arts@sfbg.com

FILM At a moment when gay people and gay rights have never been more prominent — from the escalating numbers of states and countries permitting gay marriage to the controversy over Olympics-hosting Russia’s murky new anti-gay legislation — it’s hard to imagine the climate in which Portrait of Jason premiered in late 1967. The “new permissiveness” was just beginning to impact American cinema; soon there would be a small vogue of mainstream films addressing homosexuality in one way or another. But they would mostly be condescending, tragic, hostile and/or grotesquely comedic — you could argue there wasn’t a truly sympathetic Hollywood feature about a non-stereotypical gay relationship until 1982’s Making Love. (Which flopped, despite all publicity, and encouraged no imitations.)

Today it’s a common complaint that them perverts are too damn omnipresent in the news, on TV, everywhere — their heightened public profile somehow violating the “rights” of others to ignore or hate on them. But nearly half a century ago, Shirley Clarke’s documentary “portrait” of one rather flaming real-life personality — not just gay, but African American, too — seemed unprecedentedly exotic. No less than then-Supreme God of All Cinema (and supremely heterosexual) Ingmar Bergman called it “the most extraordinary film I’ve ever seen in my life … absolutely fascinating.” He probably found mankind’s first moon landing two years later less startling.

The latest in Milestone Films’ “Project Shirley” series of restored Clarke re-releases, Portrait of Jason can’t be experienced that way now. Any surviving exoticism is now related to the subject’s defining a certain pre-Stonewall camp persona, and the movie’s reflecting a 1960s cinema vérité style of which its director was a major proponent. Perhaps influenced by fellow New Yorker Andy Warhol’s early films, the setup couldn’t be simpler: instead of staring at the Empire State Building or somebody sleeping for X number of hours, we spend 12 hours in the company of Jason Holliday, née Aaron Payne. (He explains someone named Sabu in San Francisco during his “three, four, five years” there “was changing people’s names to suit their personality,” adding “San Francisco is a place to be created, believe me.”)

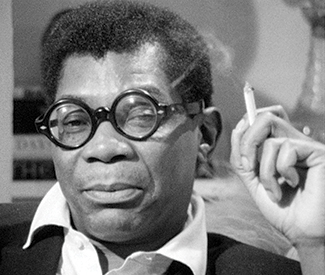

Or rather Clarke and her then-partner, actor Carl Lee, spend those hours — from 9 pm to 9 am — with Jason, while we get a 107-minute distillation. Nattily attired, waving a cigarette around while downing an epic lineup of cocktails, Jason is a natural performer who relishes this filmic showcase as “my moment.” No matter what, he says, he will now “have one beautiful something that is my own.”

At first Clarke and Lee simply let him riff, prompting him to speak calculated outrages they’ve probably already heard. (“What do you do for a living, Jason?” “I’m a … I’m a stone whore. And I’m not ashamed of it.”) He seems to be trying out material for a nightclub act that’s part Lenny Bruce, part snap diva. “I guess I’m a male bitch, because I have a tendency to go around and unglue people. I’ve spent so much of my time bein’ sexy I haven’t gotten anything else done. I’ve been balling from Maine to Mexico.” He shares anecdotes of working as a “houseboy” for rich white women during his in SF; he dons ladies’ hats and a feather boa to do imitations of Scarlett O’Hara, Miss Prissy, Katharine Hepburn, and Carmen Jones.

He’s indeed the life of his own party — increasingly smashed as wee hours encroach in Clarke’s Chelsea Hotel room — but there’s a certain desperation to this act that she and particularly Lee eventually pounce on. The exact nature of the two men’s relationship intrigues once Lee starts goading Jason to cut the “bullshit” and pony up some truths. “We know you’re a big con artist and you don’t really give a shit about nothin’ and nobody,” the off-camera Lee barks, later referencing some “dirty lies” Jason had allegedly spread about him.

By the time the former is calling the latter a “fuckin’ nasty bitch,” the film has become a queasy mix of exploitation and collusion. “Nervous and guilty and simple as I am,” Jason has a braggadocio that camouflages a self-loathing he’s just as willing to expose. When actual tears-of-a-clown are shed, the filmmakers seem cruel. Still, the “portrait” is incomplete — Clarke and Lee don’t press their subject to explicate the past spousal abuse, suicide attempt, and “nuthouse” and jail stays he drops into conversation as casually as he mentions a friendship with Miles Davis.

Two years later Yoko Ono and John Lennon would film the extremely disturbing Rape — 77 minutes of a camera crew silently, aggressively following an increasingly bewildered and panicked young woman around Manhattan, reducing her to a whimpering wreck. It was a human experiment in the name of art as striking as it was sadistic. While less traumatic, Portrait of Jason also stretches a very 1960s notion of cinema-as-angry-analyst’s-couch to uncomfortable lengths.

Clarke, who died in 1997 — one year before Jason — remains a fascinating, underappreciated figure who suffered all the consequences of being a stubbornly individual filmmaker in an era when women directors were rare and little-respected. (Not that that’s changed greatly since.) Switching from dance to movies in the ’50s, she earned an Oscar nomination for a 1960 short, then won one outright for a 1963 documentary about poet Robert Frost. Yet her career was constantly stymied, finally forcing her into academia. French director Agnès Varda’s 1969 curio Lions Love has her playing herself, a matter-of-fact New Yorker baffled equally by the Hollywood industry she’s trying to enter and by the upscale hippie ménage à trois antics of her hosts, Warhol star Viva and Hair co-creators Gerome Ragni and James Rado.

PORTRAIT OF JASON opens Fri/16 at the Roxie.