arts@sfbg.com

HAIRY EYEBALL “Home taping is killing music”, declared the 1980s anti-copyright infringement campaign waged by British music industry trade group, the British Phonographic Industry. History has proven BPI’s concerns to have been mis-targeted, with cassettes becoming an increasingly irrelevant medium in the ensuing decades, even as the music industry still struggles to respond to ever-mercurial forms of bootlegging and pirating. The cassette tape, however, has—perhaps unsurprisingly— re-emerged in recent years as both an object of nostalgia and a more exclusive format for more out-there musicians to release their small, home-made batches of black metal, experimental electronica, or noise out into the world for listeners for whom Tumblr is not enough.

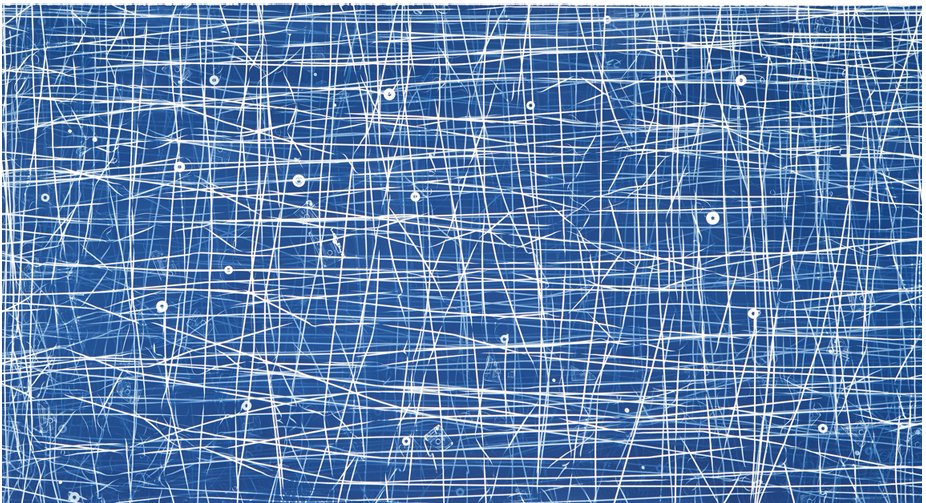

Composer and musician Christian Marclay’s visual art often engages with our complicated relationship to outmoded technologies of audio-visual reproduction, particularly vinyl records. The photograms in his current show at Fraenkel Gallery continues this line of inquiry, playfully condensing the cassette tape’s arc from boon to perceived threat to obsolescence to fetish object.

For the gorgeous 2009 photogram “Allover (Dixie Chicks, Nat King Cole and Others),” Marclay exposed photo-sensitized paper to light after he had strewn over it the magnetic innards of cassette tapes and fragments of the broken plastic shells that once contained them that had been coated in a photosensitive solution. The resulting sprawl of tangled white lines on blue brings to mind the splatter canvases of Jackson Pollock or the chalk squiggles of Cy Twombly (associations Marclay’s titular “allover” winks at). In other photograms, such as “Large Cassette Grid No. 9,” also from 2009, Marclay has arranged plastic cassette cases in block-like patterns that cover the entire paper, with each cases’ accumulated wear and tear providing subtle variations.

That cyan-like blue color is what gives Marclay’s chosen process, the cyanotype, its name. Discovered by English scientist Sir John Herschel in 1842, the cyanotype process was historically used to make blueprints. I’d like to imagine that this irony isn’t lost on Marclay. By using an outmoded photographic technology to make visual art out of an outmoded audio technology, Marclay underscores the eventual obsolescence of all reproductive technologies. His cyanotypes aren’t blueprints so much as headstone rubbings.

In “Looking for Love” (2008), a single channel video shown in the gallery’s backroom, Marclay’s stationary camera stays zoomed-in on a well-worn phonographic stylus, as his giant hands roughly skip the needle around record after record searching for any utterance of the word “love.” The film’s exaggerated scale combined with Marclay’s increasingly impatient and roughshod sample hunting can be read as a parody of the audiophile as techno-purist. But the film also speaks to our enduring investment in music—be it the Dixie Chicks, Nat King Cole, or any of the other inaudible “others” that went into the making of Marclay’s cyanotypes—even as our experience of listening to it becomes more and more immaterial.

HOMETOWN GIRL

Fran Herndon was not a name I was familiar with, so I’m glad to now be acquainted with this largely unsung player in San Francisco’s artistic firmament of the 1950s and 1960s (and all around bad-ass) thanks to the eye-opening selection of early oil paintings and mixed-media collages organized by Kevin Killian and Lee Plested currently on view at Altman Siegel.

An Oklahoma native, Herndon moved to San Francisco in 1957 with her husband, the California teacher and writer Jim Herndon, who she met while traveling in France. She quickly fell in with the likes of the Robin Blaser, Jess and his partner Robert Duncan, and Jack Spicer, with whom she formed an intense intellectual and aesthetic bond. Together, they founded the mimeographed poetry and art magazine J, and Herndon created lithographs for poet Spicer’s 1960 master-work The Heads of the Town Up to the Aether. All the while, Herndon continued to produce her own varied body of work that was as much a response to her newfound creative circle of friends and collaborators as it was to the times in which they were making art.

The series of sports themed collages she made in 1962 are especially representative of Herndon’s gift for exploding the hidden currents of emotion contained in her source material—in this case, images clipped from popular magazines such as Sports Illustrated and Life are transformed into near-mythological tableaux of victory and defeat in which race and the volatile racial climate of Civil Rights era-America are front and center (Herndon, who is of Native American heritage, has said “[America] is no place for a brown face”).

In “Collage for Willie Mays” the baseball legend is depicted hitting a homer out of a Grecian colonnade whereas in the decidedly darker and Romare Bearden-esque “King Football” an actual mask has fallen away from the titular ruler, revealing a skull-like visage wrapped in a cloak of newspaper clippings about the 49er’s then-scandalous decision to trade quarterback Y.A. Tittle for Lou Cordilione. The headlines about devastation and death speak to other off-field losses, though.

Other pieces resonate on a more emotional level. The gauche-smudged greyhounds in “Catch Me If You Can” bound past their bucolic counterparts like horses in a Chinese brush painting—all speed and wind—and are as much signs-of-the-times as the more politically overt anti-draft and anti-war collages Herndon made later in the decade.

Certainly, there was no time to wait. So much of Herndon’s art seems to come from an urge to document her “now” with whatever tools she had on hand, a present being lived and produced in the company of so many extraordinary others, from Spicer to Mays. Even her paintings seem to have been worked on only to the point at which their subjects just emerge distinct from their swirled backgrounds of color. Nearly fifty years later, Herndon’s urgency is still palpable.

CHRISTIAN MARCLAY: CYANOTYPES

Through Oct. 29

Fraenkel Gallery

49 Geary, Fourth Floor

(415) 981-2661

FRAN HERNDON

Through Oct. 29

Altman Siegel Gallery

49 Geary, Fourth Floor

(415) 576-9300