arts@sfbg.com

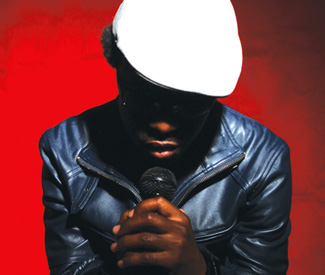

MUSIC One day in November 2004, my then-girlfriend returned to our Oakland apartment all excited. “I just heard this on KMEL,” she said. She handed me a CD, Baby Jaymes, Ghetto Retro (Underground Soul), while she unwrapped the included Ghetto Retro EP and cued up “Nice Girl.” “He sounds like Prince,” she enthused—we were Prince geeks—”but he’s from East Oakland!”

Something in the way the vocals were layered, the tasty guitar and bass details under aloof keyboards, and the idiosyncratic, non-pimp, non-player personality that disclosed itself seemed to justify the comparison, particularly as we moved on to the LP. The hidden track “Ev’ry Nuance,” for example, could be a Lovesexy outtake, even as its more lo-fi aesthetic seemed to allude knowingly to 1999-era bootlegs.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YJrO8GoozIE

Comparisons to Prince would be made in nearly every review of Ghetto Retro, though the insistence was a little misleading. While Prince is definitely an influence, BJ — as he’s known — isn’t especially well-versed in the Purple One’s catalog. Some of the resemblance stems from the common influence of 1960s and ’70s soul; Motown, particularly Smokey Robinson, and Stax loom much larger for Baby Jaymes, and in many ways, the similarly pint-sized singer is the anti-Prince, possessing no conventional technical musical ability, depending on collaborators to translate the melodies and arrangements he hears in his head.

In 2007, I had the experience of watching him cajole a string trio from blank incomprehension into a soaring, unscripted overdub reminiscent of a Paul Riser classic. Yet I’ve also seen the comparatively simple matter of a guitar overdub founder for want of a common vocabulary.

“It’s all about energy to me,” BJ says, “but I can’t always articulate it in a way that musicians understand. But if I articulate it emotionally they might be like, yes! and we’re there. I used to knock myself out because I can’t play, but that’s part of my gift. I’ve gotten to the place where I’m ok with that.”

The other major difference is the difference between Minneapolis and East Oakland, for while Prince has profoundly influenced hip-hop, he’s never known what to do with it, whereas it’s second nature to BJ, hailing from the notorious Rollin’ 100s (99th and MacArthur, to be exact).

Much of Ghetto Retro is built on heavily manipulated samples, augmented with instruments, and though he’s the furthest thing from a thug — I’ve never heard him cuss, though I have heard him say “my goodness” and even “golly”—Baby Jaymes sounds entirely natural with Turf Talk on his 2008 single “The Bizness” or The Jacka on his new EP, Whatever Happened to Baby Jaymes?, released late last year on Hiero-imprint Clear Label Records.

THE SHIFT

The EP’s title, BJ admits, was the brainchild of Souls of Mischief and Hieroglyphics member and Clear Label head Tajai Massey, both punning off the Bette Davis film and nodding to the seven-year wait since Ghetto Retro. BJ initially resisted.

“I disappeared,” he admits. “But I don’t want people to think I wasn’t doing anything.”

“I was bummed out with the artist thing,” he continues. “People remember me — which is a good thing. But I couldn’t imagine life not having anonymity. To this day I can’t go anywhere in the Town without seeing at least one person that knows me. It can be overwhelming.”

BJ’s local profile, elevated by airplay on KMEL, national press from Fader and XLR8R, and even a 2005 GOLDIE, was complicated by the chronic difficulty of making money as a Bay Area urban artist. In the mid-’00s, besides longstanding major label distinterest, Bay Area independent artists suddenly saw their financial foundations crumble with the decline of CD sales.

“You have to preserve your mystique,” he says, “but you don’t have money to be that guy all the time. I might really be on the bus and you see me on the bus and it just kills my whole thing for you. So I decided I just wanted to make music, not make music to be famous.”

Instead BJ moved to L.A. to pursue licensing deals in movies and TV. Even before Ghetto Retro, he’d already tapped into Hollywood money, writing a song (“Without a Daddy” by Touché) that appears in Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday (1999). (His own version appears on Ghetto Retro as “Black Girl/White Girl.”) Since relocating, he’s racked up an oddball assortment of screen credits, from a few seconds of music in a Nicole Kidman vehicle (2007’s The Invasion) to production work on Fox’s intro to the 2008-09 NFC Championship broadcast (apparently Cleatus the Robot’s first foray into hip-hop).

More recently NCIS used a snippet “so small and incidental, you can barely hear it,” but this brings in incomparably more money than dropping a Bay Area hip-hop soul classic. Essentially BJ makes the bulk of his modest income off five song placements and would like to bring that number up to around 40 reliable ones, which he estimates would bring in a comfortable enough existence to fulfill his artistic ambitions.

THE PROVERBIAL RETURN

For, despite his earlier discomfort, Baby Jaymes’s artistic ambitions remain, and Tajai was able to induce him to sign to Clear Label to record a new album, for which the seven-song Whatever Happened is simply a calling card. Still, after so long a hiatus, the EP is a joy to hear. I’d wondered if BJ and long-time collaborator, producer Marc Garvey, would shy away from the sound they’d crafted in favor of something more obviously commercial, but instead they’ve dug deeper, returning to the samples-plus-hip-hop-drums core that makes Ghetto Retro feel so warm and timeless.

The single, “Heart & Soul,” captures the throbbing drama of a kind of vintage R&B that concerns matters of deeper import than Bentleys and Belvedere, serving by turns as a declaration of love and an artistic manifesto. Yet BJ also shows off a new swag with an inventive reimagining of 50 Cent’s “21 Questions” over a live band, co-produced by Ledisi mastermind Sundra Manning.

This more than anything else gives a foretaste of the album to come, judging from the unreleased tracks he played me, all of which featured live instrumentation. This is a far more expensive way to make a record, but he hopes to have complete and release it sometime in 2012.

“Honestly, if Tajai hadn’t said, ‘We should do a record, I’ll help you pay for it,’ I probably wouldn’t have been able to do it,” he says, clearly relishing the new material. “I do it for the love of music, nothing else.” *