Film listings are edited by Cheryl Eddy. Reviewers are Kimberly Chun, Michelle Devereaux, Peter Galvin, Max Goldberg, Dennis Harvey, Johnny Ray Huston, Louis Peitzman, Lynn Rapoport, Ben Richardson, and Matt Sussman. The film intern is Ryan Prendiville. For rep house showtimes, see Rep Clock. For first-run showtimes, see Movie Guide.

OPENING

*Hadewijch Celine (Julie Sokolowski) is a novice nun whose superiors see her fervency — which manifests in refusing to eat or wear warm clothing in winter — as “self-love” she must rid herself of before fully committing to the religious life. They order her back into the secular world to test her faith. Back in her parents’ Parisian very upper-class home, she drifts into friendship with Yassine (Yassine Salime), a young Arab living in the projects, while refusing to return his romantic interest. Indeed, she finds more kinship with his elder brother Nassir (Karl Sarafidis), who is as passionately committed to his God of Islam as she is to her Catholic one. Those who’ve worshipped at French writer-director Bruno Dumont’s feet all along won’t need convincing, but for those who found early works like Humanité (1999) and Twentynine Palms (2003) unbearably ponderous and pretentious, Hadewijch is even more of an advance than 2006’s Flanders. It’s a quietly absorbing study of faith, fanaticism, and bottomless spiritual need. Visually handsome and accompanied (albeit sparsely) by J.S. Bach, it leaves the viewer plenty of moral and narrative ambiguities to chew on after the final fade. (1:45) Roxie. (Harvey)

Red Hill Like many recent westerns, Red Hill walks the line between genres. In fact, it’s more revenge thriller than a classic tale of gunslingers, which in the end is almost just as satisfying. True Blood‘s hunky Ryan Kwanten stars as the aptly named Shane Cooper, a young police officer assigned to a seemingly quiet country town. On his first day, he learns that his fellow officers have perhaps done something not-so-nice — and the victim of their not-so-niceness is seeking retribution. Look, there’s really nothing new here, aside from the nifty Australian accents. If you enjoy bloody vengeance (and who doesn’t?) you’ll likely get a kick out of Red Hill‘s brutal climax. But if you prefer your Westerns with a bit more depth, stick with Oscar contender True Grit. At the very least, Red Hill does a solid job of displaying Kwanten’s talents. Here’s hoping he picks up future roles that will leave a more lasting impression. (1:36) Lumiere. (Peitzman)

ONGOING

All Good Things This first narrative feature by Andrew Jarecki of the 2003 documentary Capturing the Friedmans fictionalizes another actual case of suspected nefarious deeds and high moral ambiguity. David Marks (Ryan Gosling) is the eldest son of a clan that’s among the greatest property-owning forces in NYC. But he rebels against following in the approved (and considerably corrupt) familial footsteps, in part by marrying Katie (Kirsten Dunst), a working-class Brooklynite whom his father (Frank Langella) helpfully notes “will never be one of us.” She’s no gold digger, however, and supports his every decision — even when he caves to pressure and joins the family biz after all, which is guaranteed to make him miserable. But does it make him crazy as well? The real-life model of this names-changed story was eventually accused or linked to three possible murders, though convinced only of one much lesser offense. All Good Things doesn’t feel the need to risk libel suits by pretending to know whether he was truly guilty or not — the record of known events alone over three-decades-plus offers quite enough provocative, sometimes downright bizarre fodder for drama. Very well-acted (particularly by Dunst, who’s been offscreen too long), the results have definite true-crime fascination. It’s too bad, however, that Jarecki evinces no talent for building suspense or momentum. What could have been a great movie just lays there after a certain point, absorbing on a moment-to moment basis yet ending up less than the sum of its parts. (1:41) Lumiere. (Harvey)

*Animal Kingdom More renowned for its gold rush history and Victorian terrace homes than its criminal communities, Melbourne, Australia gets put on the same gritty map as Martin Scorsese’s ’70s-era New York City and Quentin Tarantino’s ’90s Los Angeles with the advent of director-writer David Michôd’s masterful debut feature. The metropolis’ sun-blasted suburban homes, wood-paneled bedrooms, and bleached-bone streets acquire a chilling, slowly building power, as Michôd follows the life and death of the Cody clan through the eyes of its newest member, an unformed, ungainly teenager nicknamed J (James Frecheville). When J’s mother ODs, he’s tossed into the twisted arms of her family: the Kewpie doll-faced, too-close-for-comfort matriarch Smurf (Jacki Weaver), dead-eyed armed robber Pope (Ben Mendelsohn), Pope’s best friend Baz (Joel Edgerton), volatile younger brother and dealer Craig (Sullivan Stapleton), and baby bro Darren (Luke Ford). Learning to hide his responses to the escalating insanity surrounding the Codys’ war against the police — and the rest of the world — and finding respite with his girlfriend, Nicky (Laura Wheelwright), J becomes the focus of a cop (Guy Pearce) determined to take the Codys down — and discovers he’s going to have use all his cunning to survive in the jungle called home. Stunning performances abound — from Frecheville, who beautifully hides a growing awareness behind his character’s monolithic passivity, to the adorably scarifying Weaver — in this carefully, brilliantly detailed crime-family drama bound to land at the top of aficionados’ favored lineups, right alongside 1972’s The Godfather and 1986’s At Close Range and cult raves 1970’s Bloody Mama and 1974’s Big Bad Mama. (2:02) Opera Plaza. (Chun)

*Black Swan “Lose yourself,” ballet company head Thomas (Vincent Cassel) whispers to his leading lady, Nina (Natalie Portman), moments before she takes the stage. But Nina is already consumed with trying to find herself, and rarely has a journey of self-discovery been so unsettling. Set in New York City’s catty, competitive ballet world, Black Swan samples from earlier dance films (notably 1948’s The Red Shoes, but also 1977’s Suspiria, with a smidgen of 1995’s Showgirls), though director Darren Aronofsky is nothing if not his own visionary. Black Swan resembles his 2008 The Wrestler somewhat thematically, with its focus on the anguish of an athlete under ten tons of pressure, but it’s a stylistic 180. Gone is the gritty, stripped-down aesthetic used to depict a sad-sack strongman. Like Dario Argento’s 1977 horror fantasy, the gory, elegantly choreographed Black Swan is set in a hyper-constructed world, with stabbingly obvious color palettes (literally, white = good; black = evil) and dozens of mirrors emphasizing (over and over again) the film’s doppelgänger obsession. As Nina, Portman gives her most dynamic performance to date. In addition to the thespian fireworks required while playing a goin’-batshit character, she also nails the role’s considerable athletic demands. (1:50) California, Empire, 1000 Van Ness, Piedmont, Presidio, Sundance Kabuki. (Eddy)

Burlesque Burlesque really wants your love. Much like its heroine Ali, the small-town girl with showbiz dreams (and the not-so-secret pipes to make those dreams a reality), Burlesque knows all the moves by heart and is determined to land a spot in the chorus-line next to Cabaret (1972), Pretty Woman (1990), The Devil Wears Prada (2006), and Gypsy (1962). “Come on,” it implores, firing off Bob Fosse finger-snaps and leg-bearing kicks, “I’ve got Christina Aguilera as the plucky newcomer and Cher as the seasoned stage-vet and owner of the Burlesque Lounge, a kind of music video purgatory in which the Pussycat Dolls never broke up.” [snap snap snap] “I’ve got Stanley Tucci trapped in the makeover montage closet, again, as the sassy gay-in-waiting to both female leads.” [snap snap snap] “I’ve got girls gyrating in a Victoria’s Secret catalog worth of risqué underthings.” [snap snap pant] “I’ve got melisma!” [pant pant pant] “Did I mention Cher’s eleventh-hour power ballad?” Yes, it’s true. Burlesque has all of the above (and can’t you just hear the hunger in its voice?) And yet, it is afflicted by a particularly unfortunate kind of mediocrity. Not terrible enough to be redeemable as camp, Burlesque also lacks what Kay Thompson would call “bazazz” — none of the leads have any chemistry with each other, or the camera for that matter — to make this musical truly sing. In the words of many a casting agent: “Maybe next time, kid.” (1:48) SF Center, Shattuck. (Sussman)

Casino Jack An unfortunate curtain call for director George Hickenlooper, who died two months ago, this biopic about infamous Washington lobbyist Jack Abramoff — sprung from federal prison just in time for Xmas ’10 — is no more successful than his prior stab at Edie Sedgwick, 2006’s Factory Girl. He chooses to portray the real-life protagonist’s wild ride through the Bush years — buying politicians (notably Tom DeLay, who’s about to start his own prison term), screwing the “little guys” (like casino-owning Native tribes), furthering the conservative “values” agenda while pocketing a whole lotta $$$ — as a farcical Horatio Alger success story run amuck, not unlike recent The Informant! (2009) or Catch Me If You Can (2002). But neither script or handling are deft enough to pull that off, resulting in an irksomely broad cartoon of recent events that isn’t tough enough on the crimes and corruption at hand. Worse, the film — and in particular star Kevin Spacey (representing a rare occasion on which Hollywood’s substitute is less handsome than the figure portrayed) — at times seem to actually admire Abramoff as a ballsy, spunky, big swingin’-dick example of all-American go-getter-ness. Sure he’s got flaws, but ya gotta love a guy with such brass cojones, right? Wrong. Spacey is very showy here, misjudging his target such that he comes off an egomaniacal jerk playing an egomaniacal jerk. The film’s stylistic gambits (like its perky 60s vocal-ensemble score) are likewise smug ‘n’ snarky in ways more grating than clever. The one standout in a too-hardworking cast is Jon Lovitz as the sleaziest of all Abramoff’s sleazy-operator cronies; he knows how to go way over the top while maintaining precise, hilarious control. You’re better off seeing Alex Gibney’s recent doc Casino Jack and the United States of Money, which far more skillfully weighs this subject with commingled awe, sarcasm, and revulsion. (1:48) Embarcadero. (Harvey)

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader It’s no secret that C.S. Lewis’ Narnia saga is a big ol’ Christian allegory. And hey, that doesn’t mean it’s not entertaining. The film adaptations of his novels have been decent, in that they’ve worked to please both mainstream audiences and religious zealots who want to see the Jesus lion die for our sins. But while The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe (2005) and Prince Caspian (2008) were essentially passable, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is an overwhelming failure. It’s lazy, the plotting is uneven, the CGI is cringe-worthy, and the 3D is the kind of sloppy post-production mess that makes the actors’ faces look concave. Add to that the moral message, which is more hamfisted than ever. In his lengthy climactic sermon, Aslan — he’s known by a different name in our world — tells Lucy (Georgie Henley) and Edmund (Skandar Keynes) that all their adventures have been about bringing them closer to him. Suck it, atheists. (1:52) 1000 Van Ness, SF Center. (Peitzman)

*Fair Game Doug Liman’s film effectively dramatizes yet another disgraceful chapter from the last Presidential administration: how CIA agent Valerie Plame (Naomi Watts), who’d headed the Joint Task Force on Iraq investigating whether Saddam Hussein had WMDs, was identified by name in the Washington Post as a covert agent — thus ending her intelligence career and placing many of her subordinates and sources around the world in danger. This info was leaked to the press, it turned out, by highest-level White House officials as “punishment” for the New York Times editorial former ambassador Joe Wilson (Sean Penn) — Plame’s husband — wrote condemning their insistence on those WMDs to justify the Iraq invasion by then already well in progress. (The CIA task force had also found zero evidence of mass-destruction weapons, but Bush and co. chose to come up with their own bogus “facts” to sway US public opinion.) Purportedly, Karl Rove clucked to CNN’s Chris Matthews that Wilson’s awkwardly-timed dose of sobering truth rendered his spouse “fair game” for exposure. Unfortunately opening here several days after it might theoretically have done some election-day good — not that many Republican voters would likely be queuing up — Fair Game may be a familiar story to many. But its gist and details remain quite enough to make the blood boil. While the political aspects are expertly handled in thriller terms, the personal ones are a tad less successful. That’s partly because we never quite glimpse what brought these two very busy, business-first people together; but largely, alas, because so many of Wilson’s diatribes come off all too much as things that might be said by Sean Penn, Rabble-Rouser and Humanitarian. This is perhaps a case of casting so perfect it becomes a distracting fault. (1:46) Opera Plaza, Shattuck. (Harvey)

The Fighter Once enough of a contenda to have fought Sugar Ray Leonard — and won, though there are lingering questions about that verdict’s justice — Dicky (Christian Bale) is now a washed-up, crack-addicted mess whose hopes for a comeback seem just another expression of empty braggadocio. Ergo it has fallen to the younger brother he’s supposedly “training,” Micky (Mark Wahlberg), to endure the “managerial” expertise of their smothering-bullying ma (Melissa Leo) and float their large girl gang family of trigger-tempered sisters. That’s made even worse by the fact that they’ve gotten him nothing but chump fights in which he’s matched someone above his weight and skill class in order to boost the other boxer’s ranking. When Micky meets Charlene (Amy Adams), an ambitious type despite her current job as a bartender, this hardboiled new girlfriend insists the only way he can really get ahead is by ditching bad influences — meaning mom and Dicky, who take this shutout as a declaration of war. The fact-based script and David O. Russell’s direction do a good job lending grit and humor to what’s essentially a 1930s Warner Brothers melodrama — the kind that might have had Pat O’Brien as the “good” brother and James Cagney as the ne’er-do-well one who redeems himself by fadeout. Even if things do get increasingly formulaic (less 1980’s Raging Bull and more 1976’s Rocky), the memorable performances by Bale (going skeletal once again), Wahlberg (a limited actor ideally cast) and Leo (excellent as usual in an atypically brassy role) make this more than worthwhile. As for Adams, she’s just fine — but by now it’s hard to forget the too many cutesy parts she’s been typecast in since 2005’s Junebug. (1:54) Marina, 1000 Van Ness, SF Center, Sundance Kabuki. (Harvey)

*The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest If you enjoyed the first two films in the Millennium trilogy — 2009’sThe Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and The Girl Who Played With Fire — there’s a good chance you’ll also like The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest. Based on the final book in Stieg Larsson’s series, the film begins shortly after the violent events at the conclusion of the second movie. There are brief flashes of what happened — the cinematic equivalent of TV’s “previously on&ldots;” — but it’s likely an indecipherable jumble to Girl first-timers. Hornet’s Nest presents the trial of Lisbeth Salander (Noomi Rapace), the much-abused, much-misunderstood, entirely kick-ass protagonist of the series. With the help of journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist) and his sister Annika (Annika Hallin) as her lawyer, Lisbeth finally gets her day in court. The conspiracy that drives the story is somewhat convoluted, and while it all comes together in the end, Hornet’s Nest isn’t an easy film to digest. Still, it’s a well-made and satisfying conclusion to the trilogy — as long as you caught the beginning and middle, too. (2:28) Lumiere, Shattuck. (Peitzman)

Gulliver’s Travels Here are some things that happen in Gulliver’s Travels, the modernized 3D adaptation of Jonathan Swift’s classic tale. Lowly mailroom clerk Lemuel Gulliver (Jack Black) plagiarizes a bunch of travel guides and somehow manages to fool his travel editor crush Darcy (Amanda Peet), who immediately gives him a big on-location assignment. Gulliver ends up in the land of Lilliput, where one of the tiny inhabitants soon gets lost in Gulliver’s giant ass-crack. But he can do a lot of good for these people, like when he pees all over a burning building — in glorious yellow detail! — or teaches Princess Mary (Emily Blunt) to say, “boosh!” Of course, it’s not all fun and games! While Gulliver has the Lilliputians reenacting Guitar Hero, his enemy General Edward (Chris O’ Dowd) is building a giant robot to take the beast down. There is war on the horizon, but — spoiler alert — it’s nothing a group sing-a-long can’t solve. Look, if you still want to see Gulliver’s Travels, more power to you, but I assure you this review is no lazier than the film. (1:25) 1000 Van Ness. (Peitzman)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows — Part 1 As enjoyable as the Harry Potter films are for fans, they never really hold their own. And that’s OK. They’re not Oscar bait the way the Lord of the Rings movies were, but they’re competent adaptations of a much beloved book series. While Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows — Part 1 may not be a perfect film, it’s a solid translation of the source material, sure to appease the loyal readers who still can’t quite cope with the fact that the saga is nearly over. I count myself among them, and I’ll admit that it’s difficult to look at any Harry Potter movie with a critical eye. But even for an outsider, part one of Harry’s final chapter is likely to entertain, with plenty of action and a streamlined pace that helps the film move faster than past entries in the series. For devotees, the effect is greater, and the emotional wallop Deathly Hallows packs should not be underestimated. (2:26) 1000 Van Ness. (Peitzman)

How Do You Know With a title like How Do You Know, it’s amazing James L. Brooks’ latest romcom isn’t a total disaster. Don’t get me wrong, it’s bad — but there are one or two redeeming scenes that might justify a late-night cable viewing. Reese Witherspoon stars as Lisa, a professional softball player who gets cut from the Olympic team and has to figure out how to live life not as an athlete, but as a woman. If that sounds offensive, good: the most perplexing thing about How Do You Know is the way it reduces an otherwise strong female lead to traditional rom-com angst — will she choose cocky baseball star Matty (Owen Wilson) or the doting, hapless George (Paul Rudd)? Even when Lisa admits that she doesn’t think about settling down with a guy or having a baby, the film shoves her in that direction. Adding insult to injury, Jack Nicholson plays George’s dad Charles, padding out a corporate corruption side plot that stretches the movie to a plodding two hours. (1:53) 1000 Van Ness, Presidio, Sundance Kabuki. (Peitzman)

*I Love You Phillip Morris Given typically imitation-crazed Hollywood’s failure to built on the success of 2005’s Brokeback Mountain success — or see it as anything more than a fluke — the case of I Love You Phillip Morris is interesting for what it is and isn’t. It is, somewhat by default, the biggest onscreen gay romance (not including foreign and indie productions, which are always ahead of the curve) since that earlier film. What Phillip Morris is not, however, is a Hollywood or even American film, all appearances to the contrary. Its financing was primarily French — presumably because there wasn’t enough willing coin on this side of the Atlantic. We meet Steven Jay Russell as an uber-perky all-American lad — a nascent Jim Carrey. A near-fatal accident, however, induces him to merrily chuck it all and live life to the fullest by moving from Georgia to South Beach and becoming a “big fag.” He soon discovers that “being gay is really expensive,” or at least his chosen A-lister lifestyle is, so he turns to crime as a means of support. During one hoosegow stay, he meets the non-tobacco-related Phillip Morris (McGregor), a sweet Southern sissy. Directors Glenn Ficarra and John Requa approach their fascinating material with brashness and some skill, but without the control to balance its steep tonal shifts. Surprisingly, it’s in the “love” part that they often succeed best. While their comic aspects sometimes tip into shrill, destabilizing caricature — the excess that brilliant but barely-manageable Carrey will always drift toward unless tightly leashed — this movie’s link to Brokeback is that it never makes the love between two men look inherently ridiculous, as nearly all mainstream comedies now do to get a cheap throwaway laugh or three. (1:38) Shattuck. (Harvey)

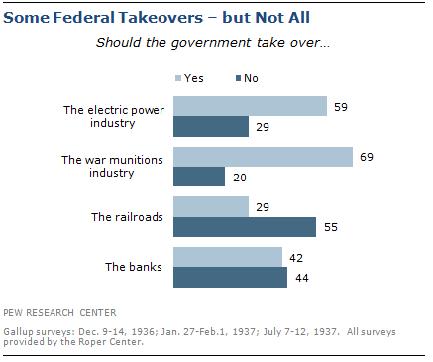

Inside Job Inside Job is director Charles Ferguson’s second investigative documentary after his 2007 analysis of the Iraq War, No End in Sight, but it feels more like the follow-up to Alex Gibney’s Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005). Keeping with the law of sequels, more shit blows up the second time around. As with No End in Sight, Ferguson adeptly packages a broad overview of complex events in two hours, respecting the audience’s intelligence while making sure to explain securities exchanges, derivatives, and leveraging laws in clear English (doubly important when so many Wall Street executives hide behind the intricacy of markets). The revolving door between banks, government, and academia is the key to Inside Job‘s account of financial deregulation. At times borrowing heist-film conventions (it is called Inside Job, after all), Ferguson keeps the primary players in view throughout his history so that the eventual meltdown seems anything but an accident. The filmmaker’s relentless focus on the insiders isn’t foolproof; tarring Ben Bernanke, Henry Paulson, and Timothy Geithner as “made” guys, for example, isn’t a substitute for evaluating their varied performances over the last two years. Inside Job makes it seem that the entire crisis was caused by the financial sector’s bad behavior, and this too is reductive. Furthermore, Ferguson does not come to terms with the politicized nature of the economic fallout. In Inside Job, there are only two kinds of people: those who get it and those who refuse to. The political reality is considerably more contentious. (2:00) Clay, Shattuck. (Goldberg)

The King’s Speech Films like The King’s Speech have filled a certain notion of “prestige” cinema since the 1910s: historical themes, fully-clothed romance, high dramatics, star turns, a little political intrigue, sumptuous dress, and a vicarious taste of how the fabulously rich, famous, and powerful once lived. At its best, this so-called Masterpiece Theatre moviemaking can transcend formula — at its less-than-best, however, these movies sell complacency, in both style and content. In The King’s Speech, Colin Firth plays King George VI, forced onto the throne his favored older brother Edward abandoned. This was especially traumatic because George’s severe stammer made public address tortuous. Enter matey Australian émigré Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush, mercifully controlled), a speech therapist whose unconventional methods include insisting his royal client treat him as an equal. This ultimately frees not only the king’s tongue, but his heart — you see, he’s never had anyone before to confide in that daddy (Michael Gambon as George V) didn’t love him enough. Aww. David Seidler’s conventionally inspirational script and BBC miniseries veteran Tom Hooper’s direction deliver the expected goods — dignity on wry, wee orgasms of aesthetic tastefulness, much stiff-upper-lippage — at a stately promenade pace. Firth, so good in the uneven A Single Man last year, is perfect in this rock-steadier vehicle. Yet he never surprises us; role, actor, and movie are on a leash tight enough to limit airflow. (1:58) Albany, Embarcadero, Empire, 1000 Van Ness, Piedmont, Sundance Kabuki. (Harvey)

Little Fockers (1:50) Four Star, Marina, 1000 Van Ness, Shattuck.

Love and Other Drugs Whatever kind of movie you think Love and Other Drugs is, you’re wrong. To be fair, it’s hard to pin down. This is a romantic comedy about two people who can’t commit, a serious drama about a young women living with Parkinson’s, a dark satirical look at the pharmaceutical industry, and — well, you get the idea. Love and Other Drugs shouldn’t work, really: the story is overstuffed and the script isn’t always cohesive. But leads Jake Gyllenhaal and Anne Hathaway sell the material well. In the end, it almost doesn’t matter that the film isn’t sure what it wants to be. “Almost” is key: there are moments in which Love and Other Drugs slips into Judd Apatow comedy territory, and others when it completely devolves into a sexual farce. It works on several different levels, but all together, it’s admittedly a bit of a mess. No bother. Just focus on the attractive naked people making out and you’ll likely enjoy the movie regardless. (1:53) Elmwood, SF Center. (Peitzman)

*Made in Dagenham I hesitate to use the word “spunky,” lest I sound condescending, but indeed that’s what we have here: the spunky tale, drawn from real life, of women who worked sewing seats at a British Ford factory in the late 60s — and fought for equal pay, despite the tide of sexism that desperately tried to hold them down. Heading the charge is Rita (Sally Hawkins from 2008’s Happy-Go-Lucky), a married mom who becomes a feminist icon (and a labor hero) without really meaning to; she’s the most developed character in a script that mostly calls forth types (Bob Hoskins as the encouraging union man; Rosamund Pike as the frustrated intellectual-turned-housewife; Rita’s slutty factory co-worker with the enormous beehive; steely-eyed Ford execs). Adding spark is Miranda Richardson as Britain’s no-nonsense Secretary of State Barbara Castle, a legendary Labour party politician. Though it’s packaged a bit too neatly — from frame one, the film’s peppy tone all but guarantees a happy ending — Made in Dagenham‘s message is uplifting and worthy, and a reminder that it wasn’t so long ago that women were fighting for the seemingly most obvious of rights. (1:53) Opera Plaza, Shattuck. (Eddy)

127 Hours After the large-scale, Oscar-draped triumph of 2008’s Slumdog Millionaire, 127 Hours might seem starkly minimalist — if director Danny Boyle weren’t allergic to such terms. Based on Aron Ralston’s memoir Between a Rock and a Hard Place, it’s a tale defined by tight quarters, minimal “action,” and maximum peril: man gets pinned by rock in the middle of nowhere, must somehow free himself or die. More precisely, in 2003 experienced trekker Ralston biked and hiked into Utah’s Blue John Canyon, falling into a crevasse when a boulder gave way under his feet. He landed unharmed … save a right arm pinioned by a rock too securely wedged, solid, and heavy to budge. He’d told no one where he’d gone for the weekend; dehydration death was far more likely than being found. For those few who haven’t heard how he escaped this predicament, suffice it to say the solution was uniquely unpleasant enough to make the national news (and launch a motivational-speaking career). Opinions vary about the book. It’s well written, an undeniably amazing story, but some folks just don’t like him. Still, subject and interpreter match up better than one might expect, mostly because there are lengthy periods when the film simply has to let James Franco, as Ralston, command our full attention. This actor, who has reached the verge of major stardom as a chameleon rather than a personality, has no trouble making Ralston’s plight sympathetic, alarming, poignant, and funny by turns. His protagonist is good-natured, self-deprecating, not tangibly deep but incredibly resourceful. Probably just like the real-life Ralston, only a tad more appealing, less legend-in-his-own-mind — a typical movie cheat to be grateful for here. (1:30) Bridge, Shattuck. (Harvey)

*Rabbit Hole If Rabbit Hole doesn’t sound like the kind of movie you’d want to watch, I don’t blame you. Following the lives of a married couple dealing with the loss of their young son, the film sounds a lot like the kind of Lifetime movie you accidentally spend a hung over Sunday sniffling through. But Rabbit Hole is a smart, complex addition to the genre, with exceptional performances from leads Nicole Kidman (Becca) and Aaron Eckhart (Howie), and a script by David Lindsay-Abaire, adapting his Pulitzer Prize-winning play. Director John Cameron Mitchell infuses Rabbit Hole with his trademark dark humor, creating a film that understands the serious toll grief takes but isn’t afraid to step back and laugh at life, too. Special attention must also be paid to the supporting cast, including Dianne Wiest as Becca’s mother, and newcomer Miles Teller as Jason. Explaining Jason’s role would be giving away too much — it’s enough to say that his presence is part of what elevates Rabbit Hole from grief porn to one of this year’s best. (1:32) Embarcadero. (Peitzman)

Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale High in the Finnish Arctic a scientific excavation unearths something exceedingly peculiar, with results that include several violent adult deaths and the mysterious disappearance of all local children in a depressed community whose flagging major industry is a reindeer slaughterhouse. When the area’s arms-bearing, beer-swilling menfolk prove clueless, it falls to hardboiled eight-year-old Pietari (Onni Tommila) to turn Kick-Ass and precociously marshal a full-on strategic offensive against intruders who reveal a disturbing ancient truth about Santa Claus and his elves. Writer-director Jalmari Helender’s first feature (which expands upon a couple prior shorts’ premise) gets points for being something definitely offbeat in the Yuletide fantasy sweepstakes. That said, its mix of black comedy, near-horror and action adventure doesn’t quite gel, or add up to more than an absurdist joke that feels overtaxed even at a fairly trim 84 minutes. (1:42) Lumiere, Shattuck. (Harvey)

*The Social Network David Fincher’s The Social Network is a gripping and entertaining account of how Facebook came to take over the known social-networking universe. In this version of events — scripted by Aaron Sorkin and based on Ben Mezrich’s book The Accidental Billionaires, in turn based substantially on interviews with FB cofounder Eduardo Saverin, with input from Mark Zuckerberg icily absent — a girlfriend’s dumping of Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) on a crisp evening in 2003 is the impetus in his headlong quest for a “big idea.” The film is structured around the conference-room depositions for two separate lawsuits, brought against Zuckerberg by Saverin (Andrew Garfield) and by fellow Harvard entrepreneurs Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss (Armie Hammer) and Divya Narendra (Max Minghella) for crimes involving intellectual property and vast scads of retributive money. Unless Zuckerberg decides to post it on Facebook (which he probably shouldn’t, given the nondisclosure vows that capped off the first round of lawsuits), we’ll never know what truly motivated him and how badly he screwed over his friends and fellow students. But Fincher and Sorkin have crafted a compelling, absorbing, and occasionally poignant tale of how it could have happened. (2:00) Shattuck. (Rapoport)

Somewhere A lonely Ferrari zooms around a deserted track, over and over and over again. The opening scene of Sofia Coppola’s latest, Somewhere, is such an obvious metaphor that at first I thought the director was joking. Actually, she’s not: Somewhere is indeed a repetitous movie about a very boring, very ennui-laden individual, who happens to be a movie star with the marquee-ready name of Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff). Now that you’ve been smacked over the head with metaphor, feel free to play spot the subtext: Johnny lives at Sunset Boulevard haunt the Chateau Marmont, legendary for its often-behaving-badly celebrity clientele. His life is an endless progression of blah (wake up, smoke, pop a Propecia, eyefuck and fuck random female admirers), broken up by job obligations — the tedium of a press conference here, the drudgery of a visit to the special-effects make-up studio there. Sigh. Would any director not as privileged as Coppola dare to focus on a character whose massive wealth can’t at all assuage his existential crisis? Money may not buy happiness, but it’s kind of hard to feel sorry for a guy whose depression plays out as he floats the day away at a luxury hotel. Fortunately, there is a bright spot in all this: mostly-absentee dad Johnny has a kid, Cleo, a tween sprite played by the charming Elle Fanning. Cleo is the only meaningful thing in Johnny’s life, and the only interesting thing that happens in this glacially-paced, bellybutton-obsessed movie. (1:38) SF Center. (Eddy)

Summer Wars Teenage mega-nerd Kenji is a mathematical genius, already employed as an admin by Oz, a global virtual-reality program that’s kind of what Facebook will probably become in a few years — a place where everyone on the planet maintains an avatar, and carries on all of their necessary and unnecessary business, from city management to mortal combat. Basically, Oz won the internet. You might think Summer Wars, a rather charming animated tale from Japanese director Mamoru Hosoda, would make Oz the villain in this tale, but instead, it’s a rogue AI program that brings the online world to its knees with increasingly dangerous mischief. Kenji’s role in this virtual-reality disaster is complicated by the fact that in the real world, he’s been cajoled into pretending to be his crush’s boyfriend during an extended-family reunion at her great-grandmother’s estate. Fortunately, the expected clichés that come with this subplot are forgivable, since most of Summer Wars is comprised of enjoyable original ideas, with delightful animation to boot. (1:53) Opera Plaza. (Eddy)

Tangled In its original form, Rapunzel‘s a pretty brutal fairy tale: barely pubescent girl gets knocked up by a prince — who’s then blinded by her evil witch guardian — leaving Rapunzel to fend for herself as she’s exiled into the desert and bears twins. Relax, that isn’t the story Tangled tells. The new Disney film is a complete revamping of the tale: Rapunzel (Mandy Moore) escapes the clutches of Mother Gothel (Donna Murphy) with the help of ne’er-do-well Flynn Ryder (Zachary Levi). Along the way, there are songs and slapstick moments and, yes, anthropomorphic animals. But unlike the classic feel of last year’s The Princess and the Frog, Tangled comes across as recycled. It’s just not as fresh and sharp as it should be, especially given recent Disney accomplishments like Toy Story 3. Kids will enjoy it and adults won’t be bored, but it’s a step backward for the House of Mouse. And don’t expect to be humming any of the songs after you exit the theater. (1:32) Elmwood, 1000 Van Ness, SF Center. (Peitzman)

*Tiny Furniture Aura (Lena Dunham) has returned home to Manhattan after four undergraduate years cocooning in a Midwestern liberal arts education; either big-city life has gotten harder, or she has gotten very soft. She’s rather reluctantly welcomed back into their blindingly white TriBeCa loft by a successful artist mother (Laurie Simmons) and caustic, ambitious younger sister (Grace Dunham). Neither seemed to miss her much, and both are played by the writer-director-star’s actual family members. “I don’t know what to do with my life” is a very typical state post-graduation, but Aura’s stasis is positively Oblomov-ian — and since she is our protagonist, this movie, too, is all about the comedy of rudderlessness. Recently abandoned by a feminist college boyfriend who needed to “find himself,” she tries glomming on to such dubious romantic prospects as visiting filmmaker Jed (Alex Karpovsky), who gladly accepts free room and board but barely seems to register her as female. “Best friend” Charlotte (Jemima Kirke) is a spectacular wellspring of ideas meant to improve Aura’s lot, though since Aura basically walks around with a “Kick Me” sign on her posterior and Charlotte is sexy, moneyed, endlessly entitled trainwreck, her advice (e.g. “Just take him somewhere and grab his cock”) are bound make things worse. Tiny Furniture is indeed small, as first-feature achievements go. It’s anyone’s guess whether Dunham has it in her to make good movies less baldly autobiographical, as she’ll need to if she wants to have a career. That said, few films — certainly nothing Woody Allen’s done for ages — have been so dryly hilarious about the kind of NYC art-social milieux in which being a nobody really, truly sucks. Because everyone else is already somebody, if only in their own minds. It also has, hands down, the greatest three-minute, single-shot whiny meltdown speech of 2010 or nearly any other year. (1:38) Shattuck. (Harvey)

The Tourist Ah, all the champagne wishes and caviar dreams and daydreams of bouncing truffles off Angelina Jolie’s pillowy pout couldn’t quite stop The Tourist from going very much astray. How many ways can a movie go wrong? There’s the by-the-numbers yet somehow directionless direction from filmmaker Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, who made one of the most absorbing film about surveillance to date with The Lives of Others (2006), only to completely miss the mark with this tone-deaf attempt at a Charade-like romantic escapade. The musty, fussy bodice-swelling score by James Newton Howard. A glassy-eyed Jolie somehow mistaking stony inexpressiveness for Garbo-esque mystique? The list goes on — at core, the casting is perhaps the sole compelling reason to see this waxy, museum-piece remake of the French film Anthony Zimmer (2005) — though the chemistry is negligible between the film’ attractive stars, with Jolie in particular waltzing through like a beautiful Euro-zombie, seemingly intent on sleepwalking through Venice and saving her better efforts for a more socially conscious film. Her disdain for the material sucks the air from this entire enterprise. The only bit of un-snuffable charm here lies in Johnny Depp’s naifish delivery and the murky, ironic humor he unobtrusively layers into his bemused performance. But then he’s just a tourist, passing through and providing the only scrap of pleasure in an otherwise dull outing. (1:44) 1000 Van Ness, Presidio, Shattuck, Sundance Kabuki. (Chun)

Tron: Legacy A rare sequel among remakes, Tron: Legacy remains true to the 1982 nerd cult classic: it’s essentially a silly movie about being transported into a computer world where everyone dresses in rave couture. Jeff Bridges returns, now in opposing roles. On one side he’s computer genius Kevin Flynn, bearded zen master, and across the uncanny valley he’s CLU, an ageless software lord. Flynn’s been stuck in the Matri…er…Grid for decades, as CLU followed his programming to its logical conclusion: genocide. This is a bit too heavy of a theme for a film where almost every character gets blown to bytes upon introduction (cough, Michael Sheen, cough) but the light cycles and death pong are really cool in 3D. The plot, when it’s not setting up Disney’s inevitable sequels (hello, pointless Cillian Murphy) is Star Wars (1977), except Obi-wan Lebowski is the father. The son is Sam (Garrett Hedlund), whose good looks, penchant for extreme sports, and vacuous personality are the perfect avatar for our geek fantasy, where women strip us bare and are sexy guard dogs (Olivia Wilde.) While not passing the Bechdel Test, the film may be worth admission to hear the Dude’s Jedi utter “It’s biodigital jazz, man!” Look out for a special cameo by Daft Punk, playing hits from its score, which sounds like Kraftwerk mixing Vangelis and Danny Elfman (available in stores now.) They’ll be the ones wearing helmets. No, the other ones. (2:05) 1000 Van Ness, Sundance Kabuki. (Prendiville)

*True Grit Jeff Bridges fans, resist the urge to see your Dude in computer-trippy 3D and make True Grit your holiday movie of choice. Directors Ethan and Joel Coen revisit (with characteristic oddball touches) the 1968 Charles Portis novel that already spawned a now-classic 1969 film, which earned John Wayne an Oscar for his turn as gruff U.S. Marshall Rooster Cogburn. (The all-star cast also included Dennis Hopper, Glen Campbell, Robert Duvall, and Strother Martin.) Into Wayne’s ten-gallon shoes steps an exceptionally crusty Bridges, whose banter with rival bounty hunter La Boeuf (a spot-on Matt Damon) and relationship with young Mattie Ross (poised newcomer Hailee Steinfeld) — who hires him to find the man who killed her father — likely won’t win the recently Oscar’d actor another statuette, but that doesn’t mean True Grit isn’t thoroughly entertaining. Josh Brolin and a barely-recognizable Barry Pepper round out a cast that’s fully committed to honoring two timeless American genres: Western and Coen. (1:50) California, Empire, 1000 Van Ness, Presidio, SF Center, Sundance Kabuki. (Eddy)

*White Material Claire Denis was raised in colonial Africa, and White Material is her third feature set in its wake (the first two were 1988’s Chocolat and 1999’s breathtaking Beau Travail). This new film is very much about Africa, compositing elements of several different “troubles” (child soldiers, a strong man’s militia, radio broadcasts fomenting violence) into an abstract of conflict. Between the dead-eyed rebels in the bush and the brutally efficient forces in town stands Maria Vial (Isabelle Huppert), a colonial holdout. As the troubles mount, Maria buries the signs of encroaching threats; her refusal to be terrorized is a trait we typically ascribe to male action heroes, though Maria’s resolute blindness is its own kind of privilege in the African context. Unusually for Denis, the film is both a literary adaptation (cowritten with author Marie NDiaye and based on Doris Lessing’s The Grass is Singing) and a star vehicle for Huppert, whose stringy musculature is a nice match for Yves Cape’s lithe camerawork. The idea of Maria’s character already tends toward the parabolic, though, and all these different inputs can result in too much dramatic underlining. But for all White Material‘s novelistic concessions, Denis’ subtle command of composition and rhythm as elements of narration is beyond doubt. Her use of the handheld camera remains preternaturally attuned to her characters’ pleasures and anxieties. (1:42) Opera Plaza. (Goldberg)

Yogi Bear (1:19) 1000 Van Ness.