the winds blowing me over the Bay Bridge on this blustery, rain-streaked afternoon. I’m not imagining it. New, shaken-and-stirred PJ Harvey nudging family-band throwback the Cowsills. Nawlins jazzbos Kid Ory and Jimmy Noone rubbing sonic elbows with winsome Tim Hart and Maddy Prior. Brit electropoppers Fenech-Soler bursting beside Chilean melody-makers Lhasa. The ancient Popul Vuh tangling with the bright-eyed art-rock I Was a King. It’s an average playlist for KALX 90.7 FM, the last-standing free-form sound in San Francisco proper — though it hails from across the bay in Berkeley.

But what about SF’s own, KUSF? A former college radio DJ and assistant music director at the University of Hawaii’s KTUH and the University of Iowa’s KRUI, I’m one of those souls who’s searching for it far too late, even though I benefited from my time in college radio, garnering a major-league musical education simply flipping through the dog-eared LPs and listening to other jocks’ shows. Like so many music fans, I got lost — searching for the signal and repelled by commercial radio’s predictable computerized playlists, cheesy commercials, and blowhard DJs — and found NPR.

Today, I’m testing the signals within — the health of music on SF terra firma radio — by driving around the city, cruising City Hall, bumping through SoMa, and dodging bikes in the Mission. KALX’s signal is strong on the noncommercial side of the dial, alongside the lover’s rock streaming from long-standing KPOO 89.5 and the Strokes-y bounce bounding from San Jose modern rock upstart KSJO 92.3, whose tagline promises, “This is the alternative.” But KSJO’s distinct lack of a DJ voice and seamless emphasis on monochromatic Killers-and-Kings-of-Chemical-Romance tracks quickly bores, slotting it below its rival, Live 105.

Dang. I wind my way up Market to Twin Peaks. Waves of white noise begin to invade a Tim Hardin track. KALX’s signal fades as the billowing, smoky-looking fog rolls majestically down upscale Forest Hill to the middle-class Sunset. But I can hear it — with occasional static — on 19th Avenue, and later, in the Presidio and Richmond.

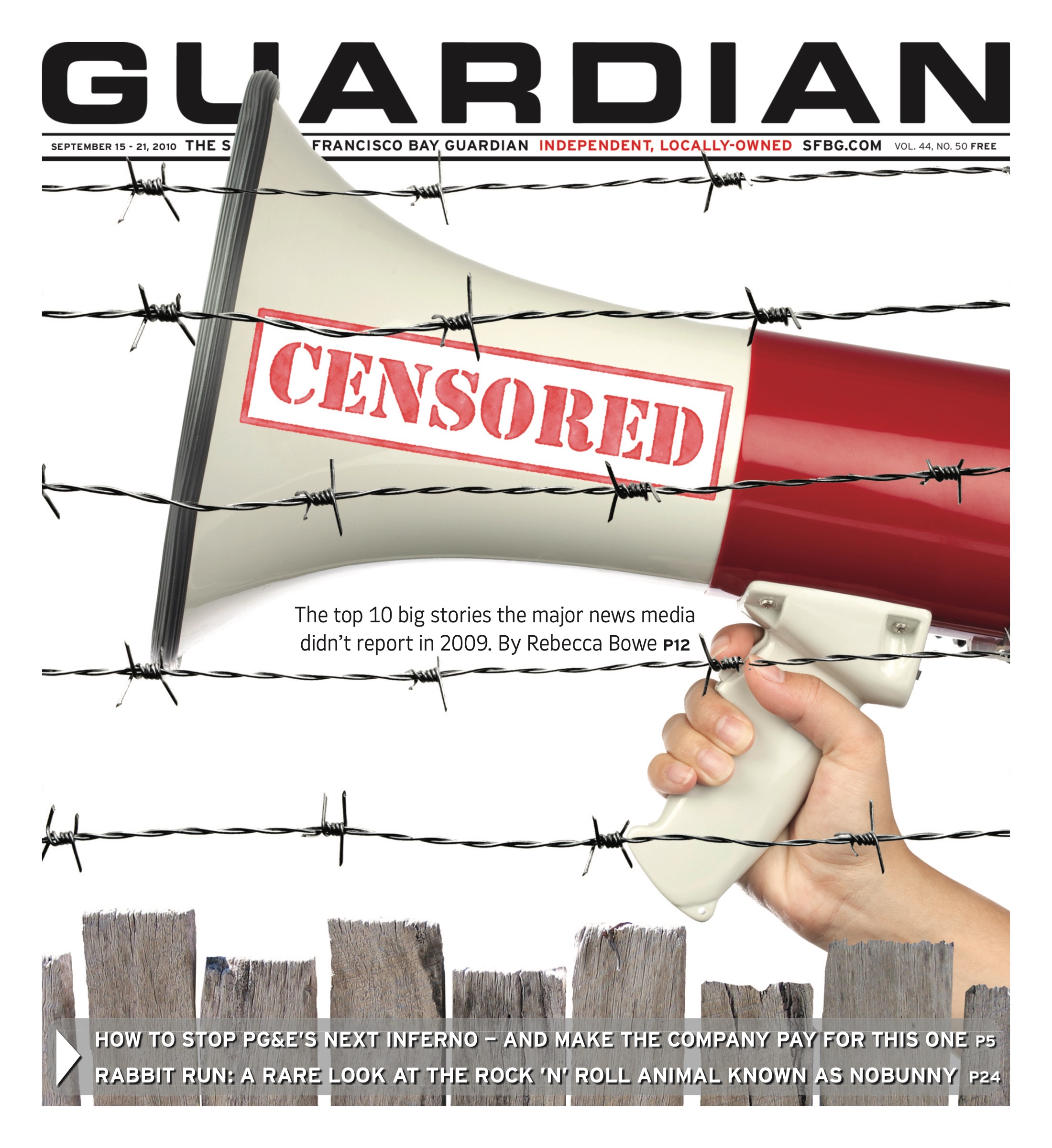

Throughout, KUSF’s old frequency, 90.3, comes through loud and clear — though now with the sound of KDFC’s light-classical and its penchant for swelling, feel-good woodwinds. The music is so innocuous that to rag on it feels as petty and mean as kicking a docile pup. But I get my share of instrumental wallpaper while fuming on corporate phone trees. It’s infuriating to realize that it supplanted KUSF, the last bastion of free-form radio in SF proper. Where is the free-form rock radio? This is the city that successfully birthed the format in the 1970s, with the freewheeling, bohemia-bred KSAN, and continued the upstart tradition with pirate stations such as SF Liberation Radio. Doesn’t San Francisco deserve its own WFMU or KCRW?

FEWER INDEPENDENTS, MORE CONSOLIDATION

Online radio — including forces like Emeryville’s Pandora and San Diego’s Slacker Radio — provides one alternative. This is true for listeners who use the TiVo-like Radio Shark tuner-recorder to rig their car (still the primo place to tune in) to listen to online stations all over the country. The just-launched cloud-based DVR Dar.fm also widens the online option.

Nevertheless, online access isn’t a substitute for free radio air waves. “We get the wrong impression that everyone is wired, and everyone’s online, and no one listens to terrestrial radio,” says radio activist and KFJC DJ Jennifer Waits. “Why then are these companies buying stations for millions of dollars?”

Waits and KALX general manager Sandra Wasson both point to the consolidation that’s overtaken commercial radio since deregulation with the Telecommunications Act of 1996 — a trend that has now crept onto the noncommercial end of the dial.

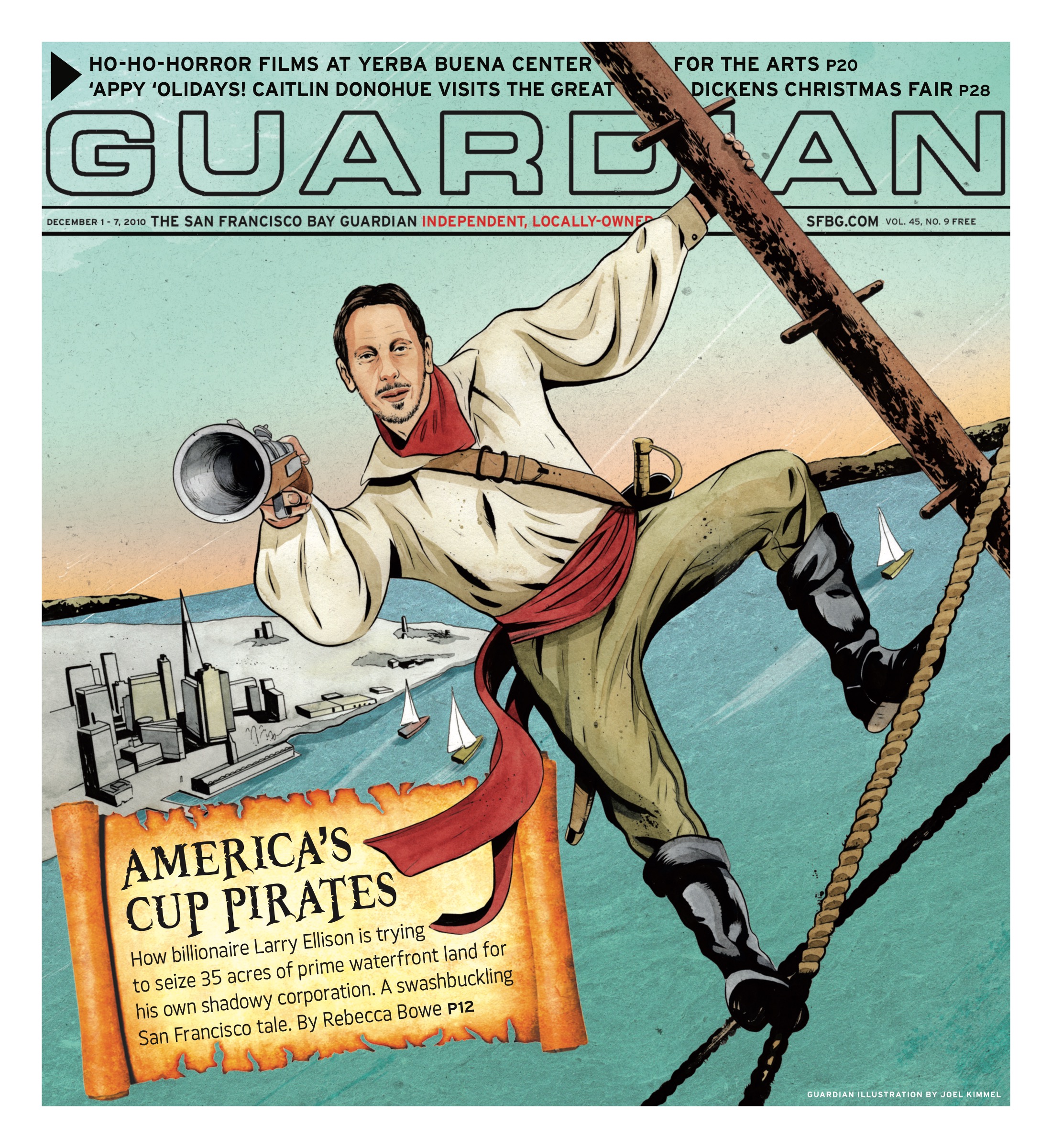

As competition for limited bandwidth accelerates (in San Francisco, this situation is compounded by a hilly topography with limited low-power station coverage) and classical radio stations like KDFC are pushed off the commercial frequencies, universities are being approached by radio brokers. One such entity, Public Radio Capital, was part of the secretive $3.75 million deal to sell KUSF’s transmitter and frequency. Similar moves are occurring throughout the U.S., according to Waits. She cites the case of KTXT, the college radio station at Texas Tech, as akin to KUSF’s situation, while noting Rice and Vanderbilt universities are also exploring station sales.

“The noncommercial band is following in the footsteps of the commercial band in the way of consolidation,” Wasson says, from her paper-crammed but spartan office at KALX, after a tour of the station’s 90,000-strong record library. Wire, Ringo Death Starr, and Mountain emanate from the on-air DJ booth, as students prep the day’s newscast and a volunteer readies a public-affairs show. “Buying and selling noncommercial radio seems to me very much like what used to happen and still does in commercial radio: one company owns a lot stations in a lot of different markets and does different kinds of programming in different markets. Deregulation changed it so that 10-watt stations weren’t protected anymore. There were impacts on commercial and noncommercial sides.”

Lack of foresight leads cash-strapped schools to leap for the quick payout. “Once a school sells a station, it’s unlikely it will be able to buy one back,” says Waits. “Licenses don’t come up for sale and there are limited frequencies. They have an amazing resource and they’re making a decision that isn’t thought-through.”

DREAMING IN STEREO

There are still people willing to put imagination — and money — behind their radio dreams. But free-form has come to sound risky after the rise of KSAN and FM radio and the subsequent streamlining and mainstreaming of the format.

Author and journalist Ben Fong-Torres, who once oversaw a KUSF show devoted to KSAN jocks, cites the LGBT-friendly, dance-music-focused KNGY 92.7 as a recent example of investors willing to try out a “restricted” format. “They were a good solid city station that sounded quite loose,” he explains. “But even there they weren’t able to sell much advertising because they were limited to the demographic in San Francisco and they couldn’t make enough to pay their debts.”

Nonetheless, Fong-Torres continues to be approached by radio lovers eager to start a great music station. “I’ve told them what I’m telling you,” he says. “It’s really difficult to acquire a stick in these parts, to grab whatever best signals there are.” This is especially true with USC/KDFC rumored to be on a quest for frequencies south of SF.

“There are some dreamers out there who think about it,” muses Fong-Torres. “A single person who’s willing to bankroll a station just out of the goodness of his or her heart and let people spread good music — someone like Paul Allen, who did KEXP in Seattle.”

THE FIGHT TO SAVE KUSF

The University of San Francisco has touted the sale of KUSF’s frequency and the station’s proposed shift to online radio as a teaching opportunity. But the real lesson may be a reminder of the value of the city’s assets — and how easily they can be taken away. “We’re learning how unbelievably sacred bandwidth is on the FM dial,” says Irwin Swirnoff, who was a musical director at the station.

Swirnoff and the Save KUSF campaign hope USF will give the community an opportunity to buy the university’s transmitter, much as Southern Vermont College’s WBTN 1370 AM was purchased by a local nonprofit.

For Swirnoff and many others, listener-generated playlists can’t substitute for the human touch. “DJs get to tell a story through music,” he explains. “They’re able to reach a range of emotions and [speak to] the factors that are in the city at that moment, its nature and politics. Through music, they can create a moving dialogue and story.”

Swirnoff also points to the DJ’s personally selective role during a time of corporate media saturation and tremendous musical production. “In the digital age, the amount of music out in the world can be totally overwhelming,” he says. “A good station can take in all those releases and give you the best garage rock, the best Persian dance music, everything. One DJ can be a curator of 100 years of music and can find a way to bring the listener to a unique place.”

Local music and voices aren’t getting heard on computer-programmed, voice-tracked commercial stations despite inroads of satellite radio into local news. In a world where marketing seems to reign supreme, is there a stronger SF radio brand than the almost 50-year-old KUSF when it comes to sponsoring shows and breaking new bands for the discriminating SF music fan? “People in the San Francisco music community who are in bands and are club owners know college radio is still a vital piece in promoting bands and clubs,” says Waits. “There are small shows that are only getting promotion over college radio.”

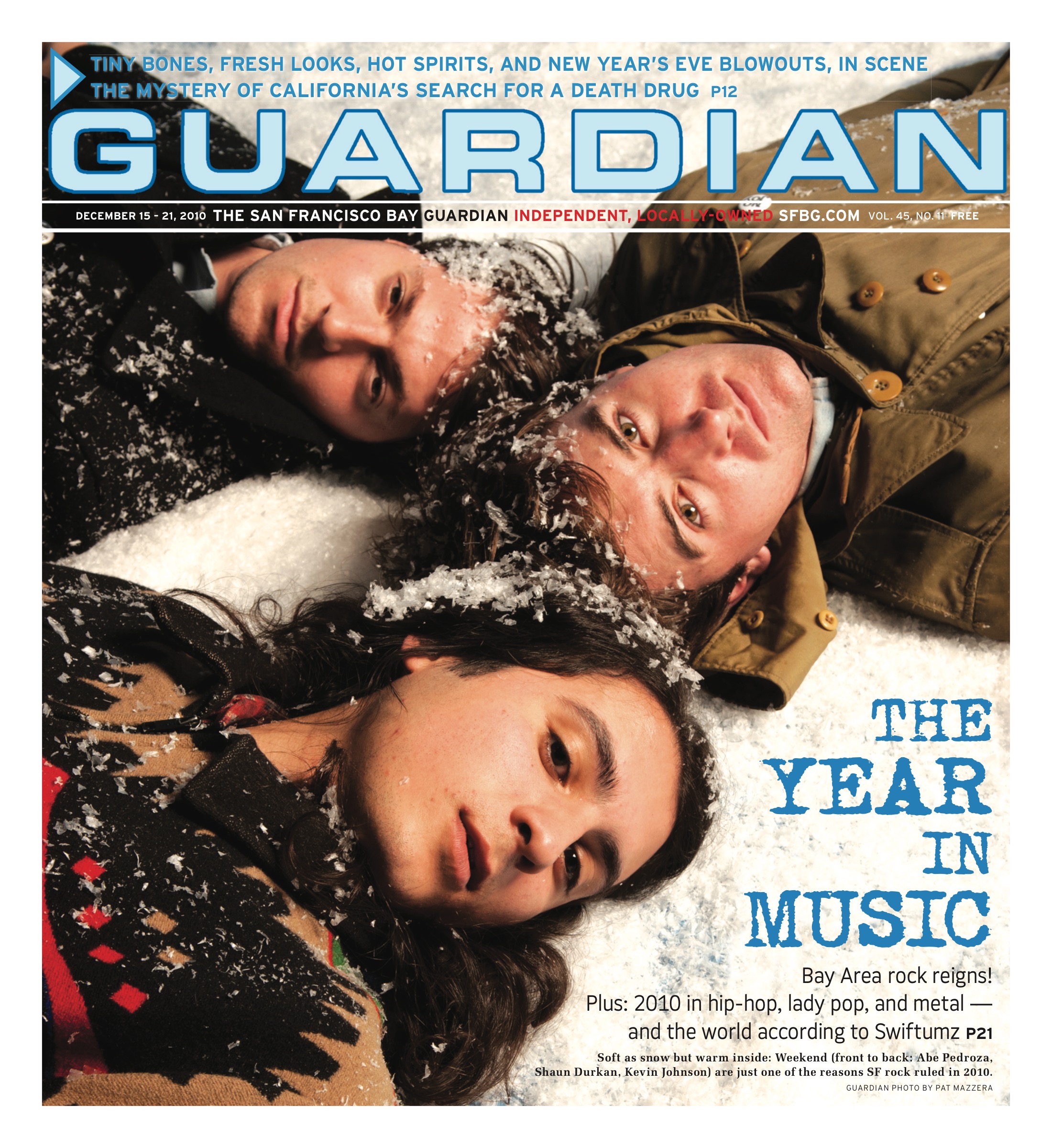

“It was a great year for San Francisco music, and we [KUSF] got to blast it the most,” Swirnoff continued. “It’s really sad that right now you can’t turn on terrestrial radio and hear Grass Widow, Sic Alps, or Thee Oh Sees, when it’s some of the best music being made in the city right now.”

PIRATE CAT-ASTROPHE — AND THE DRIVE TO KEEP RADIO ALIVE

Aside from KUSF, the only place where you could hear, for instance, minimal Scandinavian electronics and sweater funk regularly on the radio was Pirate Cat. The pirate station was the latest in a long, unruly queue, from Radio Libre to KPBJ, that — as rhapsodized about in Sue Carpenter’s 2004 memoir, 40 Watts From Nowhere: A Journey into Pirate Radio — have taken to the air with low-power FM transmitters.

After being shut down by the FCC and fined $10,000 in 2009, Pirate Cat is in limbo, further adrift thanks to a dispute about who owns the station. Daniel “Monkey” Roberts’ sale of Pirate Cat Café in the Mission left loyal volunteers wondering who should even receive their $30-a-month contributions. Roberts shut down the Pirate Cat site and stream on Feb. 20. Since then, some Pirate Cat volunteers have been attempting to launch their own online stream under the moniker PCR Collective Radio.

“We would definitely start our own station,” says Aaron Lazenby, Pirate Cat’s skweee DJ and a Radio Free Santa Cruz vet. “The question now is how to resolve the use of Pirate Cat so we don’t lose momentum and lose our community. We all love it too much to let it fizzle out like that.”

Some people are even willing to take the ride into DIY low-power terrestrial radio. I stumbled over the Bay Area’s latest on a wet, windy Oakland evening at Clarke Commons’ craftsman-y abode. The door was flung open and a colorful, quilt-covered fort/listening station greeted me in the living room. In the dining space, a “magical handcrafted closet studio station” provided ground zero for the micro-micro K-Okay Radio — essentially a computer sporting cute kitchen-style curtains and playing digitized sounds.

A brown, blue, and russet petal-shingled installation looked down on K-Okay’s guests as they took their turn at the mic. And if you were in a several-block radius of the neat-as-a-pin house-under-construction and tuned your boombox to 88.1 FM, you could have caught some indescribably strange sounds and yarns concerning home and migration. I drove away warmed by the friendly mumble of sound art.

Who would have imagined radio as an art installation? Yet it’s just another positive use for a medium that has functioned in myriad helpful ways, whether as a life link for Haitians after the 2010 earthquake or (as on a recent Radio Valencia show) a rock gossip line concerning the Bruise Cruise Fest. As Waits puts it, radio is “about allowing yourself to be taken on a musical journey rather than doing the driving yourself online.” Today it sounds like we need the drive to keep that spirit alive.