arts@sfbg.com

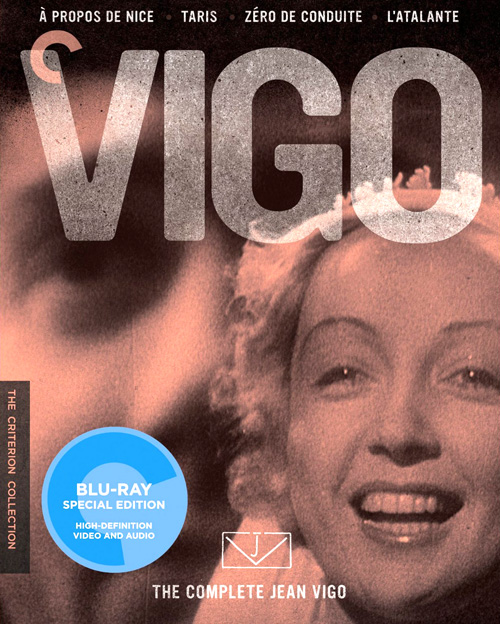

FILM The beatification of Jean Vigo as cinema’s Romantic poet — only four films before tuberculosis carried him off at 29 — is one of the less interesting things about him. As myth it’s maudlin and a little corny, nothing like his films which won’t sit still long enough for you to call them immortal. Whether structured as an exploded city symphony (1930’s À Propos de Nice), commissioned portrait (1931’s Taris), anarchic boarding school farce (1933’s Zéro de Conduite) or multivalent love story (1934’s L’Atalante), they crack open the known world and flash epiphanies like jewels before the camera.

Vigo’s most famous sequences — the pillow-fight processional in Zéro de Conduite, the lovers’ séance in L’Atalante — are lyrical outbursts expressing deep yearning. That desire can be sensual or social; the toppling effect is the same. One might take a page from Vigo’s first film, À Propos de Nice (co-directed with Boris Kaufman, Dziga Vertov’s brother and a brilliant cinematographer in his own right), and consider the intense flux of Vigo’s films as pushing towards carnival. The film’s witty comparison of the idle rich and vibrant working class of Nice goes up in smoke with the fade-in to the street fair. The social fabric suddenly tears, egged on by lusty low-angle shots and intoxicating cuts (more than that, Vigo himself appears doing the cancan).

In Vigo’s little-seen short Taris, the titular French swimmer and early media celebrity demonstrates strokes while explaining their form in voice-over. This instructive track is periodically interrupted by the filmmaker’s beautiful (and at times absurd) close-ups and slow-motion shots. In the end the libidinal again wins out, as Vigo takes advantage of a portal window to film Taris underwater turning corkscrews and circles. This sweet celebration of the body is recast as the more famous underwater idyll in L’Atalante, but here seeing Taris at play here provides a striking contrast from his more regimented athleticism. Stepping outside the rules of the sport, he doesn’t even need to come up for air.

Plenty of ink has already been spilled on Zéro de Conduite‘s joyful student revolt, though I’ve always appreciated that when the emboldened kids hail garbage down on the authorities of church and state, some of the figures below are actual puppets. Even when Vigo’s films are deadly serious, they don’t take themselves too seriously. The censors certainly did: the film was banned for its many blasphemies, though it surfaced sooner than the long shipwrecked L’Atalante. The story of a married couple coming together and apart on a barge is simplicity itself, and yet Vigo embroiders it with delicate shifts in mood and setting. The carnival spirit is here embodied by indelible Père Jules (Michel Simon), the salty sailor who whether playing a record with his finger, trying on a dress, clutching a litter of kittens or showing off his tattoos generates a turbulent vitality that’s a full partner in the film’s romance. L’Atalante is a giving film, with a musical sense of character, a wondrous balancing of melancholy and mischief, and always something new to tell you about love.

There are some who might grumble about the obvious irony of seeing Vigo’s freewheeling work packaged as a tidy commodity, but it’s humbling to think what earlier generations of film lovers would have made at being able to stuff his collected works in their coat pockets (also, Criterion’s transfers are stellar). It’s marvelous being able to explore these particular films at leisure — which is to say every which way. You see all the explosions of fantasy into real life and vice versa, and you think how unusual for someone to seek freedom not only in but through cinema.