arts@sfbg.com

YEAR IN FILM Two of 2012’s finest, most philosophical, and most frustrating movies share a setting of sorts. Although one film takes place in New York, the other in Paris, both films’ protagonists spend a lot of time in their white stretch limousines. The limo: an ostentatious symbol of status and wealth, a home away from home.

In David Cronenberg’s unsettling Don DeLillo adaptation Cosmopolis, it’s superwealthy magnate Eric Packer (a defanged Robert Pattinson) who eats, fucks, and talks business in a limo, trapped in ever-worsening NYC traffic. For Monsieur Oscar (Denis Lavant) in Leos Carax’s Holy Motors, the limousine is also place of business. When I first saw Holy Motors, I noted the “limo-as-liminal-space” — Oscar’s limousine is his dressing room, a place of transformation for the chameleonic arch-performer.

>>Read more from our Year in Film 2012 issue here.

This common factor, though coincidental, is not accidental. The limousine as symbol and space is crucial to the structure of both films, which I’ve taken half-facetiously to calling “limo operas.” In both, white stretch limos are distinctive cells in the secret circulatory system of late capitalist society. Their passengers have a privileged viewpoint — they can see out, but others can’t see in. When the camera joins the passengers inside the limo, the city becomes an almost unreal backdrop for the private activities within.

In Cosmopolis, there’s an ongoing, ambivalent dialogue about the dispersal of all things into data; everything is getting smaller, faster, swept away by the flow of “cyber-capital.” But Eric Packer, whose vast wealth is about to collapse due to minute changes in the value of the yuan, is obsessed with large, worldly purchases. He has two private elevators with specialized soundtracks, and a Soviet bomber plane that he keeps in a hangar. He’s insistent that he wants to buy the Rothko Chapel, despite its nature as a public artwork. And he describes his limo as a car sawed in half and expanded. He’s had his limo “Prousted” — lined with soundproof cork like Marcel Proust’s bedroom — which he describes as “a gesture … a thing a man does.” The soundproofing doesn’t work, though. His limousine is a performance of his ego, and of its futility.

It’s also an object in the movie’s central dialogue about systems that operate beyond perception. Much like units of encrypted economic information, limos push through the city announcing the self-importance of their passengers. They might be carrying a president or a celebrity, but one of Packer’s employees reminds him that limos also connote “kids on prom night, or some dumb wedding.” And then they go away. Packer asks, “Where do all these limos go at night?” and he finally gets an answer from his limo driver — there are underground garages — they slumber beneath the city. Even his driver’s description of the garages reinforces the weird information-value of the vehicle — “a marketplace of limos.”

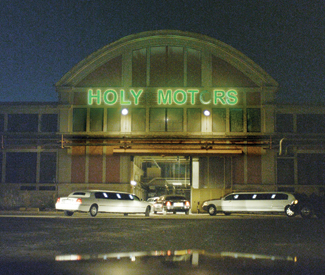

Oscar’s limo in Holy Motors is perhaps less of a grand statement to the public, but it’s still a sort of grandiose contradiction on wheels. Oscar is an actor who fulfills “appointments” — enigmatic, prearranged convergences with other lives, where he transmutes into elaborately conceived new beings, for an audience of no one and everyone. When another strange figure, the critic to Oscar’s artist, appears in the limo, Oscar explains his less convincing performances as a result of technological progress: “I miss the cameras. They used to be heavier than us. Then they became smaller than our heads. Now you can’t see them at all.” And so he prepares for his appointments in an eminently visible, garishly substantial machine. In the world of Holy Motors, white stretch limos are apparently markers of Oscar’s trade — when his limo collides with another, it is coincidentally also carrying a performer, his old flame, en route to her own appointment.

In contrast to Cosmopolis, Carax’s film gives a glimpse inside the occluded space of the garage where limos sleep — literally. In its amusing and crucial final scene, Holy Motors returns to the titular motor pool, and eavesdrops on the after-hours gossiping of an entire fleet of sentient limousines. One laments that they’ll soon all be junked, and another agrees: “Men don’t want visible machines anymore.” But visible machines are precisely what Oscar wants, so he makes his office in a limo.

Both Packer and Oscar are aging, battling obsolescence while stubbornly clinging to old operating procedures. In these two films, deeply entrenched in commenting on the withering progress of postmodern life, the stretch limo is a loud, defiant holdout. You might even call it a relic — it is, after all, a holy motor. *

Read more from Sam Stander at hellascreen.blogspot.com

SAM STANDER’S TOP 15 OF 2012

1. Margaret (Kenneth Lonergan, US, 2011)

2. The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky, Hungary/France/Germany/Switzerland/US, 2011)

3. Cosmopolis (David Cronenberg, Canada/France/Portugal/Italy)

4. Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson, US)

5-6. [tie] Cabin in the Woods (Drew Goddard, US, 2011)/The Avengers (Joss Whedon, US)

7-8. [tie] Haywire (Steven Soderbergh, US/Ireland, 2011)/Magic Mike (Steven Soderbergh, US)

9. Whores’ Glory (Michael Glawogger, Germany/Austria, 2011)

10. Holy Motors (Leos Carax, France/Germany)

11. Pina (Wim Wenders, Germany/France/UK, 2011)

12. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, US)

13. The Color Wheel (Alex Ross Perry, US, 2011) 14. This Is Not A Film (Jafar Panahi, Iran, 2011) 15. Kill List (Ben Wheatley, UK, 2011)