arts@sfbg.com

FILM It’s grown obvious in ways it couldn’t have been originally that from 1970 to 1980 Nicolas Roeg was the most adventuresome English director, even if then as now his work seems less “British” than just about any colleague you could name. Perhaps not quite knowing where he was coming from — in any sense — made Performance (1970), Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), and Bad Timing (1980) messy, strange, and interesting in ways that then felt borderline gimmicky, as disjointed as they were deliberately dislocative. Yet all those qualities have helped the films age beautifully. In fact they’ve scarcely dated at all, perhaps because their lateral rather than linear storytelling, seemingly contrary audio and visual cues, and pervasive cultural unease reflect a mindset familiar enough now but very strange those decades ago.

That remarkable run comes to mind because of Earth‘s return in a newly struck 35th anniversary print that offers the complete 139-minute “director’s cut.” That version has in fact been available for years — the heavily-cut original U.S. theatrical release is doubtless harder to find now — but remains full of surprises. Even after so long a span, it’s a science fiction movie unconventional enough to annoy the hell out of many professed sci-fi film fans. But then their template was formed the next year by Star Wars (1977), then shortly thereafter by Alien (1979) — two expressions of sci-fi rooted in comic books and ’50s monster movies respectively, spawning innumerable imitations since equally focused on action over ideas.

The Man Who Fell to Earth, stubbornly, has no interest in spaceships, let alone battles or creatures. Instead, its subject is human society, which from the title character’s viewpoint really is nothing for our planet to brag about. It’s still an alien piece of filmmaking because Roeg wants us to view earthly life with fresh eyes that gradually dim from amused curiosity to the cynicism of a reluctant émigré forced into permanent residency in a land he despises.

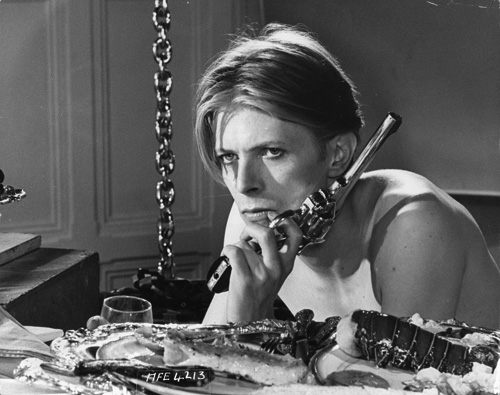

In his first major film role, David Bowie plays Thomas Newton, who turns up in the American Southwest out of the blue — no one realizes at first quite how literally — with ideas for “toys” of extraordinary technological advancement that quickly make him a very, very wealthy man. Amassing money seems to be his only real interest, toward a goal he eventually reveals to hand-picked confederates including patent attorney Buck Henry and technician Rip Torn, plus singularly dim companion Mary-Lou (Candy Clark). That goal is constructing a space vehicle capable of returning Newton to his planet, which is dying from drought. (Our protagonist’s decline is charted in his changing beverage choices, from precious water to the cheap consolation of alcohol.) He intends no harm. But despite all efforts at evading notice, he inevitably attracts invasive government attention as a freak of potential scientific, capitalist, or militaristic use.

Taking considerable liberties with Walter Tevis’ novel, Paul Mayerberg’s screenplay and Roeg’s direction enlarge several subsidiary characters, add a number of new incidents, and minimize Newton’s backstory. Yet when Earth was first released in the U.S., its 20-minutes-shorter edit removed much of the more outré inventions — including a whole lotta sex scenes, mostly between college prof Torn and myriad female students — oddly re-asserting the story’s science-fiction emphasis. Yet what remains fascinating about the film, beyond Bowie’s silvery performance and Roeg’s arresting stylistic strategies, is that it’s every bit as much a stunned observation of mid-decade middlebrow Americana as the same year’s Nashville. Like a Tibetan monk transplanted to a papier-mâché dinosaur theme park, Newton is agog at a vigorous garishness that’s as invasive as the probes eventually stuck into his body. Chocolate chip cookies, evangelical hysteria, Elvis musicals, and Mary-Lou’s ever-changing hairdos are all an equal amazement to him. The people around him age decades, but he never does, and strangely neither does the culture; when Clark and Torn visit a record store in their twilight years, it’s still selling Jim Croce records to Me Decade longhairs. Newton’s tragic fate is to be trapped in a space-time warp of alien triviality.

Famously crossing over to direction from cinematography (on movies like 1967’s Far From the Madding Crowd and 1968’s Petulia), Roeg brought a sensibility to his own projects that owed less to film and theater than to modern still photography, experimental cinema, and the literary avant-garde. Before anyone else thought likewise, his soundtracks felt like wildly unpredictable (but apt) mix tapes.

None of his features strictly fit any genre they’re aligned to, when there is one. Don’t Look Now is less interested in the supernatural than the psychological deterioration of a marriage. Bad Timing is still under appreciated as the decade’s more disturbing follow-up to Last Tango in Paris (1972), wherein male control of the female sex object grows increasingly desperate and destructive. Performance, co-directed with the late Donald Cammell, was supposed to be a Swinging London snapshot a la Blow-Up (1966) — fashionable, arty, a little kinky, with Mick Jagger acting as lure. It turned out such a druggy, gender-bending mindfuck that Warner Bros. initially refused to release it. A processing lab destroyed some “obscene” footage without permission; even without that, audiences walked out, demanded refunds, even vomited. Performance no longer shocks, but it’s still subversive.

After 1980, Roeg’s output grew steadily less compelling. After years of silence suddenly there was 2007’s Puffball: The Devil’s Eyeball, a seriocomic semi-fantasy curio based on a Fay Weldon novel. No one saw it; they didn’t miss much. At 82, it’s quite possible Roeg won’t make another feature. Yet that single decade of remarkable work still points forward, and has influenced many of the more interesting younger directors’ approaches to style and storytelling since.

THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH opens Fri/9 in Bay Area theaters.