Five minutes into talking with Amanda Curreri over a slice and coffee at Mission Pie, I’ve agreed to take part in a piece she’s working on as part of Shadowshop, the in-gallery artists’ marketplace Stephanie Syjuco is organizing for SFMOMA’s upcoming survey of work made in the past decade.

“It’s called Afghanistan Insert,” Curreri explains, speaking in the measured fashion of someone who carefully considers her words. “I’m trying to insert Afghanistan into SFMOMA and into San Francisco’s art community.”

Curreri’s commitment to getting the local arts scene to engage with what has become commonly dubbed by the mainstream news media as “the forgotten war” is not just politically motivated. It’s also personal. Her husband has been working in Afghanistan for the past five months as a security contractor, during which he has sent her snapshots of local graffiti. They are documents of his ground truth.

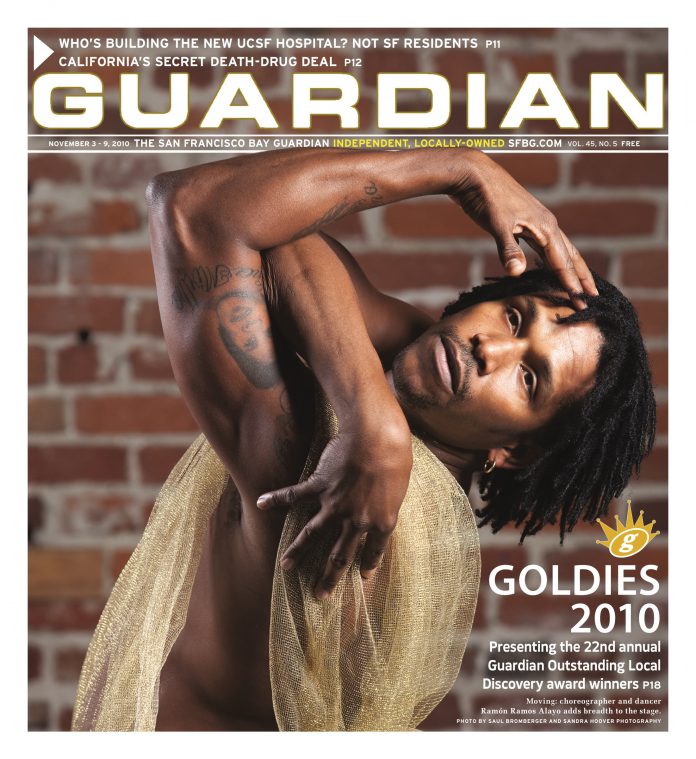

Curreri plans on physically inserting herself and her husband’s images into Shadowshop, much in the same way she holds one of his pictures in the portrait accompanying this feature. Indeed, the photo, this profile, Curreri’s new status within the local arts community as a Goldie winner, and the conversations this increased attention might encourage will all become part of the discourse surrounding Insert Afghanistan and contributing to its impact.

All this is consonant with Curreri’s view of herself as more of an instigator than an artist. “I’m trying to make art that crosses out of the art world,” she says, echoing Joseph Beuys’ notion of social sculpture. Her projects thrive on participation, using the exhibition space as a kind of social laboratory in which she arranges shared cultural touchstones and institutions — campfire songs, the judicial process, family recipes — as prompts for personal reflection and shared conversation on the “big subjects” that undergird them: history, politics, memory, and in the case of Afghanistan Insert, their intersection within a seemingly endless and fruitless foreign occupation thousands of miles away.

Engaging with Curreri’s art often entails an extended encounter with the artist herself (given how unexpectedly my interview at Mission Pie has turned out, the reverse seems true as well). The last conversation I had with Curreri was this past July, when she videotaped my extemporaneous responses to her off-camera questioning about the topic of last words. My interview was to be incorporated into her concurrent exhibit “Occupy the Empty,” for which she transformed Ping Pong Gallery via hand-sculpted “props” into a courtroom in which various associates, friends, and strangers, such as myself, volunteered their time and testimony.

As with Insert Afghanistan, the inspiration for “Occupy the Empty” was also personal: after participating in a court hearing concerning her late father, Curreri found out it had been held in the same Massachusetts courthouse in which Italian-American anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti were sentenced to death in the early 20th century. Curreri, also of Italian-American descent, saw the coincidence as a chance to connect to that history and, in the process, build a community around a larger discussion of remembrance. Curreri recalls one participant for whom the show served an almost therapeutic function.

“I want to create art that has an interpersonal function, in real-time,” she says. “I want my work to set a specific frame around our inherent connectivity.”